It’s been 125 years. More than ever, Van Alen Institute’s legacy as a center for design innovation, bridging architectural education and professional practice, is pivotal to the Institute’s future as we investigate the most pressing social, cultural, and ecological challenges of tomorrow on a global scale.

Over a dozen decades, the organization has served the public under diverse titles, culminating in our 21st-century mission that design can transform cities, landscapes, and regions to improve people’s lives. Let’s explore how Van Alen’s past set the stage for its present-day cross disciplinary research, provocative public programs, and inventive design competitions.

Beaux-Arts

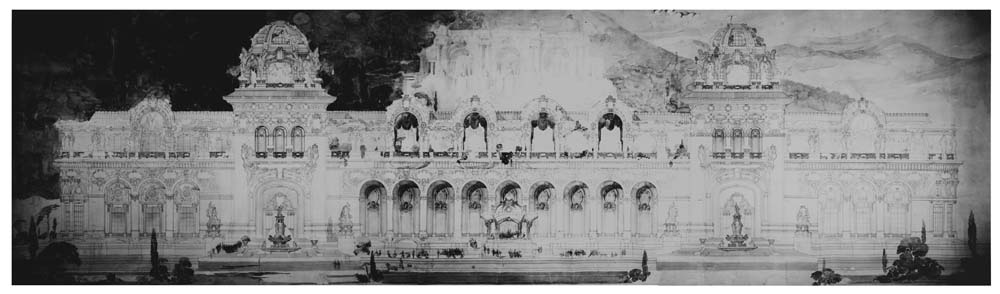

The organization’s first iteration at the end of the 19th century was informed by the prevailing architectural movement of the time, Beaux-Arts. This Neoclassical strain was rooted in its namesake educational institution, Paris’s Ecole des Beaux-Arts. But that the movement was so closely knit to the Continent left some aspiring American architects out of the loop.

To close the knowledge gap, a brigade of Ecole des Beaux-Arts alumni banded together in 1894 to found the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects, dedicated to establishing a rigorous and highly competitive atelier-based architectural curriculum modeled after its French counterpart. The founding objective of the Society was to cultivate, perpetuate, and test the teachings of the original Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Central to this pedagogy was study of Greek models and Imperial Roman architecture, polished perspective drawings, and careful consideration of the urban public.

Available free of charge to any student admitted, the design ateliers proved enormously influential. While maintaining the Ecole’s design standards, the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects broke down the hierarchy and culture of exclusivity that previously defined the scholars who made it across the pond – architectural education was suddenly accessible.

