Future Ground was a design competition that invited multidisciplinary teams to generate flexible design and policy strategies to reuse vacant land in New Orleans, transforming abandoned landscapes into resources for the current and future city.

Across the world, cities have conquered the vacant lot. The proof is in countless urban farms and stormwater gardens and other open spaces that have thrived in the wake of a demolished structure. But figuring out what to do with vacant land – the unwieldy sum of hundreds or thousands of small, scattered lots – has proven much more difficult. We organized the interdisciplinary design competition Future Ground to bridge this gap, helping the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority (NORA) and its counterparts in cities around the country to rethink vacant land reuse beyond the single lot and to scale up initiatives to have larger, citywide impacts.

Over the course of six months in 2015, the three winning multidisciplinary design teams – NOLEX, PaD, and STOSS – tackled fundamental questions not only about vacant land, but also about creating more equitable cities: How can we build unconventional partnerships to improve quality of life in underserved communities? How can land support businesses that create living wage jobs for residents without college degrees? What future opportunities will exist in neighborhoods with low market demand? The teams’ approaches to job creation, community engagement, and planning for low-density neighborhoods are now informing NORA’s and the City of New Orleans’ plans to create a more equitable, resilient city. We are deeply grateful for the work of the three teams that participated in the competition, and for the tireless efforts of so many others around the city and the country who have shared their expertise with us over the last six months.

Van Alen Institute has synthesized below the six most compelling elements from the teams’ proposals for optimizing vacant land reuse in New Orleans and in American cities struggling with similar issues. View the entire illustrated report.

VACANT LAND CAN HELP CITIES CREATE JOBS

Vacant land is intertwined with unemployment, income inequality, and other economic problems; it can also be a foundation for economic growth. For instance, cities can offer land to recruit or support businesses that typically create living wage jobs. But in order to make vacant land a catalytic part of an economic development and jobs strategy, cities need to assemble smaller lots into large parcels.

Economist Teresa Lynch and the Team Stoss found that certain types of land (2 – 4 acre parcels zoned for light industrial, distribution, and repair activities) are critical for supporting industries that create living wage jobs for workers without college degrees, and that many of these industries could grow in New Orleans if land were available. Publicly owned vacant land could be a key resource in helping these types of activities locate in the city, but the vast majority of New Orleans’ vacant land consists of thousands of former residential lots, usually around a tenth of an acre – a common condition in cities around the country dealing with widespread abandonment.

Agencies prioritizing job creation as an outcome of vacant land reuse should explore strategies for assembling smaller parcels into larger sites. But this is only a first step – agencies will still have to rezone abandoned residential lots to allow new businesses to operate there. Making sure that land assets support broad-based prosperity is a critical first step in a comprehensive and coordinated economic development strategy.

KNOW WHEN TO HOLD ‘EM

Generally, city agencies try to get vacant lots in other people’s hands as quickly as possible through auctions, partnerships with affordable housing developers, side lot sales, and other methods. This isn’t always an optimal strategy – once these lots are sold, cities are still left with others they can’t sell and have lost the opportunity to bind parcels together to make land available for larger impact.

Cities should suspend single-lot auctions in some areas or for certain clusters of vacant land to achieve larger ecological, economic, and social benefits. It’s not easy to convince mayors that instead of getting vacant lots off the city’s books and earning money from auctions, they should invest in acquisition and other strategies to create larger parcels of land. Especially in cities with huge inventories of vacant land, a targeted acquisition strategy, in combination with tools such as auctions, must be part of the policy toolkit. In some areas of the city, we need a new sense of scale – not only thinking beyond the single lot but also beyond short-term gains, to 5, 10, or 25 year horizons, and the kind of strategic planning this longer timeframe allows.

ENGAGE STAKEHOLDERS THROUGH MUTUAL INTERESTS

What do a public health official, an urban wildlife advocate, and a city official in charge of stormwater management have in common? None of them consider vacant land reuse part of their core mission. But chances are they want something that vacant land could help provide – they just don’t know it yet. By focusing not on the land itself, but on what various groups could use land for, cities can enlist a lot of new partners to join the effort to reuse vacant land.

