About

National Parks Now was a competition inviting multidisciplinary teams of young professionals to develop strategies for reshaping the national parks visitor experience.

As the National Park Service prepared to celebrate its centennial in 2016, the competition highlighted four parks in the Northeast Region as case studies for attracting diverse audiences, telling new stories, and engaging the next generation of visitors at a time of fast-evolving technologies, regional contexts, and audience expectations. The National Parks Now sites tell complex stories about one of the country’s densest and most diverse urban regions, containing countless layers of the nation’s economic, ecological, and cultural history.

National Parks Now called on teams to propose a broad range of interventions—new learning tools, hands-on workshops, customizable self-led tours, site-specific leisure and exploration opportunities, digital narratives, short or long-term interactive installations, performance events, outreach and engagement campaigns, for example—to create new experiences that connect these parks to larger, more diverse audiences throughout the region, and develop a model for similar parks nationwide.

Drawing together professionals from the fields of architecture and landscape architecture, graphic and interactive design, exhibition and film production, history, preservation, communications, and the social and environmental sciences, teams explored how these parks could provide opportunities for reflection, recreation, and learning; identify partnerships and ventures that could transform visitors into stewards and ambassadors; and re-imagine how historic sites can respond to changing demographics and technologies. At a time of limited park resources and budgets, new ideas and strategies are needed to ensure these sites’ relevance and long-term sustainability, and to attract larger, increasingly diverse audiences that have countless opportunities for how they are entertained, educated, and engaged in the world around them.

By focusing not on capital projects that require huge investments of time and resources but rather calling for a nimbler range of engagement, outreach, and experiential strategies, National Parks Now provided an opportunity for teams to truly push the boundaries of what national parks can be in the 21st century.

As the teams developed their proposals and pilots, VAI distilled six ‘Great Ideas’ emerging from each of the teams that can guide NPS as well as municipalities, advocates, and others who are invested in the future of parks, historic sites, managed landscapes, and many other types of landscapes. View the ideas and information about the four sites, finalist teams, and proposals.

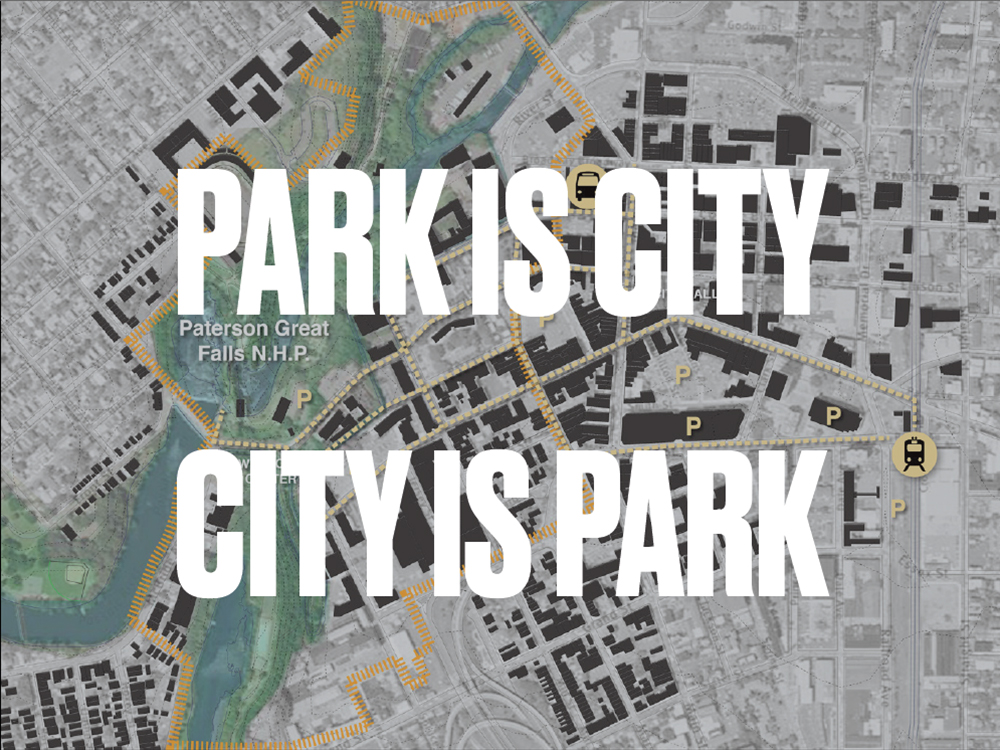

It’s no accident that people often refer to urban parks as a common “living room” for its users: the parks we love are extensions of the communities and places where we feel at home. One way to foster this sense of ownership for any given park is to blur the boundaries between what is and isn’t the park – to let our experiences and routines and emotional attachments for the surrounding streets, hangouts, and neighborhoods spill into the park, and vice versa. Both the park and its surrounding areas then become more accessible to people who might have ignored one or the other.