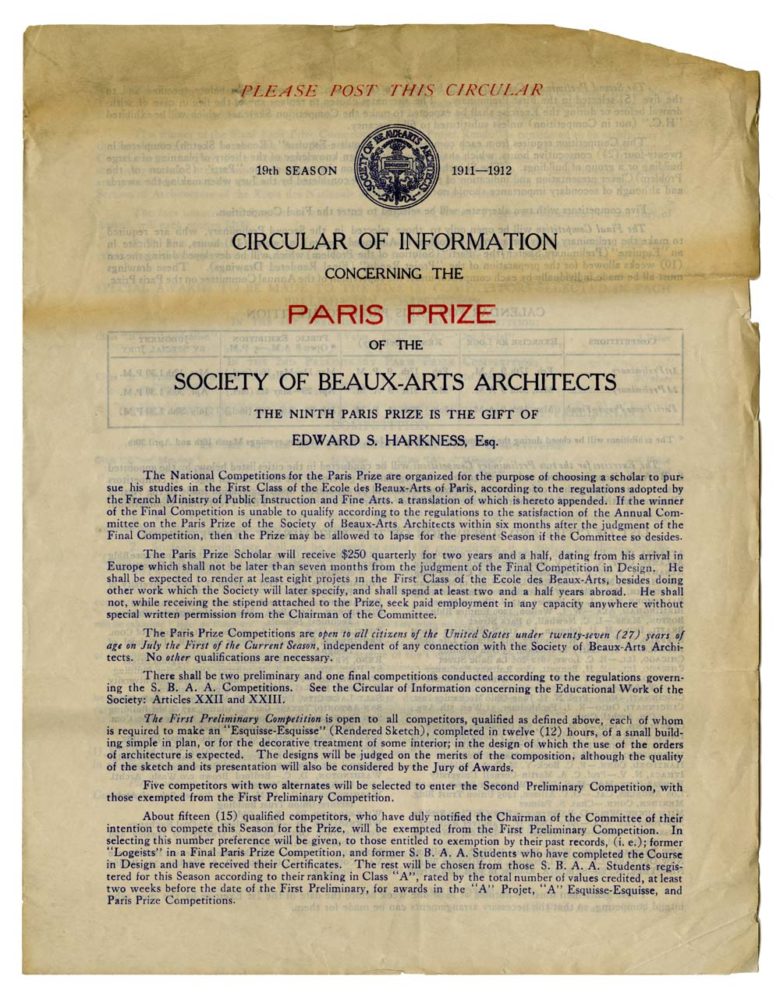

Courses revolved around a series of increasingly demanding competitions and design challenges, culminating in the Society’s nationally recognized Paris Prize in Architecture, which sponsored study at the Ecole for its annual recipient. The Paris Prize acted as a harbinger of the design competition serving as a vital educational tool for American architecture students.

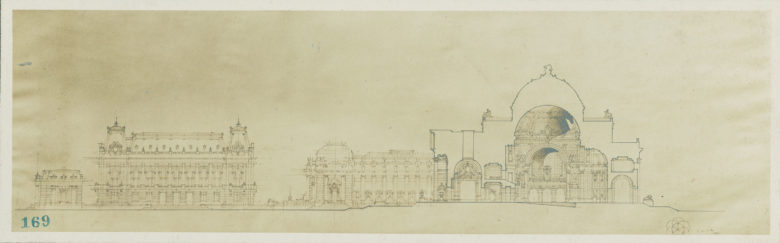

In 1908, a 25-year-old Williamsburg, Brooklyn-born upstart architect was awarded the Paris Prize in a competition for the design of a theater. The recipient was William Van Alen, and his application was backed by a thorough design pedigree.

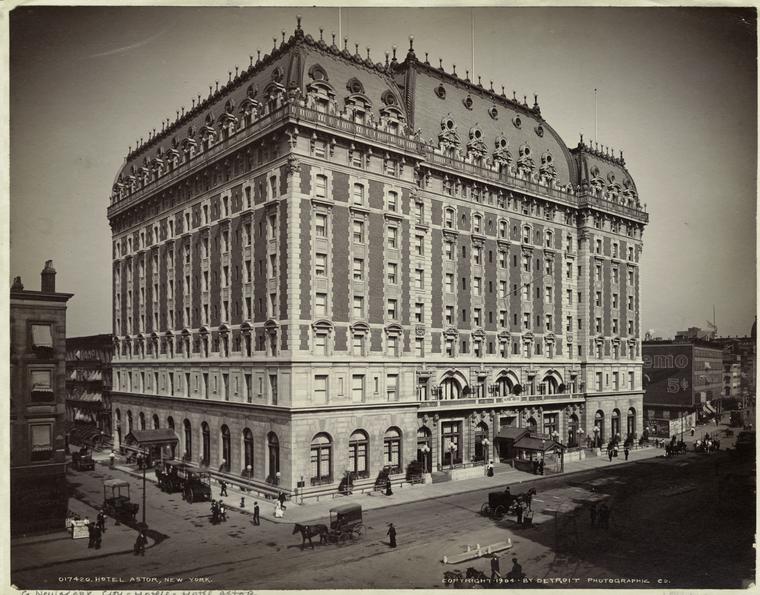

Prior to winning the Prize, Van Alen had already worked in the studio of Clarence True while a student at Pratt Institute. His professional life before studying at the Ecole was also defined by three years in the atelier of French émigré architect, Emmanuel Louis Masqueray. And at the firm of Clinton & Russell, he worked as a draftsman on the Hotel Astor — a green mansard roofed Beaux Arts jewel on the intersection of Broadway and Seventh Avenue, which would soon be renamed Times Square.

Once in Paris under the auspices of the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects, the young Van Alen was exposed to applications of elaborate ornamentation upon innovative cast-iron frames in the atelier of Victor Laloux. The soaring glass roofs that this technology allowed are evident in Laloux’s trademark structure, the Gare d’Orsay (now the Musée d’Orsay) and would later appear in Van Alen’s commissions.