Team NOLEX proposed a simple model for agencies such as NORA to take an active role as a matchmaker:

Step 1 Reach out to many unlikely suspects (e.g. bike advocates, arts organizations, and disaster preparedness groups) and identify what these stakeholders’ priorities are (e.g. low-cost, visible places for events or safe, active urban corridors).

Step 2 Using readily available data on residents’ health, soil quality, elevation and many other conditions, locate specific areas of the city and clusters of vacant lots that could serve stakeholders’ needs – and see where these groups’ needs overlap.

Step 3 Bring these groups together, showing them how they could use city-owned vacant land to address common interests.

The team’s proposal would require that cities dedicate staff and resources to a new form of outreach. But this investment could greatly expand the pool of stakeholders who can lend a hand in vacant land reuse, bringing in new ideas and resources.

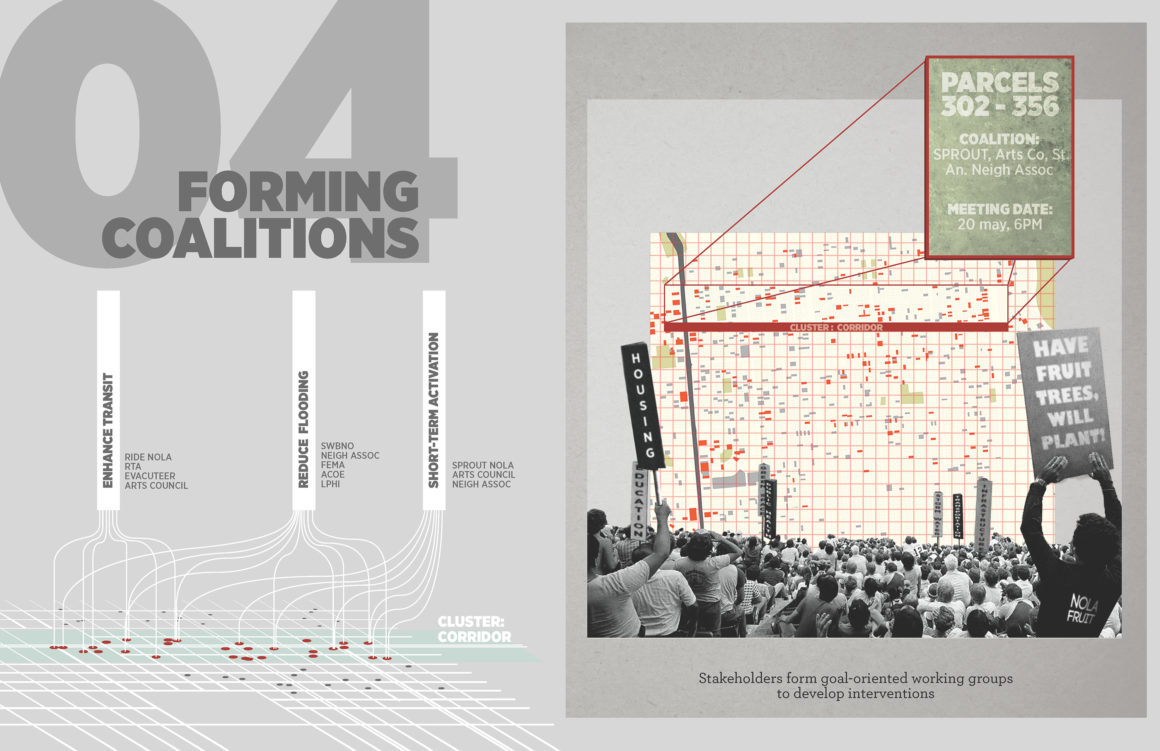

LET THE PUBLIC GET CREATIVE

Community engagement processes often look the same no matter where you go – they take place toward the end of a project, and ask the public to provide feedback to proposals using post-it notes and large maps. It’s time to reinvent conventional models for engagement by making them more, well, engaging, and by integrating the processes into decision-making and evaluation processes.