With its many recent immigrant communities, Paterson has become a hub for restaurants and food from around the world. Team Paterson’s project proposes ongoing food-related programming that establishes long-term partnerships between the park and community restaurants. For example, the team will brand common restaurant items – such as take-out bags and placemats – with the slogan “Great Falls, Great Food, Great Stories,” creating relevant associations between the park and the diverse cultural traditions and histories existing nearby. The team also developed eye-catching wayfinding and social media campaigns that highlight the proximity of the park to popular restaurants on Paterson’s Market Street, encouraging partnerships between restaurant owners and NPS staff.

The national parks were founded on an idea that the country’s parkland could be a critical resource for a democratic society. Today, the National Park Service has a tremendous opportunity to lead conversations about pressing cultural, ecological, and social issues such as climate change and water conservation. The Steamtown team developed a methodology that would help National Historic Sites across the country explore nationally and globally significant issues and themes by building on their existing, core narratives.

At Steamtown, for instance, through the lens of steam technology, visitors could debate or ponder the future of energy, economic development prospects for formerly industrial cities, and new models for educating future leaders in science and engineering. Through its sites across the country, and its outreach in diverse communities throughout American society, the National Park Service ultimately could be seen as a leader in addressing complex issues that will shape the nation’s future.

Park wayfinding systems are designed to guide and inform people, but sometimes these systems demand too much of our attention. Visitors spend their time in a park staring at apps and maps instead of the world around them.

The Weir Farm team created a flexible system of lightweight devices that can be placed in the landscape to encourage visitors to focus their attention on light, color, and ecology, phenomena that were central to the work and life of the artist who established the site. For instance, a series of simple viewpoles train the visitors’ eye on details of seasonal foliage or the specific hue of a winter sky.

Visitors are then encouraged to photograph and share these views online, creating a composite record of the site. The team also developed a Mowing Guide that reimagines the park’s existing maintenance regime of open spaces to create new pathways and gathering spaces that connect different habitat zones or transitions from historic to contemporary landscapes.

By subtly directing visitors to discover and pay attention to the landscape, while keeping a low-profile, these tools and practices promise visitors a rare escape from our usual state of infinite distractions.