The international dialogue and appreciation of innovative civic space that Van Alen gleaned at the Ecole would become trademarks of the organization that would eventually bear his name.

When Van Alen returned to New York in 1910 and set up shop with H. Craig Severance at the Metropolitan Life Tower at 24th Street and Madison Avenue, he found the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects flourishing as never before. By 1912, an independent network of over 100 Society of Beaux-Arts Architects ateliers thrived throughout the United States, where thousands of students and young professionals annually received courses of architectural instruction from established American architects.

As professional education in America shifted from the atelier system to colleges and universities, the Paris Prize and its affiliated fellowships continued to engage students in architecture programs across the country. The Society grew as a social organization promoting comradery among designers.

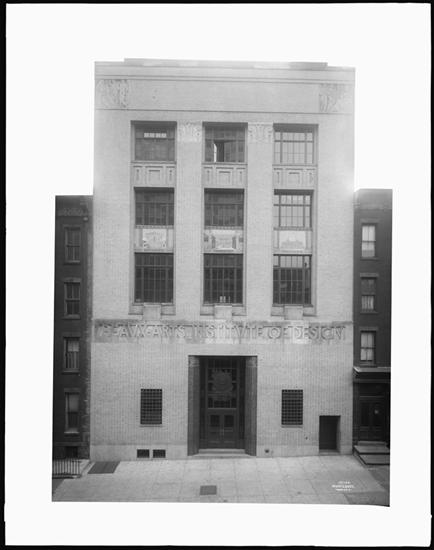

In 1916, the Society expanded from a club of ateliers to an interdisciplinary, degree-granting institution. The newly chartered Beaux-Arts Institute of Design was founded in cooperation with the National Sculpture Society and Society of Mural Painters. The Beaux-Arts Institute of Design became the overseer of many competitions as well as a breeding ground for skilled first-generation Americans in the building trades.

1920S

The graduates of the Society’s earlier ateliers prospered in a heightened economic climate. Designers eschewed cornices and masonry for sheer glass facades, brash cantilevers, and ever-higher stories. In 1928, Van Alen was hired for his most recognizable commission — the Chrysler Building, briefly the world’s tallest building.

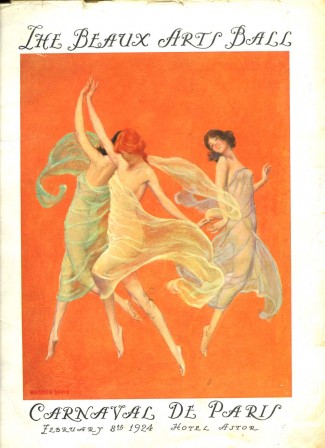

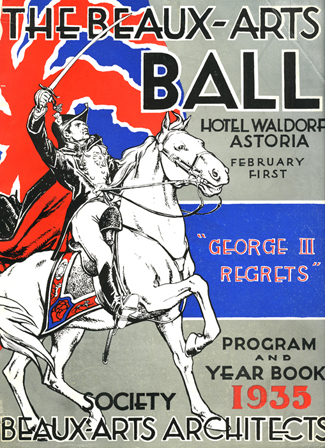

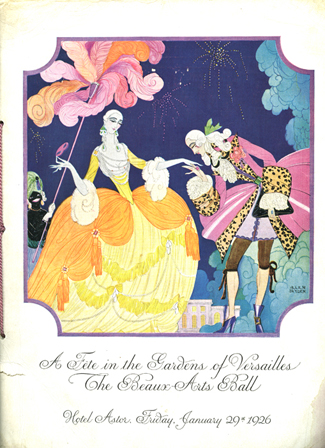

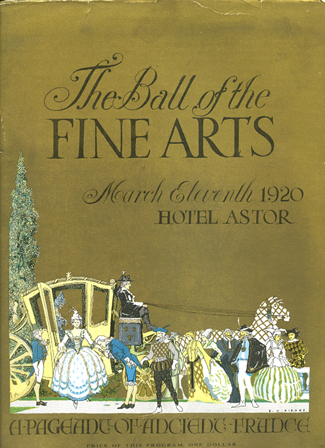

In keeping with the spirit of the roaring 20s, the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects threw an annual ball, as the students of the Ecole des Beaux Arts had in Paris that served as the key fundraiser for the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design’s educational programs and activities. The balls involved elaborate costumes and performances covered extensively by The New York Times society pages.