Through a pilot engagement process, Team NOLEX brought together a broad range of real world stakeholders to role play in a negotiation around a vacant lot: for example, a city official took the role of a wildlife conservationist who wanted to establish butterfly habitat, while a public health expert acted as community association president trying to pave the lot over. The “game” helped people build new, unexpected coalitions, and to learn about technical issues in a fun way.

Team Stoss recommended that NORA and other agencies use engagement as an opportunity to rethink how they develop projects, programs, and policy. For example, when starting work in a given neighborhood, agencies could engage community leaders to identify the best ways to reach the broadest cross-section of people living in the area, rather than use the usual, one-size-fits all approaches. These examples demonstrate ways that engagement initiatives don’t have to be a final hurdle to getting to a built project. When the process is more creative and collaborative, the results will be too.

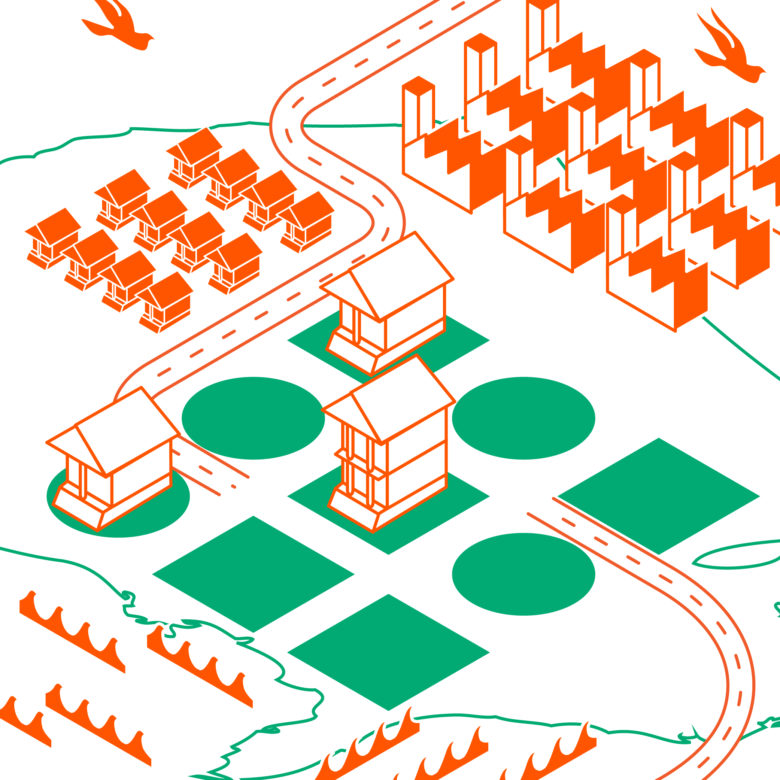

LOOK AT VACANT LAND AT A REGIONAL SCALE

We’re used to thinking about vacant land at a city scale: it’s Cleveland’s problem, or St. Louis’, or Detroit’s. To open up new possibilities for vacant land, cities need to look beyond their borders. At the regional scale, a neighborhood’s vacant lots fit into a bigger picture of investment and organizing around roads, wildlife areas, waterways, and tourism.

Vacant land is part of a regional system, existing within and connecting to regional economies, highways, rivers, and wildlife areas. Team PaD examined the Lower Ninth Ward not only as a neighborhood in New Orleans, but as a storm water management zone and urban habitat that could be scaled up regionally via cross-parish collaboration. This framework places the neighborhood in the context of state parks and other natural resources within a 50-mile radius, as well as a host of potential partners pursuing federal ecological restoration efforts and planning for eco-tourism in the region.

