How can a city respond to the crisis and opportunities of vacancy?

Competition Launch: January 2006

In the mid-2000s, many cities across the U.S. recognized the urgency of addressing vacant land, and began embracing new approaches to landscapes of abandonment and reuse. Philadelphia, with over 40,000 vacant properties representing nearly 1,000 acres, had become one of the nation’s foremost examples of urban abandonment and extensive sprawl. In January 2006, Van Alen Institute and the City Parks Association of Philadelphia invited participants from around the world to suggest compelling ideas for Philadelphia’s vacant land and to imagine long-term solutions that inspire change and reshape urban and natural forms throughout the city.

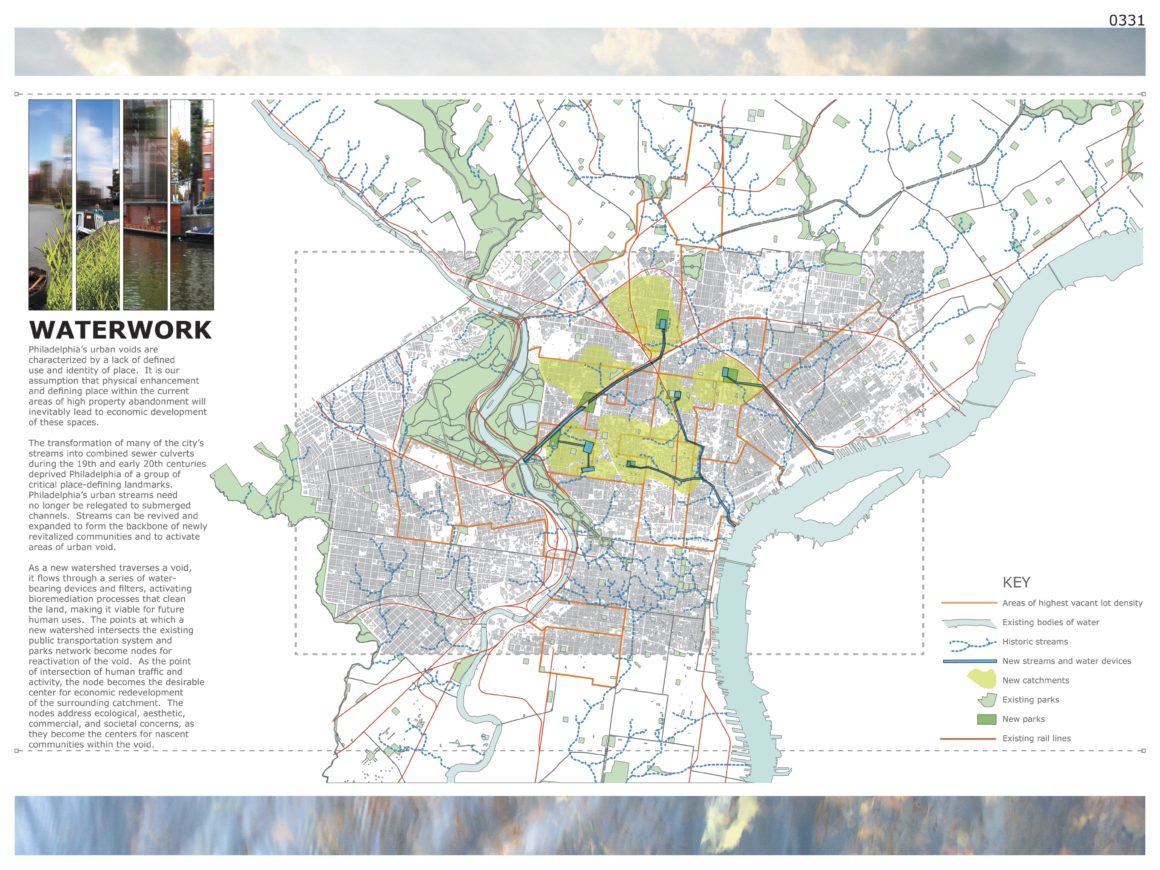

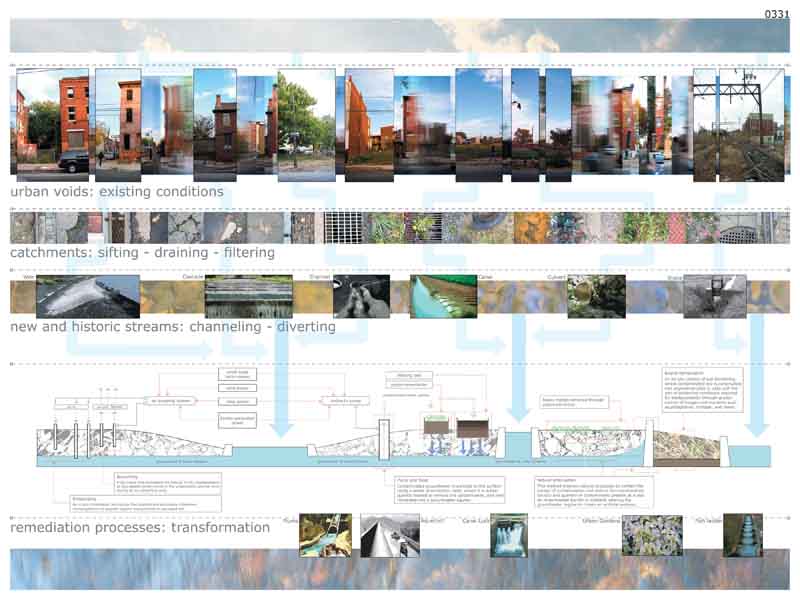

Rooted in a series of public forums that brought over 400 people to Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station, the three-phased project sought proposals that had potential for further development and realization, and ideas that were specific enough to take advantage of Philadelphia’s unique attributes yet broad enough to be applied to neighborhoods in other cities facing similar challenges. Of the 219 submissions in Phase One, five finalists were awarded funding to further develop their proposals in a second phase of the competition. In June 2006 a grand winner, Waterwork, by North Street Design, was selected for implementation. It was a design strategy that converted vacant sites throughout Philadelphia into “public green filters” by capturing and redirecting water flow. The winning proposal developed both recreational and filtration solutions for the use of naturally cleaned storm-water run-off, and illustrated groundbreaking and poetic ideas that add social and economic value to urban watersheds.

Summary & Schedule

Design Competition Objective

How can a city respond to the crisis of vacancy Philadelphia, with over 40,000 vacant properties representing nearly 1,000 acres, has become one of the nation’s foremost examples of urban abandonment and extensive sprawl.

The competition sponsors invited participants to suggest compelling ideas for Philadelphia’s vacant land and imagine fantastic long-term solutions that inspire change and reshape urban and natural forms throughout the city.

Schedule

The competition schedule is subject to change. Please check back to confirm all dates.

- Wednesday September 7, 2005 Registration begins

- Friday October 7, 2005 Late registration begins (5:00 pm)

- Monday November 14, 2005 Registration ends; deadline for questions (5:00 pm)

- Monday November 21, 2005 Answers posted online

- Friday January 6 2006 Entries due online (5:00 pm)

- February 2006 Results announced; entries exhibited to the public

Competition Awards

In the first phase of the competition, up to five finalist teams will receive $5,000 each to continue on to the next phase of the competition, Reconnecting the Lots.

Registration

Registration is now closed. The registration fee is $150 USD (late registration, after 5:00 pm Friday October 7, 2005, is $180 USD). Please note that this fee includes high-quality printing, mounting, and lamination of digitally submitted boards. This process will eliminate all printing and shipping costs for entrants.

LANDvisions

Phase I: Our Voices, Our Future

Town Meeting

May 5, 4-8 pm

Amtrak 30th Street Station

The first gathering brought over 400 people to 30th Street Station to imagine possibilities for vacant land in the city. Participants were asked to identify what they love about the city: all ideas were collected and then voted upon using keypad polling, the results of which appear on thePhiladelphia LANDvisions website. The program continued with a series of short presentations providing background on the current state of vacancy in the city as well as an overview of the ecology of the region. The session continued in smaller groups of ten. Participants both clarified their ideas and expressed their hopes and aspirations for the future of the city. Using innovative technology techniques, these ideas were captured and made immediately available on the website for public appreciation and ongoing involvement.