MIDCENTURY

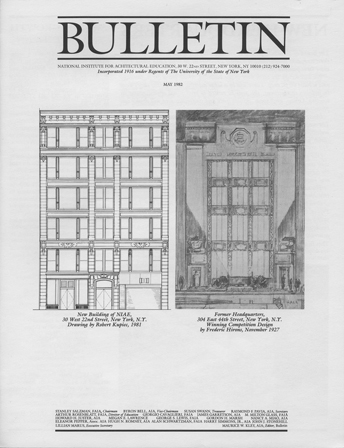

The Society of Beaux-Arts Architects remained in existence as a social organization and overseer of the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design until dissolution in 1942. By then, the grandiose flourishes of the Beaux-Arts style were passé and schools leaned towards the Bauhaus and International Style. The Institute shed its Francophile cloak in 1956 and was renamed as the National Institute for Architectural Education (NIAE).

In a new spirit of openness, the NIAE was unaffiliated with specific design movements in order to elicit the most imaginative design work from the students and young architects across the United States who applied to the Institute’s competitions and fellowships.

Through a broad program of educational activities and an expanded awards program, including the Van Alen Memorial Prize and the Dinkeloo Fellowship at the American Academy in Rome, the Institute functioned as a critical resource and facilitator to formal architectural education.

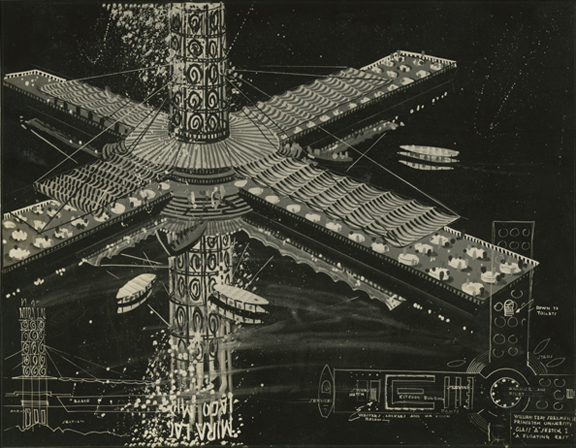

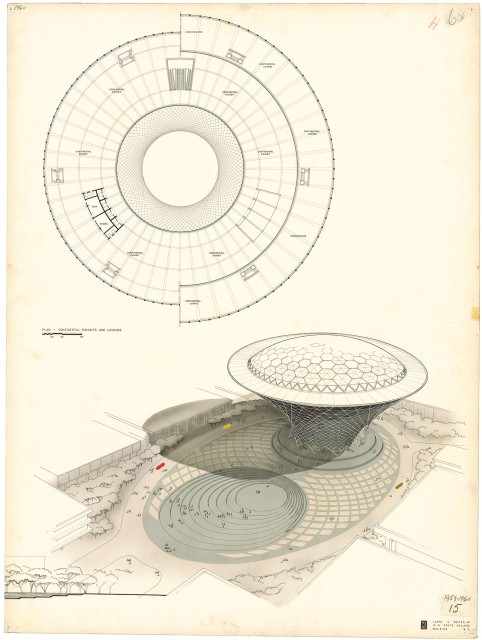

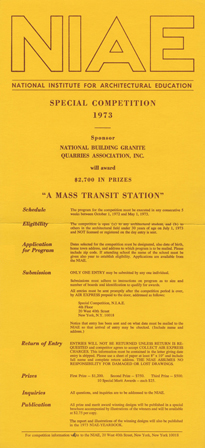

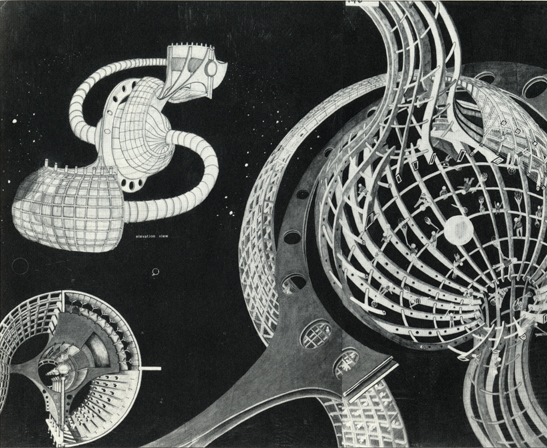

For the next four decades, the National Institute for Architectural Education (NIAE) hosted a wide spectrum of design challenges and projects, reflecting the modernist expansion of civic space as an architectural domain unfettered by the monumental public building.