CREATE NEW VISIONS FOR LOW DENSITY

Too often, vacant land has been seen only as a remnant of what used to be. But both the people who have stayed and those who have recently arrived in these neighborhoods are creating a new kind of city – one with far fewer buildings and businesses than before, and much more space, trees, and wildlife. Designers and others can help show what this new city could be, why people might still want to call it home, and how government and other partners could support them.

Focusing on the Lower Ninth Ward, Team PaD developed a long-range vision for a low-density neighborhood of homes settled in a network of farms, tree nurseries, unpaved trails, and other forms of urban nature. The team also proposed a series of small, incremental steps to get there, beginning with the street – that simple piece of infrastructure that ties people together to a common public space, and is a highly visible symbol of either municipal investment or neglect. Modest streetscape improvements such as new planting, paving, and lighting can be made while adjacent lots are used for farming, stormwater management, and open spaces.

Low-density visions for vacant land were also key to Team Stoss’ economic development strategy. In contexts where physically aggregating nearby parcels would be impossible, the team proposed linking scattered sites operationally. For example, lots used for farming or industrial activities could be managed collaboratively for greater productive impact.

TEAM NOLEX (NEW ORLEANS LAND EXCHANGE)

Led by Kristi Cheramie of Ohio State University, with Jacob Boswell, Mattijs van Maasakkers, and Jennie Miller, NOLEX created a collaborative site-planning framework designed to bring stakeholders together around land parcels and shared interests – a process that builds capacity, facilitates decision-making, and creates an opportunity for pooling resources. View the team’s full proposal.

TEAM PaD (Policy as Design)

Led by James Dart of the New Orleans-based design firm DARCH with Deborah Gans, LoriAnn Girvan, and Marc Norman, Team PaD’s proposal demonstrated how collaborations across agencies, organizations, and communities could accelerate the scalability of vacant lot reuse initiatives to achieve greater ecological, social, and economic impacts in the region. View the team’s full proposal.

TEAM STOSS

Led by Chris Reed and Amy Whitesides of the Boston-based design firm Stoss Landscape Urbanism, with Teresa Lynch of MassEconomics, Jonathan Tate of OJT, Liz Ogbu, Ann Yoachim, Jill Desimini, Mike Brady, Byron Stigge, and Kate Kennen. Team Stoss developed proposals for unlocking the economic value of vacant land through job-creating land use strategies on aggregated and assembled lots. View the team’s full proposal.

RFQ PHASE

August 6, 2014: RFQ released

September 12, 2014: Deadline for questions and optional preregistration

September 29, 2014: RFQ submission deadline

RESEARCH AND DESIGN PHASE

October 10: Winning teams selected

October 22: Kick-off meeting in New Orleans

December 2014: Interim presentation in New Orleans: Design research

February 2015: Interim presentation in New Orleans: Strategies and scenarios

May 2015: Final presentations in New Orleans

March 2016: Van Alen Institute and NORA release final report

Jury

NICOLE BARNES

Jericho Road Episcopal Housing Initiative, New Orleans

MAURICE COX

Tulane City Center, Tulane School of Architecture, New Orleans

RENIA EHRENFEUCHT

University of New Orleans, New Orleans

WILLIAM A. GILCHRIST

City of New Orleans, New Orleans

JEFF HEBERT

New Orleans Redevelopment Authority, New Orleans

ARTHUR JOHNSON

Lower Ninth Ward Center for Sustainable Engagement & Development, New Orleans

DAN KINKEAD

Detroit Future City, Detroit

DAVID VAN DER LEER

Van Alen Institute, New York

ELIZABETH MOSSOP

Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge

TERRY SCHWARZ

Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative, Cleveland

DAVID WAGGONNER

Waggonner & Ball Architects, New Orleans

Futures Team

RICHARD CAMPANELLA

Tulane University, New Orleans

RENIA EHRENFEUCHT & MARLA NELSON

University of New Orleans, New Orleans

ELIZABETH MOSSOP & WES MICHAELS

Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge

ALLISON PLYER

The Data Center, New Orleans