The River Corridors

May 18, 4-8pm

The Hyatt Regency Philadelphia at Penn’s Landing

This session applied the ideas from the Public Community Forum to our river corridors. The meeting began with a series of presentations on existing or planned projects that integrate our rivers with recreational, residential, and commercial uses. The session continued with a keypad vote on the ten most critical themes, including “Living with Water,” “Creating New Communities,” and “Economy and Jobs” that emerged from the May 5th session. Participants then broke into small groups to discuss the inherent values, guiding principles, and strategies that follow from a particular theme. Groups then shared their ideas with the larger forum; you can view them on the Philadelphia LANDvisions website. The meeting concluded with a vote ranking the importance of each theme.

The Neighborhoods Session

May 25, 4-8pm

City Hall

The final session focused on how vacant lands can be used to transform Philadelphia’s neighborhoods. After an initial keypad polling exercise to determine the characteristics of those present, participants began by discussing the assets and liabilities of different types of vacancies within the city. Then a mapping exercise challenged participants to brainstorm uses for vacant lands in an unidentified Philadelphia neighborhood. While some groups concentrated on the environmental possibilities of vacant sites, others directed their attention to social or economic options. Finally, participants engaged in a storytelling exercise in which they shared memories of their neighborhood’s past and their hopes and wishes for its future.?The keypad polling results, lists of assets and liabilities, maps, and hopes and wishes can be viewed on thePhiladelphia LANDvisions website. Additionally, audio recordings of the storytelling exercise are also available online.

September 2005 -February 2006

Entrants from around the world are now asked to imagine new possibilities for designing a comprehensive view of Philadelphia’s urban fabric that creates a new relationship between ecology and the built environment. Submission of ideas will make visible concepts that reconnect vacant land to the city’s existing green infrastructure. A prestigious multidisciplinary jury will review and evaluate all submissions, making awards on criteria that acknowledge a range of design ideas. The jury will select up to five finalists who will receive monetary prizes and proceed into the third phase of the competition process.

Phase III: Reconnecting the Lots

February 2006-May 2006

During the third phase, Phase II finalists will further develop strategies for implementing their ideas. Teams will prepare a site-specific design proposal, focusing on a designated area in Philadelphia. An advisory committee and project partners will provide technical support as needed, matching professional partners with the semi-finalist teams. Team members will be encouraged to interact with neighborhood groups, experts in the field, members of the business community, and elected officials while developing their final submissions. A prestigious multidisciplinary jury will review the final submissions. The winning submission will receive recognition as well as a monetary award. A key outcome from this competition will be the development of innovative designs that will directly influence the plans of the decision makers and implementers in Philadelphia. In addition, the process will help formulate principles and emerging best practices for issues of vacancy throughout the country.

Program & Criteria

Program Description

Philadelphia needs a compelling long-term vision for developing its vacant lots, a strategy that envisions how vacancy in Philadelphia can be changed from an obstacle (vacancy as absence) to an asset (vacancy as possibility).

The jury will seek out powerful, transforming ideas with the potential for further development and realization, ideas that are specific enough to take advantage of Philadelphia’s unique attributes yet broad enough to be applied to neighborhoods throughout the city.

The Urban Voids competition, an idea generating process,?is the second phase of Philadelphia LANDvisions. For this phase of the competition, entrants are free to?suggest program elements that best express their idea and are in keeping with the competition aim (specific program elements will be developed in the next phase). Community-generated ideas can be found in the results of Phase I: Our Voices, Our Future: A Community Visioning Process.

Rules and Eligibility

Eligibility

The competition sponsors encourage entrants to work in teams, although individuals may also enter. At least one primary registrant must be a graduate of one of the following degree programs:

Accredited professional architecture program

Accredited professional landscape architecture program

Accredited professional urban planning or urban design programOR

If no primary registrant is a graduate of one of the above programs, the team must include an advisor (faculty member or practicing professional) who is a graduate of one of the above degree programs.

The competition organizers encourage students, members of community groups, and others interested in these issues to enter the competition. Connections to potential professional advisors can be found through organizations such as the Community Design Collaborative in Philadelphia, your local AIA chapter, your local ASLA chapter, or your local APA/AICP chapter.

Team members fall into three possible categories: primary registrants (one of whom will be the contact), advisors, and consultants. Awards will be given to primary registrants, but all team members will be acknowledged in publications and exhibitions.

Primary Registrants: The main team members, responsible for the design. One of the primary registrants is the contact.

Advisors: Advisors may be faculty and/or practicing professionals who are graduates of one of the accredited programs listed above. Advisors provide technical, design, and presentation advice to their team.

Consultants: Consultants are optional team members who provide consultation or assistance to the primary registrants (for example rendering assistance or engineering advice), but are not responsible for the design.

To better formulate creative solutions to the multi-faceted issue of vacancy in Philadelphia, the competition sponsors encourage multidisciplinary teams. Members could include geographers, botanists, sculptors, sociologists, engineers, ecologists, zoologists, geologists, historians, agronomists, photographers, horticulturists, folklorists, gardeners, hydrologists, historians, artists, etc.

The competition is open to all individuals, teams, and firms from around the world with the following exceptions and qualifications:

- The trustees and employees (and immediate family members of the trustees and employees) of Van Alen Institute, the City Parks Association, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, the Pennsylvania Environmental Council, and The Reinvestment Fund are not eligible to enter as primary registrants, advisors, or consultants.

- Only one entry per registration will be accepted. Entrants who wish to submit more than one project must register for each scheme they intend to enter by the registration deadline.

The competition is anonymous and the jury will not be informed of any aspect of the authorship of any submission.

Entries which do not meet the following criteria will be disqualified and will not be viewed by the jury.

Entrants are required to register for the competition prior to submitting their entry. Registration is $150 USD until 5:00 pm October 7 (late registration, until 5:00 pm November 14, is $180). Registered entrants will receive access to the password-protected Download Images page.

This fee includes registration fee in addition to high-quality printing, mounting, and lamination of submitted digital boards. To ensure fair evaluation of all boards, to eliminate shipping damage, and to eliminate printing and postage fees for entrants, all entrants must submit digital files. Van Alen Institute will be responsible for printing, mounting, and laminating all submitted boards. All files will be professionally printed as high-quality (200 dpi) prints, laminated, and mounted on 1/4″ Gator board.

Also note that there is no additional print information?all information is available online.

Entrants can only register online and can pay by credit or debit card via a secure system. Upon completion of online registration and payment, entrants will receive their registration confirmation and registration ID number, as well as access to additional downloadable images.

All payments are final. The competition will not be able to offer refunds for registrants who do not submit an entry.

After 5:00 pm Friday October 7, 2005 the registration fee will be increased to $180 USD.

Deadline: All submissions must be received online no later than 5:00 pm Friday January 6, 2006. Submissions may NOT be delivered in person or by mail. See below for format requirements.

Anonymity: The submission shall have no name or mark that could serve as a means of identifying the project, other than the registration number, which entrants will receive by email after completing the registration process (including payment). Both PDF files must include the entrant’s registration number in the upper right hand corner in either 36 point plain black text on a white background or 36 point plain white text on a black background.

Late Submissions: Submissions received after 5:00 pm on Friday January 6, 2006 will be considered late entries and will be deleted without being viewed.

Drawings: Plans, sections, and perspective views are suggested, but the scale of each is left up to the entrants. Additional drawings may be included if they will further explain your project.

Text: A text statement of no more than 250 words explaining the project’s concept, design intent, and phasing should be included on one of the two boards submitted, as well as in a separate Microsoft Word compatible (.doc) file.

Confirmation: Entrants will receive an automatic email confirmation upon receipt of both registration and payment, and again on receipt of a complete submission.

Submission Format Requirements

Please read all submission requirements carefully. Files that do not meet the requirements will be rejected. No resubmissions will be allowed after the deadline has passed. If you have any questions, you may submit them online until 5pm November 14, 2005. Answers will be posted on this website.

