As part of our recent program series, HANGOUTS!, Van Alen and UnionDocs organized a roaming celebration of local experiences across the barrio of Los Sures. Here, Isabella Brandalise visits the studio of Tamara Gayer, one of the participants in Living Los Sures, to gain insight on how the visual elements of our local environments impact our daily lives:

Tamara Gayer defines herself as an artist transfixed by the city. “The city is my natural habitat,” she declares as a subway train roars along the J/M tracks just outside her South Williamsburg studio, which is populated with colorful pieces of art, rolls of vinyl, cutting tools, and compu

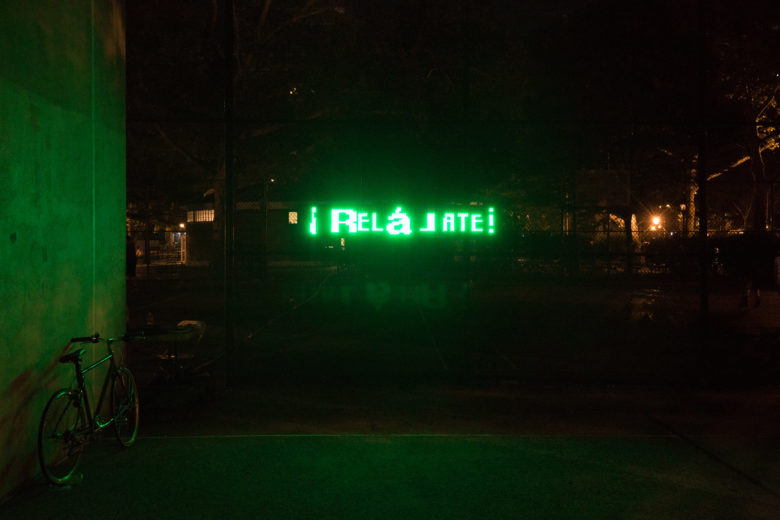

As part of Van Alen Institute’s recent Brooklyn Barrio: Living Los Sures day-long event, the artist debuted This is the Southside, a site-specific piece in the southern section of Williamsburg. Collaborating with local businesses, Gayer asked shop owners to add a specific message to the LED advertising signs that adorn their storefronts windows.

Visitors and residents making their way through the neighborhood can find a pattern in the messages, and trace a genuine portrait of the Southside, as they walk from sign to sign.

The collection of shop sign interventions was bookended by two of Gayer’s own LED signs, one at Sternberg Park and another at UnionDocs (a 10-minute walk from each other), which compiled the various messages alongside phrases developed by the artist.

This is the Southside has a particularly intimate connection to Gayer’s daily life, as she explains, “My studio is so close [to the area] and I’ve lived in South Williamsburg for 20 years plus, so I felt like it was something I knew about.” Her creative process, a dialogue between abstract concepts and concrete materializations, retains inspiration for the latter from the specific location of each project. Gayer notes, “There is always at least something which is in the immediate vicinity, and that speaks very particularly to the people who are really from that area.” By collaborating with the bodegas, laundromats, and family-owned stores in the neighborhood, places which local residents activate as ad hoc hangouts, she revealed the graphic and aesthetic elements of their signs—qualities that are often concealed because of their messages of advertising: “Coffee 99 ¢”, “WE HAVE CIGARETTES,” and so on.

Gayer is immersed in the notion that we are surrounded by advertising: “That’s just how we live. That’s totally fascinating and actually really great and eye-opening in many ways.” Her projects provide a new format in which the advertising message remains, but removed from its original setting, it communicates something completely different, something not at all related to selling. In the Southside piece, the result is an analogous poetic process of researching and capturing what hangouts mean to different people, expressed in the neighborhood’s Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican and Dominican communities’ own words. For the project’s second location, at UnionDocs, she concentrated on concepts surrounding money and economic disparities, reflecting on the situation between the old and the new Williamsburg, regardless of ethnicities. By repurposing and combining elements of advertising, a practice Gayer has explored across the past five years, she conveys the unseen potential of these technologies and aesthetics.

With her vibrant street-level installations, Gayer intends to liberate a space to think about where we live, and how we use and inhabit our neighborhoods and surroundings. She wants to create a poetic deautomatization of everyday lives, allowing for possibilities instead of trying to dictate what one should think or feel.

“People do respond, ‘Oh, we looked at our area totally differently,’ ‘We saw our buildings, but then we saw something they could be, other options,’” she says. In response to the Southside project, an artist contacted Gayer to tell her how the work made him change the way he sees technology on the street. Other spectators were skeptical, as Gayer recounts, “A lot of people came and they would say: ‘This is great, it’s beautiful, but what are you selling me? What is your brand?’ Over and over.”

In addition to advertising, Gayer draws inspiration from her personal migrations. Born in New York City, Gayer spent her early years in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Tel Aviv, a reflection of 20th-century Israel, is a city with a relatively new physical presence, “a product of Bauhaus-trained architects who fled Europe before and during World War II,” very much in contrast with the ancient element of Jerusalem. Now she has been living in New York City for over 20 years, and often takes the city as her subject. Less about form and more about subject matters, Gayer’s work had a relevant influence from the outpouring in 1990s New York City of art, which raised issues of identity, politics, and inclusion—ideas Gayer explores as she navigates the public realm.

Adopting the street as her platform, the artist transits ambiguous intersections of art, architecture, and design. Gayer, however, is clear about her position in the fine arts field, and the liberty it entails. “In architecture and design there is always a client, there are always a lot of rules,” says Gayer, who prefers the notion of personal will that comes with an art project. “That very happily gives me the room to play,” she says. For Gayer, play is a revolutionary idea that sets the groundwork for free interpretation that reappears in This is the Southside, as she leaves the project open-ended. “Play is not trivial,” she says, “because it is where the openness exists, for people to form their own conclusions.”