We invited four leading researchers to share insights from their time exploring the intersection of science, the brain, and the built environment. In the interviews excerpted below, we asked about indicators of good brain health from cognitive performance to emotional well-being and the methods and technologies used to assess how different environments influence the brain to those ends. We also asked how city dwellers can rethink their relationship to the places they live, work, and play in order to improve their brain health and quality of life.

Sandra Chapman

Founder and Chief Director, Center for Brain Health, University of Texas at Dallas

Richard Davidson

Founder and Director, Center for Healthy Minds, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Frederick Marks, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, Six Sigma Green Belt

President, Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture, and Visiting Scholar, Salk Institute

John Medina

Professor of Bioengineering, University of Washington School of Medicine

Sandra Chapman

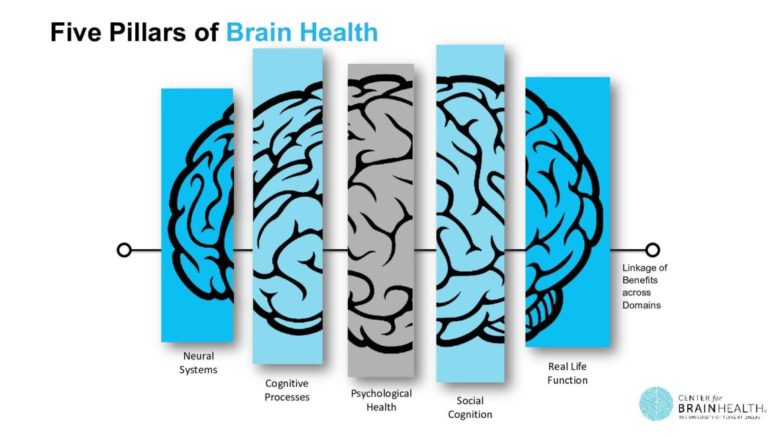

A healthy brain is one that allows us to thrive, not just to survive in our daily lives. It’s what allows us to make life decisions, solve problems, interact adeptly with others and really enjoy emotional balance. At the Center for Brain Health, we developed “pillars” of brain health that we measure. One is cognition, and when I say cognition, that’s not simply IQ: It’s really the ability to innovate, to synthesize. It’s what you’re trying to do right now [in this interview]: very quickly taking divergent ideas and boiling them down to the essence, looking for a takeaway point by strategically focusing on the most relevant information. It’s more than memory, more than speed of processing. It really is the ability to think and solve the problems that we’re faced with every day.

Courtesy Center for Brain Health – The University of Texas at Dallas

Another pillar is psychological well-being. If you’ve got some type of mental health disorder or you’re severely depressed, say frozen in bed, you have diminished brain health. Another area is the complexity of what you do—in other words, what is the level of productivity of what you’re doing. And another key area is socially adeptness. Being socially adept is probably one of the most important things to our cognition. It’s the most complex and most important.

Richard Davidson

From my perspective, the scientific evidence clearly shows that brain health is promoted when one’s emotional well-being is enhanced or is vibrant. Emotional well-being and brain health go together. For the brain to be in a kind of harmonious balance seems to require the mind to also be in a harmonious balance. I would say that the first and most important ingredient for brain health is really having a calm and clear mind.

Frederick Marks

I look to the National Institutes of Health’s definition of brain health, which centers on the brain’s ability to remember, learn, play, concentrate, and maintain a clear, active mind.

John Medina

I don’t like the term “brain health.” What I use is “typical functional” or sometimes “satisfactory functioning.” Because what is a healthy brain? Everybody has a psychiatric disorder—everybody! In general, though, you can say it’s usually an evaluation of two things. One is just straight-up cognitive ability, which is the ability to mobilize your IQ without external interference. The second is emotional regulation or affective stability. So when you’re looking to define what “brain health” is, the two piers are cognition and emotion.

Frederick Marks

What’s key is that we’re learning more. The more sophisticated these tools become, the better the reports. In the case of an electroencephalogram (EEG), you’re recording the process by which you have visual order or auditory stimuli. The EEG can be mobile, depending upon the size of it. Just in the last couple of years, one has been able to use that without the confinement of a long string of electrode wires. You can have remote devices and pick up activity on a computer. In the case of the non-mobile tools, you get an excellent resolution. That’s the benefit of something being stationary. In the case of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), you are detecting changes in blood flow. The MRI and functional MRI (fMRI) are much more stationary, and that’s true of the electromyogram (EMG) as well.

We can actually use these instruments both within a controlled room area as well as on the street. We can also use it with virtual reality (VR), which expands what you can test in real time. The combination of EEG and VR can take the form of being in a Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE). Even though you may consider that a static, stationary condition, [researchers] have so many opportunities within the CAVE to design the environment that subjects will experience. That is far more valuable data than you might be able to get conducting an experiment in real time on the street. And the feedback researchers get back allows them to keep making environmental changes. They can introduce many different environmental variables within a short period of time.

A Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE) can allow designers to introduce many environmental variables within a short period of time, while receiving immediate response feedback

Photo by Dave Pape

Eye tracking is becoming more and more mobile, so I do see that helping in many different instances in the future. It’s not just where one is looking, but it’s what then might be happening in terms of brain function as one is looking at it. Are we detecting within certain parts of the brain an activation that applies to a reduction in stress, or just the opposite?

We should not neglect building sensors, wearables and the development of algorithms for measurement. Each will be extremely important components of where the whole building industry goes in the future.