Each team shall submit two boards explaining their project. One of the boards must include a text statement of no more than 250 words on the board itself (the same text should be saved as a Microsoft Word compatible file). The boards must be uploaded to the competition website in both of the following formats:

Two 30″ x 40″ PDF files, 200 dpi, 8MB maximum size for each file

(primary files for printing boards)Two 600 x 800 pixel JPEG files, 72 dpi, 150K maximum size for each file

(web-ready files for online exhibition)

In addition, the following two files are also required:

One 100 x 100 pixel JPEG file, 72 dpi, 20K maximum size

(image detail of your choice from either board for online thumbnail)One Microsoft Word compatible (.doc) file containing the same project description text (250 words or less) as the first board

All files must be in LANDSCAPE format (long side horizontal, short side vertical). All files must be named with the registration number you received when you submitted your registration, followed by an underscore and A, B, etc. For example, the files for registrant 0000 would be called:

Board A: 0000_A.pdf (large file), 0000_A.jpg (small file for web)

Board B: 0000_B.pdf (large file), 0000_B.jpg (small file for web)

Other: 0000_thumb.jpg, 0000.doc

Each PDF file must include the entrant?s registration number in the upper right hand corner in either 36 point plain black text on a white background or 36 point plain white text on a black background.

For PDF files, graphics should be set to 200 dpi/ppi. If printing to PDF from Illustrator, for example, choose Effect -> Document Raster Effects Settings -> Resolution -> Other: 200 ppi.

Layout: Two 30″ x 40″ landscape boards are required. Each board must include the entrant’s registration number in the upper right hand corner in either 36 point plain black text on a white background or 36 point plain white text on a black background.

The first board must include the project description text (the same text will also be submitted separately as a Microsoft Word compatible .doc file), a small diagram, plan, or sketch to place the project in context, and a single large image that conveys the intent of the project. The suggested layout for this board is: large image on the right, text at the bottom of an 8″ column on the left, and an overview, sketch, or diagram in the top of the 8″ column on the left (above the text).

The second board should contain whatever additional drawings, diagrams, or sketches are necessary to further explain the project.

Finalists: in the first phase of the competition, up to five finalist teams will receive $5,000 each to continue on to the next phase of the competition, Reconnecting the Lots.

Public Exhibition and Copyright: Van Alen Institute and the CPA shall retain ownership of all prize-winning design submissions. Van Alen Institute plans to hold both an online and a gallery exhibition of work submitted in the competition following the jury. In entering the design competition, entrants grant Van Alen Institute and the City Parks Association unrestricted license to exercise the entrants’ rights regarding their design submissions, including, but not limited to, reproduction, preparation of derivative works, distribution of copies of the design submission, and the right to authorize such use by others.

Announcement, Displays, and Publication of Results: When entering the competition, the registrant and all team members recognize the competition’s program as the intellectual property of Van Alen Institute and City Parks Association and agree to credit the two organizations by name in any subsequent exhibition or publication of the project. Entrants will be credited on all online and print material published by the organizers of the competition.

Philadelphia Orientation

Philadelphia sits at the confluence of the Delaware River and its smaller tributary, the Schuylkill, in southeastern Pennsylvania, about 150 miles northeast of Washington DC and about 100 miles southwest of New York City. Most of the city lies between the two rivers in a riparian buffer zone where hundreds of underground streams flow, although several Philadelphia neighborhoods collectively known as West Philadelphia (including Eastwick, Powelton, Mantua, and University City) are located across the Schuylkill River to the west, and ferries and bridges connect Philadelphia with Camden, New Jersey across the Delaware River to the east.

The center of Philadelphia is located at 39’59’53” north, 75’8’41” west. The current population of Philadelphia is about 1.5 million, down from a peak of about 2 million in 1950.

Philadelphia’s Natural Resources

Philadelphia has an extensive parks system anchored by Fairmount Park and including urban squares, natural areas (including stream corridors, woodlands, meadows and wetlands), street trees throughout the city, and many neighborhood parks. The Philadelphia parks system comprises about 8,900 acres in all.

The city of Philadelphia spans two physiographic regions, the Piedmont and the Inner Coastal Plain, with the dividing line occurring at the fall line of the Fairmount Water Works, where the first falls on the Schuylkill River are located.

Philadelphia generally receives from 30 in to 50 in of precipitation most years (including about 20 in of snowfall). Average high temperatures vary from around 30ºF in winter to around 87ºF in July and August, although high temperatures above 90ºF are not uncommon in during summer.

Local wildlife includes various species of coyotes, foxes, beavers, peregrine falcons, red-tailed hawks, beavers, otters, raccoons, snakes, rabbits, owls, frogs, deer, turtles, fish, and butterflies. In addition, many migrating birds stop over in Philadelphia during the spring and fall migration seasons. Local flora includes purple coneflower, swamp milkweed, butterfly weed, swamp sunflower, swamp mallow, blue-flag iris, bee balm, cinnamon fern, flowering dogwood, quaking aspen, black cherry, willow oak, basswood, witch-hazel, and wild rose, among many others.

Philadelphia History

Early History

William Penn received a land grant from King Charles II of England for land west of the Delaware River, where he looked to found a colony based on the Quaker ideals of freedom and religious tolerance. He named and chose the site for Philadelphia, the location of an earlier Swedish settlement, and specified a grid with wide streets to avoid another disaster like London’s 1666 Great Fire, as well as to embody his vision of a “Greene Countrie Towne.” The original location of Philadelphia comprises present day Center City and the waterfront area around Penn’s Landing.

The original inhabitants of the Philadelphia area included the Lenape who, despite William Penn’s pacifist Quaker beliefs, were decimated by European diseases and eventually forced further west.

Philadelphia’s 1793 yellow-fever epidemic (the first in a series) killed nearly 5,000 people in less than five months, and drove many wealthy citizens to the suburbs. Philadelphia recovered, and remained the largest city in the North American colonies until overtaken by New York City in 1836.

Philadelphia continued to grow, becoming an early railroad hub, which (together with its location on the Delaware River), made it a major industrial center. In 1854 the city annexed surrounding suburbs to reach its current size of 159 square miles.

Post-Industrial/Vacancy

As in many eastern American cities, Philadelphia’s fortunes fell with the decline of industrial manufacturing after World War II. Exacerbated by Federal highway development and Federal housing policies that encouraged new development outside the city, as well as racial and political unrest inside the city, large areas of Philadelphia’s Center City and surrounding neighborhoods fell into disrepair. In addition, narrow lots crowded with small, aging townhouses (including Philadelphia’s distinctively tiny three-story “Trinity” townhouses with one room per floor) became less attractive to Philadelphians than larger houses in outlying suburbs. Philadelphia has consistently lost residents since 1950. Between 1950 and 1990 the city lost over 400,000 residents. In the 1990s alone another 4.3% of the population left, many headed for nearby areas, including Montgomery County.

The city has razed many of its unsafe abandoned buildings leaving vacant lots, while others remain standing. Today Philadelphia has the highest per capita vacancy rate in the country. As of the 2000 census, almost half (45%) of the residential street segments in Philadelphia contained some kind of abandoned property and more than one third (36%) contained at least one vacant residential structure, totaling approximately 26,000 vacant residential structures and nearly 3,000 vacant commercial and industrial structures?more than 40,000 vacant parcels to date.

Renaissance

Recently Philadelphia has experienced regeneration in and around Center City, as well as redevelopment in outlying areas of Philadelphia, including parts of Manayunk, Germantown, and East Falls. This renaissance, however, has not reached every neighborhood. Pockets of urban blight remain throughout the city, particularly in the ring of neighborhoods around the city center, including North Philadelphia, Kensington, Parkside, Grays Ferry, Point Breeze, and others.

Recent initiatives to revitalize Philadelphia include the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society’s Philadelphia Green project to “clean and green” vacant lots throughout the city, and the City of Philadelphia’s Neighborhood Transformation Initiative (NTI), an unprecedented effort by the City of Philadelphia to counter the history of decline in Philadelphia and revitalize Philadelphia’s neighborhoods.

You can view a map showing the locations of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society’s vacant land stabilization projects (2.6MB PDF file). For more information, visit the PHS website.

FAQ

REGISTRATION

Can I modify my registration information or add a team member later?

The Update Registration page is currently unavailable, but will be working very soon. As soon as that page becomes available you will be able to change any of your registration information (including the names of team members) except your registration number.

What additional information will I receive after I register?

After registering and paying the registration fee, you will receive online access to high resolution photos and maps, as well as Adobe Illustrator and PDF versions of the maps. Thumbnails of these maps and photographs are posted on the Images page.

Why is the registration fee higher than previous Van Alen Institute competitions?

In previous competitions entrants were required to print, mount, and ship their entries to our offices; for this competition entrants will submit all files digitally. The two boards per entrant will be printed, mounted, and laminated by the competition sponsors to be used for both the jury and a public exhibition of all entries. By printing the boards at the same time we will be guaranteeing uniform high quality and preventing shipping damage. This process will eliminate all printing and shipping time and expenses for the registrant. The registration fee was raised to help cover this cost.