1990s & 00s

In 1995, the NIAE was renamed in honor of Van Alen, who was survived by his wife Elizabeth following his death in 1954. The widow bequeathed half of the architect’s estate to the organization upon her death in 1970. The new Van Alen Institute assumed a more public, political role in the shaping of the public realm, while continuing to cultivate a network of practitioners and scholars and award excellence in design.

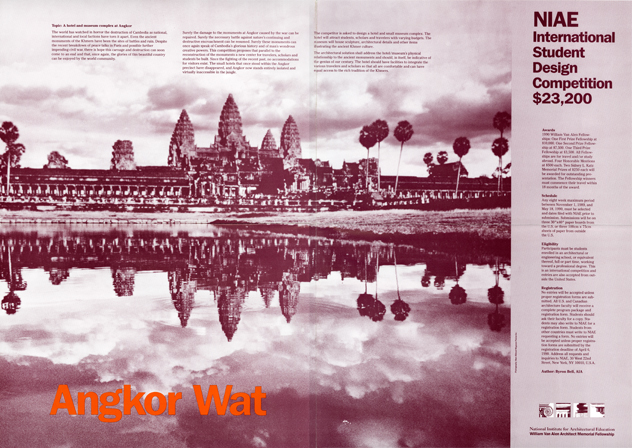

The Institute entered the 21st century probing sites stretching from Taos and Toronto to Angkor Wat with innovative competitions. Local programs re-imagined critical New York City sites like Governors Island, sparking conversations that catalyzed the thriving public space that has evolved from a former federal military base, and the spectacular junction of Times Square, resulting in the construction of a new TKTS booth with a public roof made iconic by its vibrant red steps. On the sixth floor of Van Alen’s current Flatiron District location, exhibitions were mounted exploring the intersection of public space and recreation, urban air quality, and reimagining the landscape of Lower Manhattan after 9/11.

2010s

Van Alen Books, designed by LOT-EK and supported by Furthermore, a program of the J.M. Kaplan Fund, opened in 2011 as a temporary pop-up store gathering place devoted singularly to architecture and design publications. For three years, the initiative acted as a platform for debate of timely issues in the wake of international economic and environmental upheaval. The range of book launches and panels brought together audiences of architecture students and young professionals looking to share ideas and test new ways of thinking about design.

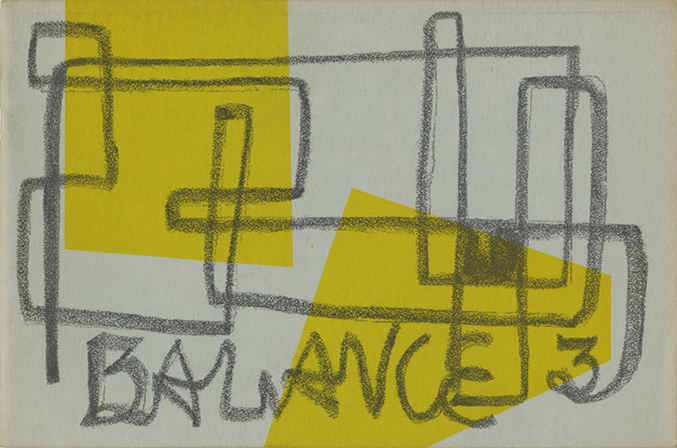

A competition to further activate the street level of our Flatiron District site was launched in 2013, resulting in the opening in 2014 of a new space designed by Collective-LOK, a collaboration of Jon Lott (PARA-Project), William O’Brien Jr. (WOJR), and Michael Kubo (over,under). The joint program hub, gallery, and workspace is poised to facilitate the realization of Van Alen Institute’s mission as we continue to leverage design to rigorously investigate the most pressing social, cultural, and ecological challenges.