With debates about housing in the media emerging daily, the book Affordable Housing in New York: The People, Places, and Policies That Transformed a City, edited by Nicholas Dagen Bloom and Matthew Gordon Lasner, is particularly timely.

Accompanied by an exhibition at Hunter College’s East Harlem Gallery, the book chronicles the legacy and current realities of subsidized housing in New York City, from experiments to relieve crowded tenements, and the mid-century prevalence of towers-in-the-park typologies, to today’s models of low-scale design and private-public partnerships.

We spoke with Lasner to learn more about the book, which was funded in part by a New York State Council on the Arts Independent Project grant through Van Alen. Learn more about applying for a 2017 NYSCA grant.

What was the genesis of Affordable Housing in New York?

We thought about what kind of book would fill a gap in the literature, expanding on what people had considered before in terms of different modes of design and finance, to look at the long-term lived experience of affordable housing: the impact subsidies have on the life of the city, arguably to make a case for more housing. We also wanted to invite others to share their own research, so we organized 30 people to contribute short case studies.

How might the book alter perceptions of affordable housing?

The idea of subsidized housing is sort of anathema to Americans. We wanted to tell stories about how important this housing has been to New York City by revisiting these projects and looking at them as real, living human communities.

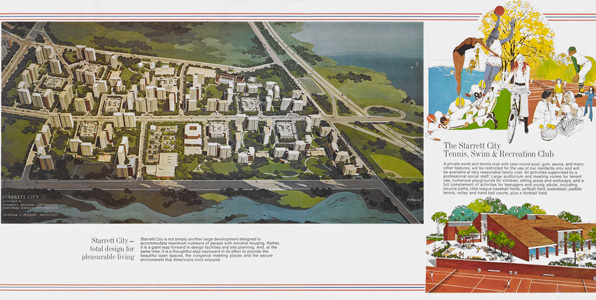

It was important to make a visual argument to complement the research and archival materials, so we invited photographer David Schalliol to look at the projects. He visited every complex we featured in the book, got into apartments and onto roofs, and shot some incredible images that have been really resonant. For all of the negative representations of affordable housing, there’s clearly a hunger for positive depictions. We also commissioned New York Institute of Technology students to create scale models of the developments. All of these materials focus on what it’s like to live in these places in a way that hasn’t been at the forefront of other conversations.

Why do you think that is?

I think there are a couple of reasons. First, it’s a very different kind of research—it’s a challenge to find the voices of ordinary people, especially working class and poor people in their homes.

Also, a lot of the conversation of housing has been dominated by architects and planners who are naturally going to think first about physical form. Part of the tension we wanted to explore is the perception that often housing developments’ architecture isn’t very good to begin with, or is out of favor, but it still provides people with rich home lives. People are extremely flexible and willing to adapt to many designs. For example, the tower-in-the-park has obviously been out of fashion for 60 years now, but the model was effective and satisfied the goals of their architects at the time.

When you begin to unpack the way tenants create lives out of subsidized housing, there are things equally important as the architecture and design. Without architecture, we wouldn’t have these complexes, but a lot of the conversations have focused on plans at the expense of how tenants feel about these places. It’s a different set of questions.

What lessons from your research may be applied today?

The overall lesson from the book is that we need subsidies. To build quality housing is very expensive in New York, and despite being a very rich city, it doesn’t have the resources or ability to levy the taxes for large-scale construction. Only the federal government has that ability. Even in the depths of the Depression, we got 40 years of federal support, and we produced a tremendous amount of housing—tens of thousands of low- and middle-income units. There are certainly benefits of the contemporary, more incremental projects in terms of the quality of the architecture, the fact that entire neighborhoods didn’t get leveled in the process, and there’s more community input. But we see that size matters too.

I think that another important lesson to think about is the question of for whom we build housing. Funding is so scarce, and it’s so contentious deciding between housing for middle-, low-, or very low-income, or supportive housing for formerly homeless people. One of the great lessons from before World War II was that communities were more mixed-income and had a variety of families living in them.

Another lesson from other periods is that perseverance and creativity matter. Today, people are so frustrated with rezoning and mandatory inclusionary zoning, the city is changing so rapidly, and gentrification is so inexorable—but after looking at many years of affordable housing, you realize that it was never easy. It was always contested. Every era thought it could solve affordable housing, and no era has. But it’s something we can always address, and take advantage of whatever resources we have at one time.

What advice do you have for people interested in launching their own independent projects?

Perseverance and creativity! It’s important to have a clear vision, have a clear argument, and to have an understanding of all of the complexities of putting together a project to garner support. People want to bet on a winning horse. Show that you’ve done your research and have a team that can execute what it’s putting forward.

Also, have committed producers, whether it’s a publisher, a gallery, or other collaborators. We were very lucky to work with an editor at Princeton Unviersity Press who understood the scale of our project, bringing together 30 contributors and a photo essay. And without support from NYSCA, we would have ended up with a very different book. A book with 60 black-and-white photographs would not have been nearly as powerful.

Applications for 2017 NYSCA grants available through Van Alen are open through midnight, March 14. Lasner will also be speaking with Bloom on March 16 at Cooper Union for the panel, The Next 100 Years of Affordable Housing.