May I submit more than one project and with different team members?

You may register and submit as many projects as you like. Each submission requires its own registration and payment. Each registration will have a different username and registration number. Different registrations may include either the same or different team members.

When I try to register, I receive an error message stating? This username/password is already in use. Please try another?. What should I do?

Most likely this happened because you started to register before, but did not complete the payment process. The registration, payment and activation processes must be completed together. Either contact Van Alen Institute to remove your incomplete registration, which will allow you to use your intended username and password, or you may choose to register with a different username.

I received my degree from a European school. Am I eligible?

Yes, as long as your degree is equivalent to one of the degrees in the registration form (MArch, BArch, BLA, MLA, MAUD, MUP) or you have an advisor with an equivalent degree, you are eligible.

I am not a current student, nor do I have a professional design degree. Do I need an advisor?

Yes, anyone who does not have a professional design degree (MArch, BArch, MLA, MAUD, MUP or equivalent) from an accredited school must have an advisor who does.

I have a degree in architecture history. Am I eligible?

You must have a professional design degree (MArch, BArch, MLA, MAUD, MUP or equivalent) from an accredited school to enter without an advisor. Anyone may enter with an advisor who has a professional design degree from an accredited school.

Are we allowed to register in the 2nd phase of the competition if we didnt participate in the first?

No. In the first phase of the competition, up to five finalist teams will receive $5,000 each to continue on to the next phase of the competition.

I will receive my professional design degree before the submissions are due but after the registration deadline. Do I still need to include an advisor on my team?

As long as you have your degree before the submission deadline, you do not need an additional advisor.

What will be the first place award for the second phase?

The winner of the second phase of the competition will receive a monetary award (TBD) and the opportunity to work with a team towards possible implementation.

What is the site for this competition? Will registered entrants receive maps for a specific site?

The site is the vacancy found throughout the entire city of Philadelphia; there is no specific site for this stage of the competition. The competition sponsors are seeking ideas that are specific enough to take advantage of Philadelphia?s resources, while still being flexible enough to be applied to any neighborhood in Philadelphia suffering from urban vacancy. In the next phase of the competition finalists will be given a specific site to work with.

What is the ownership status of the vacant lands?

The lots are in a variety of ownership states ranging from city to private ownership, depending upon the location and history of the specific area. For this first phase, ownership should not be a primary factor in preparing a design response.

In the 2nd phase, is there only 1 specific site or the 5 finalists can choose their own sites?

The sites for the second phase have not been determined. The organızers will work wıth the finalists to select the most suıtable site/s for their proposal.

What’s the typical size of a street block in Philadelphia? How tall are the typical row houses? How wide are they per house? What’s the size of the vacant lots on your photos?

Street blocks in Philadelphia are usually 400x400ft. This ?block? is the major block cell in Philly divided by main streets. This block cell is then composed of 3 smaller blocks of 400x115ft divided by alleyways. This pattern is clear throughout the city (check out an aerial of north Philly) Typically you find 2-story structures on alleyways and 3-story structures on main streets. This was designed according to the block cell described above. Width goes from 10-12ft wide on alleyways to 15-24ft on main streets. Lots are usually 10-12ft x 45-55ft (length) on alleyways and 15-24ft x 55-75ft (length) on main streets. Of course, you get all possible combinations of the above (especially in highly vacant areas). In addition you have other patterns in lower density areas such as the northeast and northwest sections of the city.

Could you, please give us the exact units your “Vacancy lot density” map is measured in? Is it the amount of vacant lots per mile, or per 10.000 sq meters, or any other?

The map is just the number of vacant lots by neighborhood. It is not a ratio of any kind.

Can I receive access to the high-resolution images before registering?

No, only registered entrants can access the high-resolution images.

Will additional maps or drawings (Sanborn, topography, CAD, etc.) be provided after registration?

We have provided general maps and aerial photographs, and encourage registrants to utilize any additional resources that they feel are necessary to communicate their idea. The competition partners anticipated a variety of map/information requests, and have provided an extensive bibliography which includes specific links to additional data sources.

Will I receive additional information in the mail?

No, all information is available on this website. There is no additional print information.

What scale should my submitted drawings be?

There is no required scale, although you should clearly mark scale and/or dimension on any scaled drawings. You should choose the drawings, scale and layout that best communicates your design idea. Board A must include a single large image (of your choice), the text of your project description (250 words or less), and your registration number. It may also include an additional small image. Board B must include your registration number, and may include whatever drawings, details, or images you decide are necessary to explain your concept. The important thing is that your idea is clearly communicated.

Where can I find a copy of the May 5 town meeting notes [hopes + aspirations] and the river corridors workshop and its resulting theme discussions, as well as the neighborhoods session with the list of assets, liabilities, maps, hopes and wishes?

This information is on the Philadelphia LANDvisions site (Link on top left corner of page).

Jurors

Phase One

Diana Balmori, Principal, Balmori Associates and Co-Vice Chair, Van Alen Institute Board of Trustees

Ramon Cruz, Policy Analyst, Living Cities Program, Environmental Defense

James Corner, Founder and Director, Field Operations and Chair, Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning, University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Design

Milton S. F. Curry, Principal, OrbitMCA Design Studio and Associate Professor of Architecture, Cornell University

Graham Finney, President, 21st Century League

Eva Gladstein, Director, Neighborhood Transformation Initiative, City of Philadelphia

Jerold Kayden, Co-Chair, Harvard Graduate School of Design, Department of Urban Planning and Design

Deenah Loeb, Executive Director, City Parks Association of Philadelphia

Jody Pinto, Environmental Artist

Shawn Rickenbacker, Founding Partner, Creative Front Architecture

Anne Spirn, Professor of Landscape Architecture, MIT Department of Urban Studies & Planning

Phillip Thompson, Associate Professor of Urban Politics, MIT Department of Urban Studies & Planning

Cathy Weiss, Executive Director, Claneil Foundation

Phase Two

Carl Anthony, Program Officer and Director, Sustainable Metropolitan Communities Initiative, Ford Foundation

Diana Balmori, Principal, Balmori Associates and Co-Vice Chair, Van Alen Institute Board of Trustees Julie Bargmann—Principal, D.I.R.T. Studio

Blaine Bonham, Jr., Executive Director, The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society

Eva Gladstein, Director, Neighborhood Transformation Initiative, City of Philadelphia

Deenah Loeb, Executive Director, City Parks Association of Philadelphia

Rick Lowe, Founding Director, Project Row Houses

Jeremy Nowak, President and Chief Executive Officer, The Reinvestment Fund

Christopher Sharples, Co-founder and Principal, SHoP Architects

Brigitte Shim, Principal, Shim-Sutcliffe Architects Inc.

Patrick Starr, Vice President, Pennsylvania Environmental Council

Project Team

Project Lead

City Parks Association of Philadelphia

City Parks Association stimulates visionary thinking about natural resources and open space in the urban community. From its founding in 1888, City Parks Association has encouraged the establishment and maintenance of public parks and open spaces in the city of Philadelphia. City Parks programs foster ongoing dialogue and collaborative action among people committed to the stewardship of our city?s natural resources. www.cityparksphila.org

Core Team: Organizational Partners

Pennsylvania Horticultural Society

The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society is a not-for-profit membership organization founded in 1827 to motivate people to improve the quality of life and create a sense of community through horticulture. Programs of the PHS include the annual Philadelphia Flower Show, the Philadelphia Green program, and the McLean Library. www.pennsylvaniahorticulturalsociety.org

Pennsylvania Environmental Council

The Pennsylvania Environmental Council improves quality of life for all Pennsylvanians by enhancing the Commonwealth’s natural and built environments by integrating advocacy, education and implementation of community and regional action projects. The Council values reasoned and long-term approaches that include the interests of all stakeholders to accomplish its goals. www.pecpa.org

The Reinvestment Fund

The Reinvestment Fund Inc. builds wealth and opportunity for low-wealth communities and low- and moderate-income individuals through the promotion of socially and environmentally responsible development. TRF makes loans, equity investments, and grants to affordable housing, small business, community services, commercial real estate, workforce development, and energy conservation projects; provides relevant and high quality research, information and policy ideas to government, nonprofit institutions, and private sector partners; and builds public and private partnerships and systems that connect low-wealth people and places with opportunity, information, and resources. www.trfund.com