Richard Davidson

If we were doing experimental research, we would use modern tools with brain imaging to directly evaluate brain health. But in the absence of that kind of expensive assessment procedure, we can use certain proxies. We can look at behavioral measures of important constituents of well-being as a proxy for more direct measures of brain health. Those behavioral measures of well-being have been found in many laboratory studies to be associated with specific signatures, if you will, of direct measures of brain activity that would reflect brain health.

At the Center for Healthy Minds, we are actually creating a toolbox of measures that will be available on a smartphone, which measure the core constituents of well-being using objective measures, including neuroscientifically grounded behavioral tasks that could be administered on the smartphone. That suite of measures is not yet available, but it will be in the next couple of years. Something like that, I think, is potentially very valuable in this domain because it can easily be scaled; it simply requires a person to have a smartphone, which everyone has these days, and it could be easily deployed at scale. I think that can be done and will be available in the near future. We’re going to be geo-tracking as well, and using a variety of different classes of measure to provide as rigorous and as valid a measure as possible for each of the core empirically investigated constituents of well-being.

John Medina

If you’re interested in neurological responses, you can use behavioral, cellular, or molecular instruments. The behavioral instruments would be things like psychometric tests, processing speed, mean reaction times. If you wanted to go a little deeper you would go to cellular instruments like non-invasive deep imaging—fMRI, positron emission tomography scans (PET scans)—or we could stay on the surface and look at surface electricity. This would be instruments like event-related potential (ERP) and EEG.

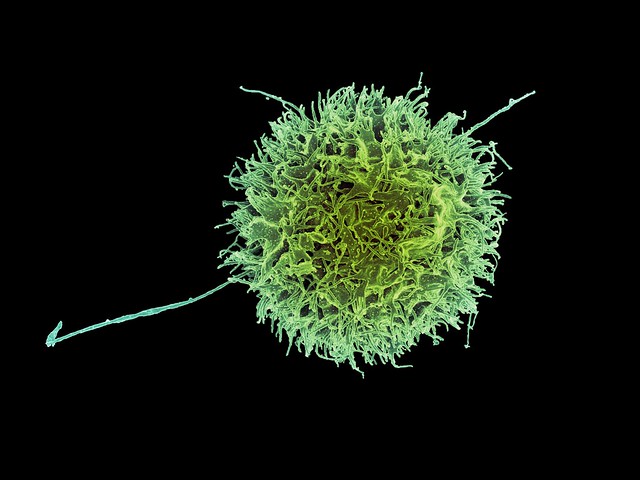

And then there are the molecular instruments. That’s measuring cortisol levels—if you want to observe someone’s stress hormones. And there are a number of other things you can get at. It isn’t just stress hormone levels. We know that green plants, for example, secrete phytoncides. And that actually has a strong impact on one part of the human immune response, “natural killer cells.” [see image/caption for definition] Phytoncides can increase the population of natural killer cells by 40 percent.

“Natural killer cells” destroy tumor cells and virus-infected cells without the stimulation of antigens. Image credit: NIAID

Richard Davidson

I think city dwellers, who may have a little less access to nature, can take advantage of what we do know about brain health and well-being. One of the most effective ways of promoting well-being is through social connection and the emotions that facilitate social connection, like appreciation and gratitude, and actions which help to also facilitate social connection, actions like acts of generosity. Those are all strategies that change the brain: we know that from hard-nosed scientific research and move the brain in the direction of a healthier baseline.

Social connection is anti-inflammatory. There’s good evidence to suggest that one of the most powerful strategies in reducing the molecular signals that are responsible for inflammation is social connection. Practices which can facilitate social connection are ones that we know reduce proinflammatory cytokines and actually have been found to alter gene expression for genes involved in the inflammatory cascade.

Frederick Marks

Now, certainly New York City is doing some very positive things with its active design guidelines. But I think we’re going well beyond that, particularly when we talk about brain health. Health has many more dimensions than what we’ve said it is in the past, and the impact of poor health on society has become far too expensive to ignore it. We also appreciate that people are living longer, so they’re vulnerable to things in health that we never had to think about in the past.

John Medina

We know that the color green focuses people. You put kids with ADHD in a room of 523 nanometers of wavelength: plant green, chlorophyll-like green. You know what it does? It focuses them. If you do a pre and post, they show focusing behavior. You need to give doctors in an emergency room a break every 100 minutes because if you don’t, the error rate climbs. It actually goes up two times. But if you give them a break every 100 minutes and they go into a room that’s green with 523 nanometers of wavelength, and there’s a plant there so they can sniff up the volatile biochemicals and change the parasympathetic system, their error rate goes back down to baseline.

Sandra Chapman

In cities, what I would look for are spaces that are interactional. Social cognition is important, and people love vibrant, multi-generational spaces where you see older people coming out, not just teenagers. We’re also trying to help empower people to think about what they’re doing in a given moment and which environment they should do that in to maximize performance. Rather than think, “I need this space to do more work in,” maybe be more nimble and think, where is the best place given what you’re trying to tackle.

One barrier to better brain health is people not realizing how much agency they have to influence their brain health. Our heart, we know that it’s under our influence. We know it’s our fault if we’re not eating properly and our cholesterol is not good. But our brain, we just think it’s a black box, even though cognitive neuroscience has shown that it changes from moment to moment. But that potential for improvement hasn’t been translated for people. Habits such as physical exercise, nutrition, sleep, and stress management contribute to the brain’s performance: the brain is not static.

With VAR 20, we explore the often hidden connection between mental health and urban environments. We hope this issue makes people more aware of the many ways our cities impact our health, our brains, and our lives. This article is the fourth piece featured in VAR 20. To receive future articles and interviews from Van Alen Report, please subscribe below.

SUBSCRIBE