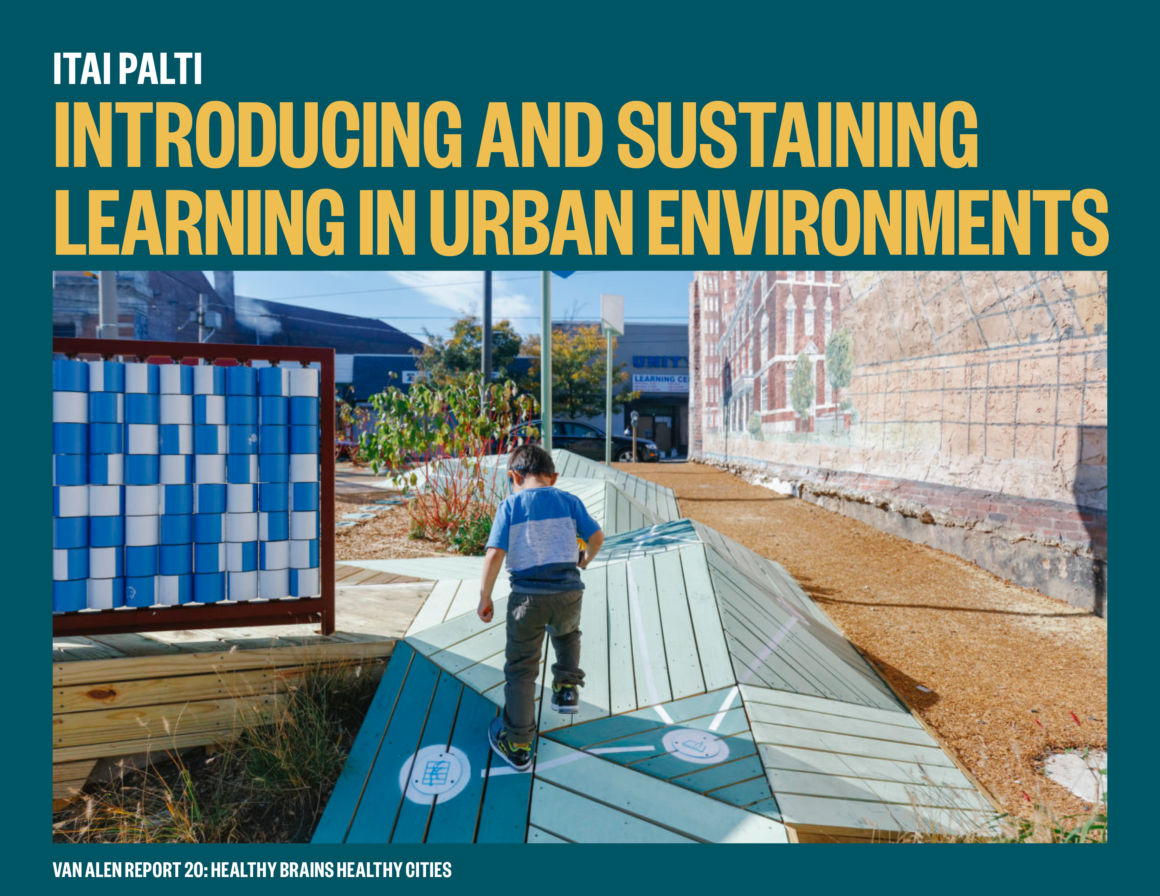

Early childhood is a critical stage for healthy brain development. While good public policy and public health have important roles to play in improving outcomes, architect Itai Palti, director of Studio Hume and designer of the Urban Thinkscape project in West Philadelphia, believes architects and planners can help as well. In this article from Van Alen Report 20, Itai spells out a recipe to build opportunities for learning and creativity on every sidewalk, bus stop, and corner of the city and offers advice for scaling up the impact of these learning-based interventions.

Intro

A day in the life of a city dweller is regularly characterized as a series of destinations: home, office, gym, restaurant, and so on. In our routine, the urban fabric is designated as a medium for getting from one place to the other for whichever activity is up next.

One of the biggest challenges we face in urban design is dismantling the long-standing premise that certain activities should be compartmentalized in parts of the city. For example, the notion of shuttling children to buildings where learning takes place is far from aligned with when and how children learn, and how they learn best. Only 20 percent of children’s waking hours are spent in schools, yet at that age the brain is most in need of opportunities to learn. Healthy brain development relies, among other factors, on regular positive interactions with caregivers and access to stimulating environments where children can learn in “active, meaningful, engaged, and socially interactive contexts.”

During the critical years of early childhood (under 5 years old), a child’s development is largely the responsibility of their caregiver and happens outside of nurseries and preschool. The city could offer far more to young families aside from pockets of safety in playgrounds and parks —refuges from the rest of the city designed with little consideration for their needs.

A city could be the ultimate environment for children to learn and explore. It is already filled with fascinating variations of spaces, textures, sounds, and people. Yet we design streets to prioritize movement above all, often at the cost of creating safe environments for families that encourage lingering and exploration.

Urban Thinkspace

The Urban Thinkscape project, conceived by pioneers of playful learning Kathy Hirsh-Pasek and Roberta Golinkoff, is based on addressing these challenges by enriching our streetscape with opportunities for children and caregivers to play and learn. Importantly, the project is outcome-driven, with datasets gathered pre and post-installation to measure the impact that the project was designed to achieve: increasing the quantity and quality of interactions between caregiver and children, using specific metrics indicative of healthy child development. The project’s pilot phase was launched in the Belmont neighborhood of West Philadelphia during the fall of 2017. I served as the project’s architectural consultant and helped develop the following design principles to guide these outcome-driven urban interventions. They are rooted in the rich literature available on child development, specifically in how playful learning can boost socio-emotional skills, executive functions, language, mathematics, and scientific thinking.