Competition Advisor

(Development & Management)

Van Alen Institute: Projects in Public Architecture

Van Alen Institute is a non-profit organization dedicated to improving design in the public realm through a program of exhibitions, competitions, publications, workshops, and forums, and is an advocate for active and accessible waterfronts. Founded in 1894 as the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects, the Institute was renamed in 1996 after William Van Alen, the architect of the Chrysler Building and its largest benefactor, and reorganized to focus on the public realm. Based in New York, the Institute?s projects initiate interdisciplinary and international collaborations between practitioners, policymakers, students, educators, and community leaders. past.vanalen.org

Project Funding

The project team would like to thank the following organizations for supporting this project:

-

- The City of Philadelphia Office of Housing and Community Development

- The Claneil Foundation

- The Samuel S. Fels Fund

- The National Endowment for the Arts

Competition Credits

Competition Advisor

Susanna Sirefman, Van Alen Institute

Competition Manager, Phase I (2005)

Jonathan Cohen-Litant

Competition Administration

Marcus Woollen, Jonathan Cohen-Litant, Ori Topaz, Van Alen Institute

Website Design

Jonathan Cohen-Litant, Kirsten Hively, and Marcus Woollen, Van Alen Institute; Doug Meehan, CPA; Liron Topaz, Graphipus

Aerial Photography

Jonathan Cohen-Litant

Maps

Vicky Tam, Cartographic Modeling Laboratory, University of Pennsylvania

Additional Photography

Philadelphia Horticultural Society; Students from Gideon Elementary School and Vare Middle School in Philadelphia, under the direction of Tory Read

Bibliography

Books

- Anderson, Elijah. Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000.

- Nash, Gary B. Forging Freedom: The Formation of Philadelphia?s Black Community, 1720-1840. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991 (reprint).

- Stevick, Philip. Imagining Philadelphia: Travelers’ Views of the City from 1800 to the Present.Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996.

- Alotta, Roberta. Mermaids, Monasteries, Cherokees and Custer. Santa Monica: Bonus Books, 1990.

- Nese, Jon M. and G. Schwartz. Philadelphia Area Weather Book . Philadelphia : Temple University Press, 2005.

- Kavanagh, James. Philadelphia Birds. Phoenix, AZ: Waterford Press, 2001.

- Colimore, Edward. The Philadelphia Inquirer?s Guide to Historic Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Camino Books, 2003.

- Mauger, Ed. Philadelphia Then and Now. San Diego, CA: Thunder Bay Press, 2003.

- Weigley, Russell E. (Ed). Philadelphia: a 300 Year History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1982.

- Lapsansky, Emma Jones and Anne A. Verplanck (Eds). Quaker Aesthetics: Reflections On a Quaker Ethic in American Design. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

- Rockland, Michael Aaron. Snowshoeing Through Sewers: Adventures in New York City, New Jersey, and Philadelphia. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994.

Reports

- Reports on neighborhood blight and redevelopment by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission

- Vacant Land in Philadelphia, a 1995 report by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission

- The Revitalization of Vacant Properties, a report by the International City/County Management Association

- The National Resources Defense Council’s 2003 report on pollution in Philadelphia’s drinking water

- The Housing Alliance of Pennsylvania’s report and action guide for vacancy in Pennsylvania

Websites

The City of Philadelphia and Its Neighborhoods

- The official website of the City of Philadelphia includes links to agencies, officials, and policy documents

- Pennsylvania Spatial Data Access website with Pennsylvania GIS information, including online GIS tutorials

- The cartographic Modeling Lab at the University of Pennsylvania

- Maps and photographs from the city of Philadelphia, including aerial photos, zoning maps, and a searchable photo archive

- Historical background on Philadelphia from the Independence Hall Association in Philadelphia

- The website companion to the PBS film Philadelphia Diary based on interviews with Philadelphia residents

- The EPA website, with a searchable “EnviroMapper” and “Envirofacts,” as well as watershed information

Vacancy and Vacancy Initiatives in Philadelphia

- Philadelphia NIS NeighborhoodBase, with GIS maps and charts of Philadelphia neighborhoods

- Blight and redevelopment plan information from the Philadelphia City Planning Commission

- The City of Philadelphia’s Neighborhood Transformation Initiative (NIS), lead by Mayor John Street

Philadelphia’s Natural Resources

- Philadelphia’s city parks system

- Friends of the Wissahickon website, with information on the geology, soils, vegetation, wildlife habitats, and water quality of this valley in Fairmount Park

- Downloadable PDF brochures on Philadelphia’s native flora

- Philadelphia’s butterflies, from the Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center of the US Geological Survey

- Penn State Extension for Philadelphia, with information on soil testing, plant cultivation, and the Penn State Urban Gardening Program

Winners

Phase Two Grand Prize ($10,000)

Waterwork

Charles Loomi Chariss McAfee Architects: Chariss McAfee, Charles Loomis, Juliet Geldi and Gavin Riggall of KieranTimberlake Associates

Philadelphia, PA

The team proposes a strategy to Van Alen Institute. City Parks Association reclaim vacant sites throughout Philadelphia by recreating them as public green filters by capturing and redirecting water flow. This design strategy offers ecologically sound recreational and infiltration solutions for the use of naturally cleaned storm-water run-off. Waterwork proposes physical solutions at both a microscale and a macro scale. Waterwork incorporates a system to capture water on all the houses in a neighborhood and also proposes using existing city transit systems; railways and roadbeds, as sites for new underground gravel cisterns and byways. This would create and activate new urban streams, community spray parks and new biking and pedestrian trails. Radical in the simplicity of its premise, Waterwork illustrates groundbreaking and poetic ideas that add social and economic value to urban watershed. Resonant of Philadelphia’s industrial water-based past, Waterwork reinvents the precious symbiotic relationship water and cities once had. “The Urban Voids competition has asked an ecological question, a sociological question, an economic question and a built-environment and governance question,” said Carl Anthony, Program Director, Sustainable Metropolitan Communities Initiative at the Ford Foundation and a judge. “The winning project, Waterwork deals with all these issues; with social reality, a sense of the ecological story of water, a sense of the built environment, infrastructure and so forth. The beauty of Waterwork is that it beautifully recaptures the value of the hydrological cycle that in the 19th century drove the industrialization of our cities, including Philadelphia. This project has potential application in a lot of places that would actually move an agenda.”

Finalist ($5,000)