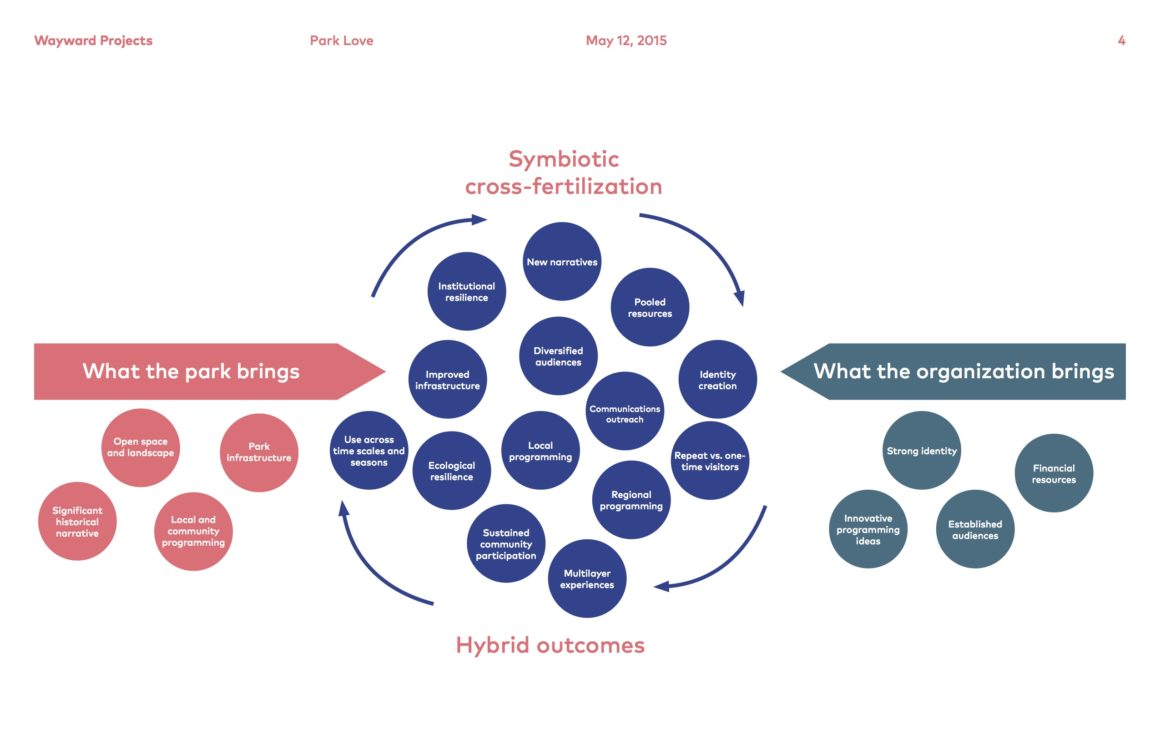

Parks need good partners, especially in an era of budget and staffing constraints. Partners bring users, advocates, and stewards; generate ideas about new programs and experiences; and can open doors to new funding or other resources. But as with any relationship, it’s not easy to find people and organizations who’d be a good match, or to develop mutually beneficial working relationships that can be sustained.