Integrated

Designs are part of the urban landscape used day-to-day.

The effectiveness of any infrastructure relies on correct dosage and distribution. A playground or park that is out of the way requires investment of time and effort by families to reap its benefits. Areas that are child-friendly shouldn’t be a destination but rather integrated into a family’s daily routine. In the case of Urban Thinkscape, a bus stop was used to make use of the time spent waiting. There have also been initiatives to integrate play and learning in supermarkets and libraries. This should encourage us to harness the potential of conditions wherever they can be improved to benefit both caregiver and child.

Intriguing

Designs must provoke curiosity of passersby and encourage further exploration.

Research on curiosity has given us some insights into how we can harness this very powerful drive to our benefit. Arousing curiosity opens a cognitive window for learning; experience is better encoded not just in relation to the source of arousal but to other events or stimuli that occur at the time. The science of arousing curiosity is largely based on the concept of the information gap, which refers to a balance of the familiar or easily attainable knowledge in contrast to what is unfamiliar or missing. Understanding the capacity of design to arouse curiosity is key to encouraging enjoyable exploration and interaction with an environment and among its users.

Intuitive

Good designs come with minimal instructions, if any.

Playful learning, also known as guided play, combines the enjoyable nature of free play with a scaffolding that supports learning goals. Not unrelated to the science of curiosity, guided play strikes a balance, giving agency to children to guide an experience with the help of nudges that might initiate certain exploratory behavior. Designs that are too prescriptive limit our capacity to be inventive, sometimes even in ways unintended by the designer. However, adding specific cues for the use of an installation can at times be helpful in encouraging engagement with it.

Interactive

A learning landscape is both interactive and fosters interactions.

Environments that allow users to make a mark can give children a sense of agency, linked to feelings of belonging and developing a sense of identity. Designing for interaction means adding cues for behavior that at times children might be reluctant to carry out. These cues can also prompt behavior that fosters inter-user interactions such as cooperation or guidance from caregivers. At times it is the caregiver that should be supported in their role, especially in a new environment or in interactions with a new game or playful installation.

SUSTAINING INVESTMENT IN LEARNING LANDSCAPES

Efforts to create learning landscapes are a form of placemaking. However, a lesson should be learned from what the majority of placemaking projects haven’t included: Measuring impact is crucial. The benefits of investing in enriching our urban environments must be backed up with evidence. A clear economic argument should be made so that efforts can be sustained by decision-makers in both the public and private realm by offering them the means to understand a return on investment.

In the case of learning landscapes, the economic argument is tied to framing children’s learning as a public health issue. Neuroscience is shedding light on the impact of poverty on brain development, for example, showing structural differences and reduced grey matter related to impaired academic functioning. The importance of early bonding between caregiver and child—another output of effective learning landscapes—is also linked to the long-term mental health of children. Both of these examples have a knock-on effect for quality-of-life indicators and future needs, including employment prospects and healthcare costs.

Projects like Urban Thinkscape measure human metrics that record the effectiveness of an environment in relation to the health issues being targeted. Only through this approach can learning landscapes take a place next to other forms of infrastructure that are essential for a healthy urban population.

References

1. Brenna Hassinger-Das, et al., “Learning Landscapes: Can Urban Planning and the Learning Sciences Work Together to Help Children?” Global Economy & Development at Brookings (Sep. 4, 2018).

2. Robert Winston and Rebecca Chicot, “The Importance of Early Bonding on the Long-Term Mental Health and Resilience of Children.” London Journal of Primary Care (Feb. 24, 2016), 12-14.

3. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Jennifer M. Zosh, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, James H. Gray, Michael B. Robb, Jordy Kaufman, “Putting education in ‘educational’ apps: Lessons from the science of learning,”

Psychological Science in the Public Interest (Apr. 13, 2015), 16, 3-34.

4. Brenna Hassinger-Das, Andres S. Bustamante, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, and Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, “Learning Landscapes: Playing the Way to Learning and Engagement in Public Spaces,” Journal of Research in Education Sciences (Jun. 30, 2018), 8, 72.

5. Matthias J. Gruber, Bernard D. Gelman, and Charan Ranganath, “States of Curiosity Modulate Hippocampus Dependent Learning via the Dopaminergic Circuit.” Neuron, (Oct. 22, 2014). 84 (2), 486-496.

6. Celeste Kidd and Benjamin Y. Hayden, “The Psychology and Neuroscience of Curiosity,” Neuron (Nov. 4, 2015), 449-460.

7. Deena Skolnick Weisberg, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, and Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, “Guided Play: Where Curricular Goals Meet a Playful Pedagogy,” Mind, Brain, and Education (May 17, 2013), 104-112.

8. Karen Guo and Carmen Dalli, “Belonging as a Force of Agency: An Exploration of Immigrant Children’s Everyday Life in Early Childhood Settings,” Global Studies of Childhood (Aug. 22, 2016), 254-267.

9. Nicole L. Hair, Jamie L. Hanson, Barbara L. Wolfe, et al., “Association of Child Poverty, Brain Development, and Academic Achievement,” JAMA Pediatrics (Sep. 2015), 169, 822–829.

With VAR 20, we explore the often hidden connection between mental health and urban environments. We hope this issue makes people more aware of the many ways our cities impact our health, our brains, and our lives. This article is the second piece featured in VAR 20. To receive future articles and interviews from Van Alen Report, please subscribe below.

SUBSCRIBE