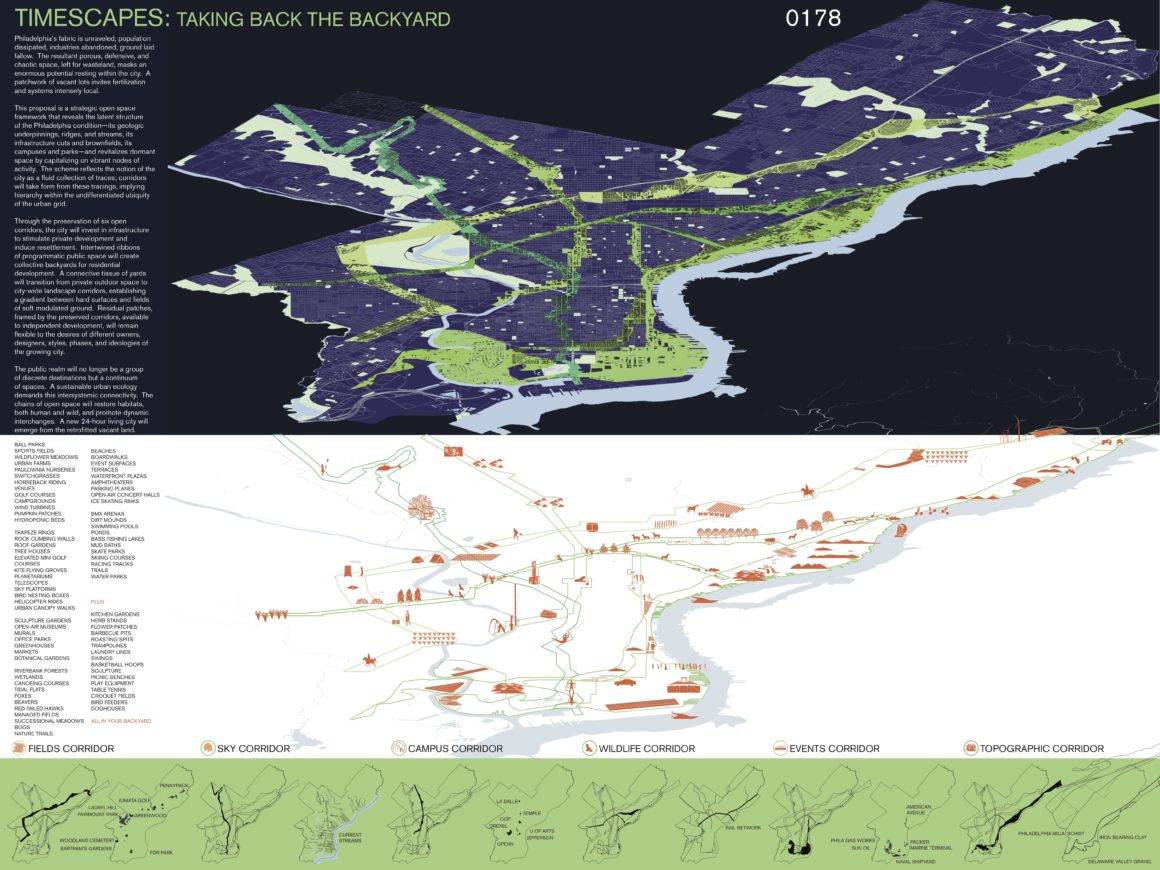

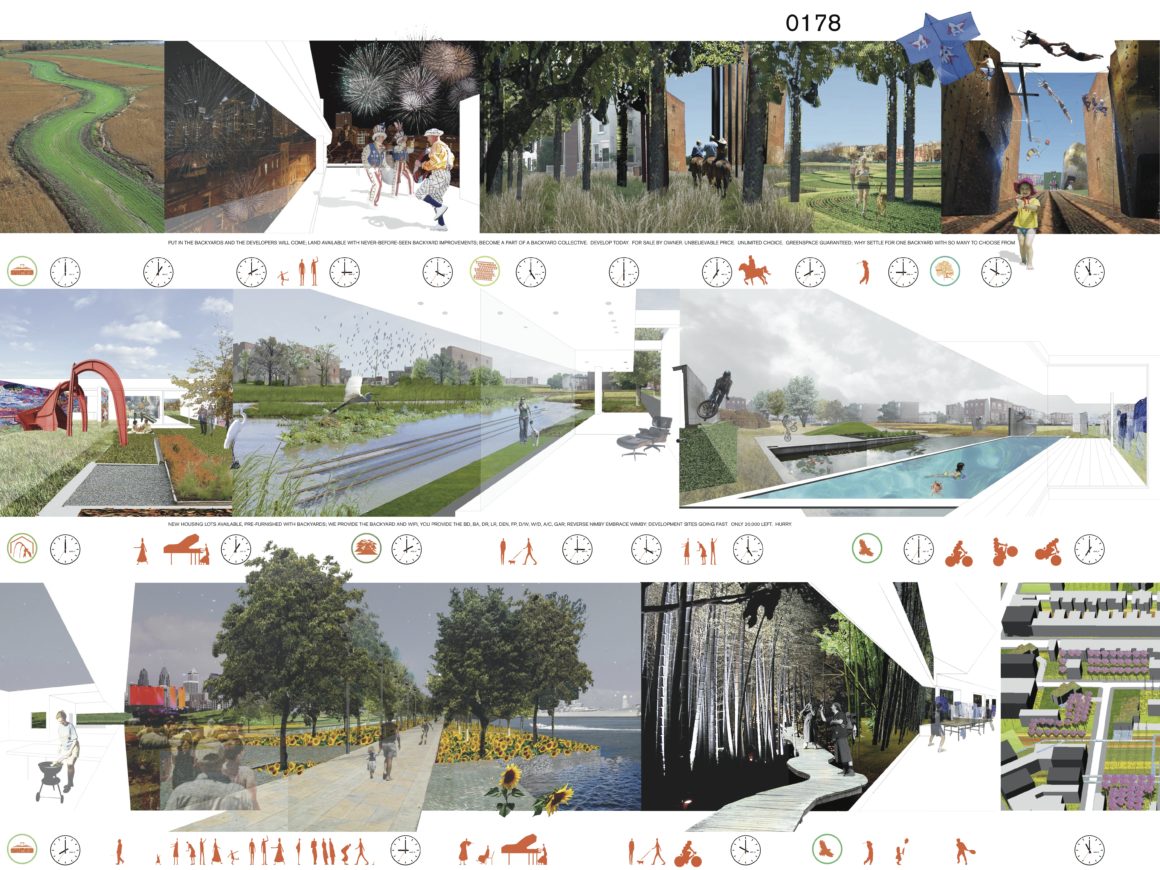

Timescapes: Taking Back the Backyard

Jill Desimini and Danilo Martic

Philadelphia, PA

Philadelphia’s fabric is unraveled, population dissipated, industries abandoned, ground laid fallow. The resultant porous, defensive, and chaotic space, left for wasteland, masks an enormous potential resting within the city. A patchwork of vacant lots invites fertilization and systems intensely local. This proposal is a strategic open space framework that reveals the latent structure of the Philadelphia condition—its geologic underpinnings, ridges, and streams, its infrastructure cuts and brownfields, its campuses and parks—and revitalizes dormant space by capitalizing on vibrant nodes of activity. The scheme reflects the notion of the city as a fluid collection of traces; corridors will take form from these tracings, implying hierarchy within the undifferentiated ubiquity of the urban grid. Through the preservation of six open corridors, the city will invest in infrastructure to stimulate private development and induce resettlement. Intertwined ribbons of programmatic public space will create collective backyards for residential development. A connective tissue of yards will transition from private outdoor space to city-wide landscape corridors, establishing a gradient between hard surfaces and fields of soft modulated ground. Residual patches, framed by the preserved corridors, available to independent development, will remain flexible to the desires of different owners, designers, styles, phases, and ideologies of the growing city. The public realm will no longer be a group of discrete destinations but a continuum of spaces. A sustainable urban ecology demands this intersystemic connectivity. The chains of open space will restore habitats, both human and wild, and promote dynamic interchanges. A new 24-hour living city will emerge from the retrofitted vacant land.

Finalist ($5,000)