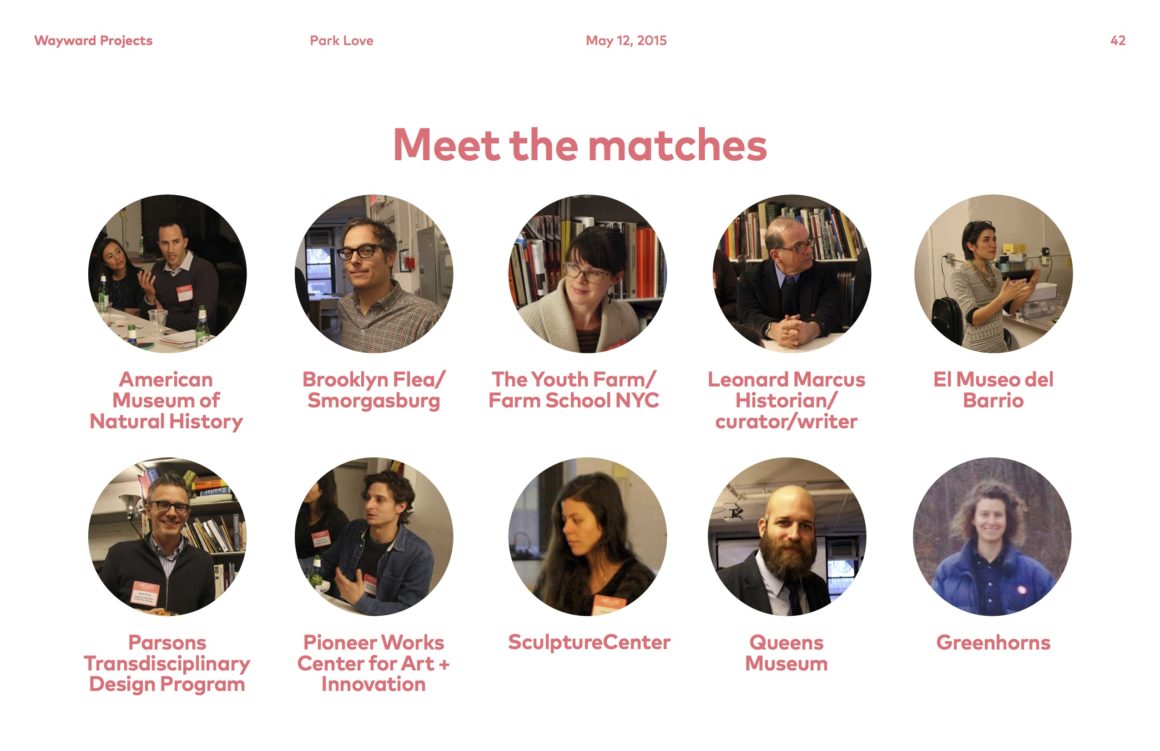

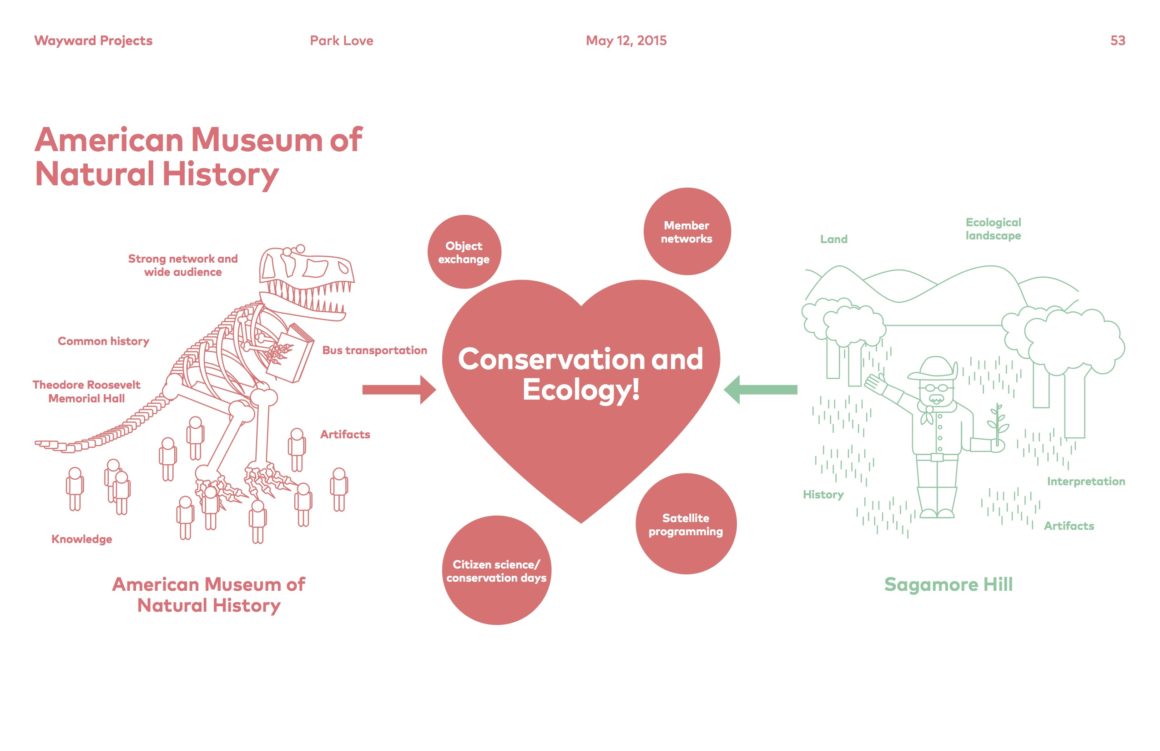

Enter a matchmaker – in this case, the Sagamore Hill team, which developed a playful methodology for the serious business of developing new cultural partnerships for the park. Imagining the Sagamore Hill National Historic Site as an eligible bachelor looking for love, the team organized a Date Night (complete with wine and romantic lighting) that brought park staff together representatives from regional urban farms, museums, graduate design programs, and other organizations to meet and talk about potential collaborations. The most promising matches were invited back for a second date to develop a pilot project:

This innovative framework made the partnering process easier for park staff – at an individual level, the matchmaking metaphor provided a fun, disarming way to break the ice and free people to imagine unconventional ways of working together. At the organizational level, the framework allowed park staff to meet potential partners outside of their usual circles and develop new program possibilities.

Every city contains countless complex stories about our nation’s history, and about the ways we understood and experienced our economy, nature, and technology at different points in time. We return to these stories in order to remember how we got here, and what that might mean about where we’re going. But how do you tell a 250-year old story in a way that matters to a 25-year old? How do you capture that history in a way that’s engaging to people, and that draws on lessons from the past to help point the way in the future? Find a hook that’s relevant for today. Add visuals. Tell it in many languages.

That’s how the Paterson team approached the challenge of reaching contemporary audiences with the many layers of political, ecological, and cultural history at Paterson Great Falls. The team produced large posters featuring sound bites translated into Arabic, Spanish and other languages from key moments in and around the park (a picnic held by Alexander Hamilton and other Founding Fathers, a snippet of an epic poem about Paterson referencing the active factories that once lined the Passaic River, stories from the city’s multi-layered immigration history), remixing these narratives to speak to current events and populations from around the world. These posters, which can be adapted to any kind of narrative, become a portal that reveals multiple layers of history at one time.

Parks make great classrooms – they offer opportunities for hands-on, immersive learning that cuts across conventional boundaries of a Math, History, or Science class. Educational programs in parks don’t need to be expensive affairs – they can draw on the expertise of park employees, volunteers, or a network of professionals whose work intersects key themes that the park enables visitors to explore. Historic sites like the four parks in National Parks Now have a particularly rich trove of material that can engage students and people of any age.

The team at Steamtown proposed incorporating the S.T.E.A.M. curriculum into the park’s programming, referring to the K-12 curriculum that offers a multidisciplinary approach to learning through Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Math. For its pilot project, the team designed a one-day workshop that introduces young people to principles of design and manufacturing, while exploring themes such as the future of transport. The team brought together representatives from local universities, the public school system, and Maker organizations to develop educational programs that will introduce young people in Scranton to potential career paths. At a broader scale, this strategy ties NPS to a national education agenda, and offers a replicable model for engaging communities around active learning.

COMPETITION WINNER:

Team Paterson

Led by Manuel Miranda of MMP and the Yale School of Art with Frances Medina, Mariana Mogilevich, Valeria Mogilevich, June Williamson, and Willy Wong, the winning team, Team Paterson, imagined the park and the city as extensions of each other, connecting Great Falls to immigrant communities and their local restaurants in the surrounding neighborhoods. Their project “Great Falls, Great Food, Great Stories” ties the historic narratives that the park explores with the stories and diverse, cultural traditions of local residents. The team’s pilot culminates in a tour led by park rangers that extends beyond the park to include local restaurants, and a communal meal at the park catered by local restaurants. The project blurs these boundaries by establishing ongoing food-related programming for restaurant owners and the park. For instance, the restaurant owners participating in this pilot have agreed to collaborate in the Taste of Paterson food festival to be held at the Falls in summer 2016.

About the Site

Paterson Great Falls is perhaps the only national park that inspires advocates to describe it proudly as both an “urban oasis” and “gritty.” It is also one of the newest national parks in the country, having been established in 2011. These factors make it an ideal case study for the future of urban national parks, and the ways that these sites can serve as both a respite from and a deeply embedded part of the city.

The park is centered around a 77-foot waterfall, but for many people the visitor experience extends along Market Street, a colorful, mile-long stretch of Peruvian restaurants, small stores, and civic buildings that connects the Falls to downtown Paterson, and from there, the region (including New York City, via a 40-minute ride on New Jersey Transit). Park advocates are eager to expand the conceptual borders of the park to encompass the broader communities and narratives of the city and the region.

Once ranked by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development as the most economically distressed city in America, Paterson is now gaining population. As was true historically, when immigrants from around the world worked the city’s mills, Paterson today is home to a diverse population – more than half of the city’s 150,000 residents, for instance, are Latino. Initiatives such as the Great Falls Youth Corps program, which hires local teenagers to give guided tours of the park and perform maintenance, provide a great model for how the park can attract young people from many different backgrounds to become stewards and ambassadors for the park, while finding echoes of their own story in the city’s immigrant history.

Renovations and long-range planning at the park are still ongoing. Later this year, a renovated area of the park will open offering enhanced views of the falls and passive recreation, and a newly-rehabilitated Welcome Center and store will serve visitors. Other areas of the park – including the eastern end, occupied by the massive ruins of a former printing plant – remain closed to the public. This sense of a site and identity still being defined offers a unique opportunity to include new narratives, audiences, and approaches in the park’s development.

COMPETITION WINNER:

Team Wayward / Projects

Team Wayward / Projects is a collaboration between the landscape, architecture and art practice Wayward (London) and graphic design studio, Project Projects (New York). The team is led by Prem Krishnamurthy, Amy Seek Putri Trisulo, Heather Ring, and Shannon Harvey. The team developed and implemented a ‘matchmaking’ methodology (complete with a dating profile for the park) that helped set up the park on a first date with unexpected potential partners in order to develop entirely new programming opportunities. The proposed pilot is a one-day Summit addressing a topic of national and global importance, building on Roosevelt’s legacy of engaging with national dialogues from his estate.