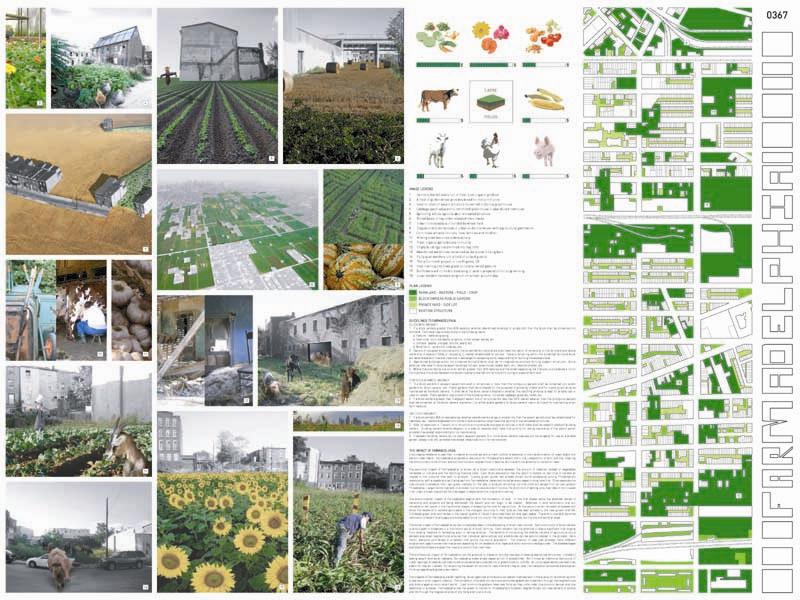

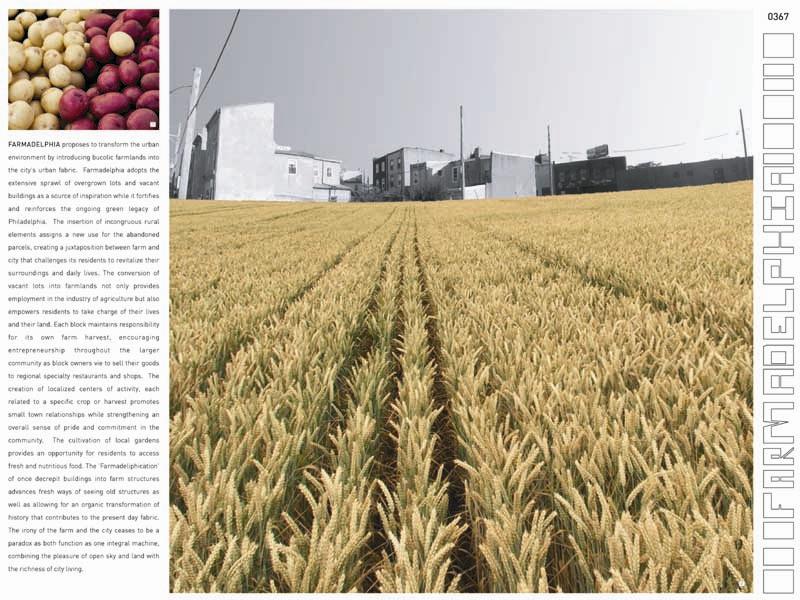

Farmadelphia

Front Studio: Yen Ha, Ostap Rudakevych, and Michi Yanagishita

New York, NY

FARMADELPHIA proposes to transform the urban environment by introducing bucolic farmlands into the city’s urban fabric. Farmadelphia adopts the extensive sprawl of overgrown lots and vacant buildings as a source of inspiration while it fortifies and reinforces the ongoing green legacy of Philadelphia. The insertion of incongruous rural elements assigns a new use for the abandoned parcels, creating a juxtaposition between farm and city that challenges its residents to revitalize their surroundings and daily lives. The conversion of vacant lots into farmlands not only provides employment in the industry of agriculture but also empowers residents to take charge of their lives and their land. Each block maintains responsibility for its own farm harvest, encouraging entrepreneurship throughout the larger community as block owners vie to sell their goods to regional specialty restaurants and shops. The creation of localized centers of activity, each related to a specific crop or harvest promotes small town relationships while strengthening an overall sense of pride and commitment in the community. The cultivation of local gardens provides an opportunity for residents to access fresh and nutritious food. The ‘Farmadeliphication’ of once decrepit buildings into farm structures advances fresh ways of seeing old structures as well as allowing for an organic transformation of history that contributes to the present day fabric. The irony of the farm and the city ceases to be a paradox as both function as one integral machine, combining the pleasure of open sky and land with the richness of city living.

Finalist ($5,000)

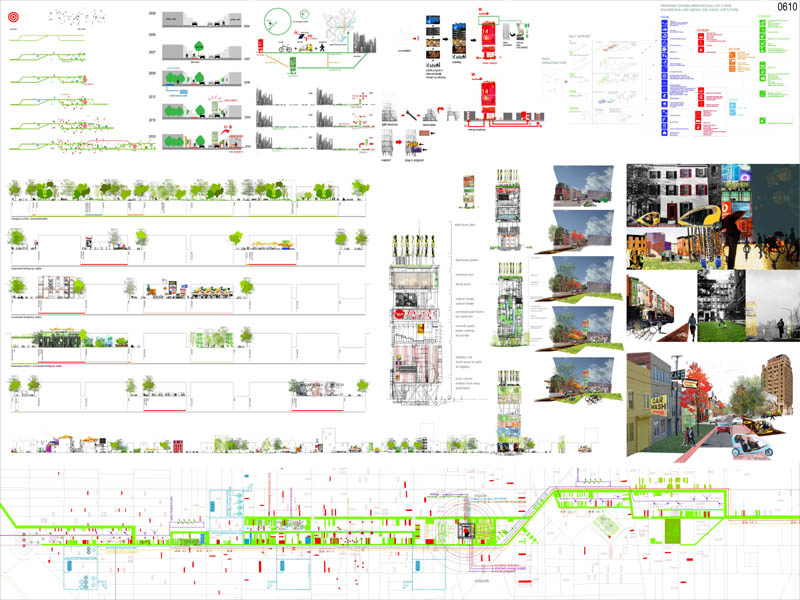

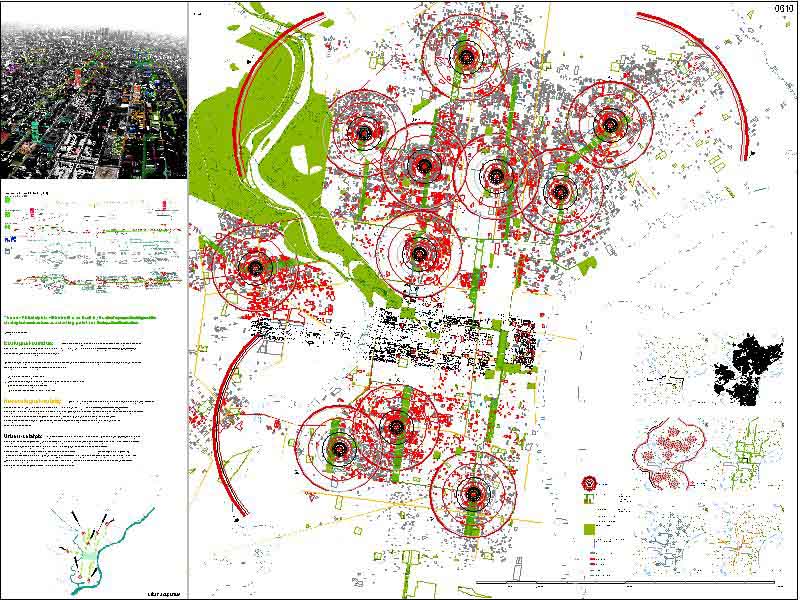

Ecological Corridors

Ecosistema Urbano Architects Ltd

Belinda Tato, Jose Luis Vallejo, Constantino Hurtado, Elena Prieto

Madrid, Spain

The new Philadelphia will be built over itself by its citizens. Our proposal intends to generate the strategical mechanisms as a starting point for the self reparation of the urban tissue.

Strategical concepts:

Ecological-corridors: Intervention strategy based on the concentration of budget and effort on a structural-line of program and activity. They will connect high percentage urban-void areas with Downtown, creating new connections with the existing green areas network.

A series of low-budget interventions on the selected streets will characterize the ecological-corridors-network and will become the engine to start the urban-regeneration of Philadelphia:

- Bicycle-lane limited by a tree-lane.

- Green-spaces-network linked by the ecological-corridor in urban-voids.

- Reconstitution of the original streams

- Basic improvement of available-urban-lots

New-ecological-mobility: Actual Philly has got an extense bicycle-lane-network and a growing interest to promote this way of transportation. The new-Philly-urban-landscape will be characterised by a new-generation of ecological-vehicles (technologized-velo-taxis, bicycles…) that will be used through the ecological-corridors making possible fast and customized connections between urban-catalysts and Downtown and creating link points with the existing-transportation-network. A secondary street order with existing or proposed bicycle-lane will ensure transversal-connections.

Urban-catalysts: dynamizer-focus of Philadelphia-urban-scene. Connected with Downtown through the ecological-corridors-network, they will be estrategically placed in areas with high percentage of urban-voids, at time-distance linked to the new-ecological-mobility-plan (6 min. velo-taxi).

It will become a concentrator of the democratically-elected-programms by the citizens of Philadelphia (Philadelphia-Land-visions) Light and dismantable structure. Renewal-energy-generator for supplying and strengthening the surrounding urban-voids. Once the healing duty has been complished the urban-catalyst can be dismantled and placed somewhere else at the ecological-corridors-network that requires a reactivation-process.

Finalist ($5,000)

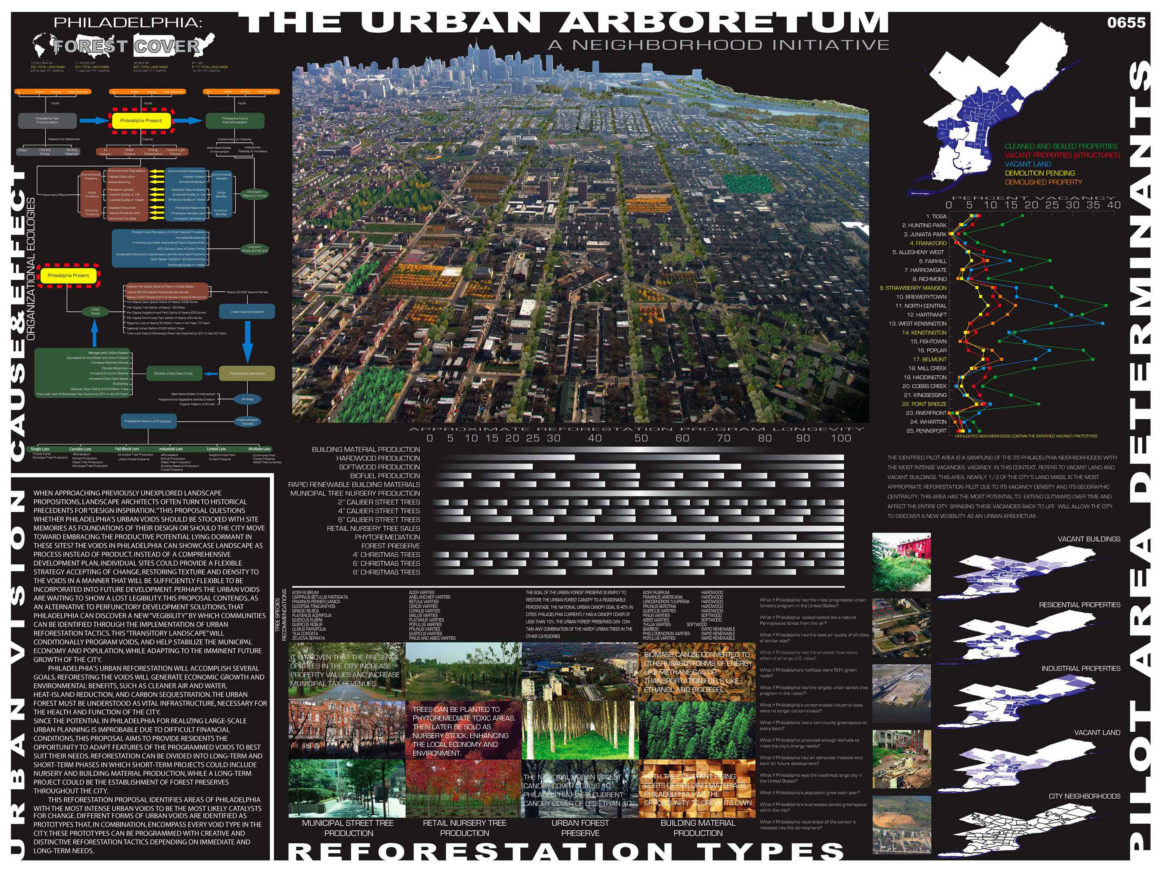

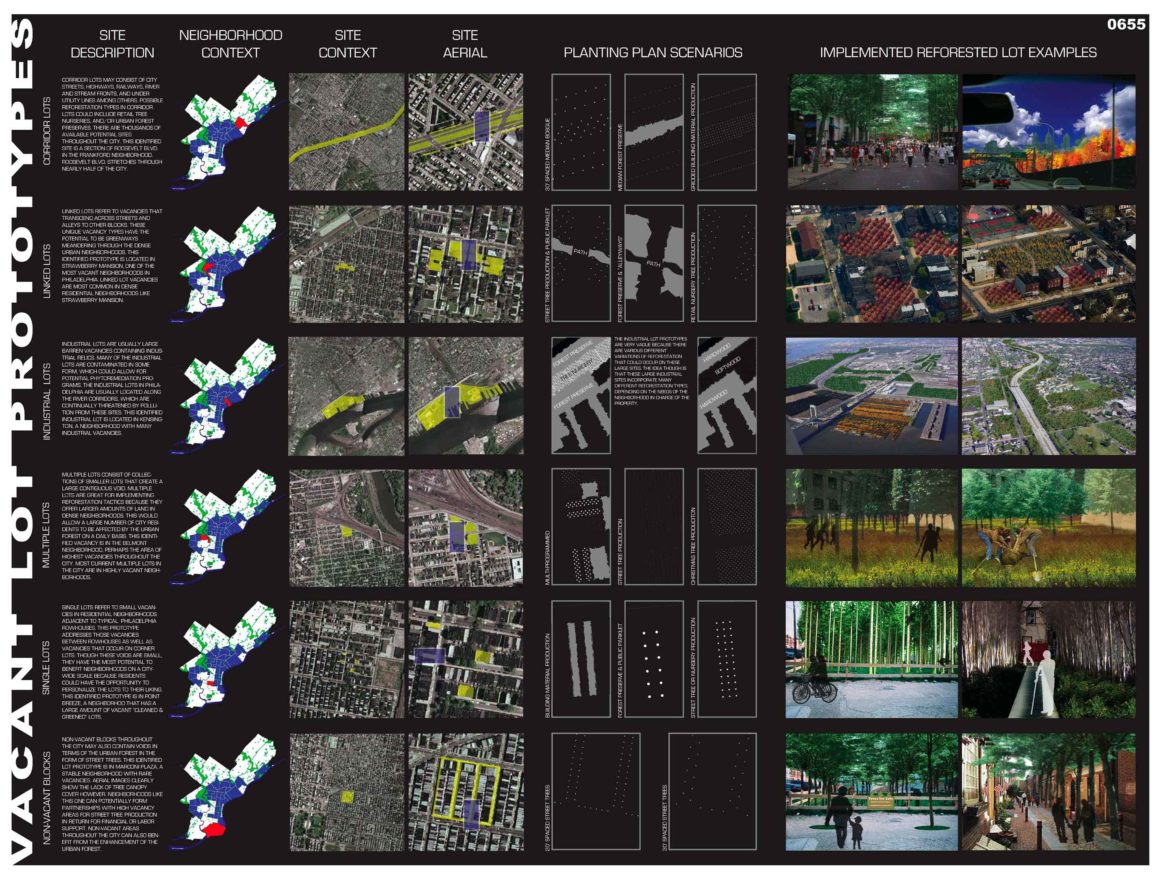

Urban Arboretum

Matthew Langan

Advisor Gale Fulton

University Park, Pennsylvania

When approaching previously unexplored landscape propositions, landscape architects often turn to historical precedents for “design inspiration.” This proposal questions whether Philadelphia’s urban voids should be stocked with site memories as foundations of their design or should the city move toward embracing the productive potential lying dormant in these sites? Instead of a comprehensive development plan, individual sites could provide a flexible strategy accepting of change, restoring texture and density to the voids in a manner that will be sufficiently flexible to be incorporated into future development. This proposal contends, as an alternative to perfunctory development solutions, that Philadelphia can discover a new “vegibility” by which communities can be identified through the implementation of urban reforestation tactics. This “transitory landscape” will conditionally program voids, and help stabilize the municipal economy and population, while adapting to the imminent future growth of the city.

Philadelphia’s urban reforestation will accomplish several goals. Reforesting the voids will generate economic growth and environmental benefits, such as cleaner air and water, heat-island reduction, and carbon sequestration. Since the potential in Philadelphia for realizing large-scale urban planning is improbable due to difficult financial conditions, this proposal aims to provide residents the opportunity to adapt features of the programmed voids to best suit their needs. This reforestation proposal identifies areas of Philadelphia with the most intense urban voids to be the most likely catalysts for change. Different forms of urban voids are identified as prototypes that, in any combination, encompass every void type in the city. These prototypes can be programmed with creative and distinctive reforestation tactics depending on immediate and long-term needs of each Philadelphia neighborhood.

PHASE ONE HONORABLE MENTION

Felipe Ariza and Ana Maria Alvarez (Barcelona, Spain)

Elizade/Gomensoro Architects: Leonardo Elizade, Nguyen

Gomensoro, Ximena Silveira, Francisco Nader, Ignaci

Percovich (Montevideo, Uruguay)

Andries Geerse Stedenbouwkundige: Andries Geerse, Johan

De Wachter, Mathias Madaus, Job Lee, Laura Gracia, Alexandra Waluda, Ludvig Netre (Rotterdam, TheNetherlands)

Interboro: Georgeen Theodore, Tobis Armbost, Daniel D’Oca (Brooklyn, NY)

Loop | 8: Christopher Marcinkoski, Andrew Moddrell and Dartagnan Brown (Larchmont, NY)

Image Gallery

Resources

Sponsors

The City of Philadelphia Office of Housing and Community Development

The Claneil Foundation

The National Endowment for the Arts

The Samuel S. Fels Fund

Partners and Collaborators

City Parks Association of Philadelphia

Penn Horticultural Society

Penn Environmental Council

The Reinvestment Fund

For more information visit:

City Parks Association (CPA) of Philadelphia