About the Site

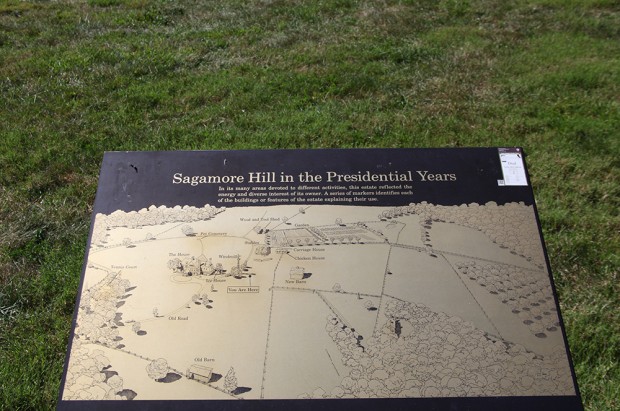

Theodore Roosevelt was a larger-than-life figure with deep ties to the New York region. He served as New York City’s Police Commissioner and Governor of New York State, and as the nation’s 26th President he established a “Summer White House” at his Sagamore Hill estate on the north shore of Long Island. Roosevelt originally purchased the land as a refuge from city life, but ultimately it became his permanent home, and a seat of American power and history.

Roosevelt’s house has always been the centerpiece of the 83-acre Sagamore Hill National Historic Site. With the house closed for renovations until 2015, park staff have the perfect opportunity to reconsider the site as a whole, and how new themes, programs, and activities can encourage people to depart from Roosevelt’s story to create their own experiences within the landscape.

From the house, a short walk on one of the site’s nature trails leads to a salt marsh, where park staff offer hands-on wildlife workshops and coastal ecologists regularly conduct research. Staff hope to explore partnerships with other environmental experts and to create new citizen science programs, which are increasingly relevant to a landscape vulnerable to climate change and rising sea levels. However, not all new uses of the site will be so straightforward. For instance, Roosevelt championed strenuous physical activity, including long walks around Sagamore Hill in which he famously insisted on clambering over, under, or through any obstacles in his path. Park regulations, however, prohibit most forms of active recreation (though local dog walkers have found a haven in the rambling grounds).

During warm months, park staff sometimes turn away visitors from guided tours that are over-capacity, and lack facilities to accommodate outdoor events for more than a dozen or so people. Creating more self-directed visitor experiences would help alleviate this problem. Yet this space constraint, which forces park staff to partner with organizations in town to host off-site events, also suggests new opportunities to bring the narratives embedded in Sagamore Hill to audiences throughout the region, especially underserved populations that otherwise might not be able to travel to the site itself.

COMPETITION WINNER:

Team FORGE

Led by Abigail Smith-Hanby of FORGE with Ashley Ludwig, Andrew Dawson, Max Lozach, and CJ Gardella, Team FORGE proposed incorporating the S.T.E.A.M. curriculum into the park’s programming, tying the history of making trains at Steamtown to the modern Maker Movement in efforts to connect the park’s narrative to more diverse, younger audiences, and as well as to educational curricula. The pilot is a one-day workshop with local students who will learn welding and other manufacturing techniques, and explore modern transportation through a DIY electronics workshop.

About the Site

Steamtown National Historic Site is a mecca for trains, particularly the steam locomotives that dominated the American landscape for a hundred years through 1950. The sheer size and physicality of the trains themselves (as well as the heavy machinery and cavernous warehouses used to maintain them) represent the best of “living history”: they are relics of the past that you can still ride or watch being operated, and which evoke a visceral sense of cultural, technological, and social history.

Park staff and local stakeholders are actively exploring new partnerships and package tours that could draw new visitors from throughout the region. Yet ironically, some of the opportunities to make better connections to broader audiences come from new programs and initiatives that do not focus on trains.

Steamtown is located in the heart of Scranton. Search for the park on Google Maps, however, and you’ll be directed to the parking lots of the Mall at Steamtown. The mall happens to provide pedestrian access to the park: it’s an odd juxtaposition that suggests a new kind of 21st century gateway from the park into people’s lives that could make the park an everyday resource and public space for Scranton, and could help facilitate its recovery from decades of economic disinvestment.

NPS staff practicing traditional and historic trades in Steamtown’s active repair shops work with a wide range of volunteers, including retired engineers, students from the nearby University of Scranton, and others from extremely diverse backgrounds. These relationships could extend to new apprenticeships or skillshare programs, or attract artisans of many kinds who are helping to create a contemporary renaissance of making. The park’s theater could host lectures, performances, and other events that address new technologies, subcultures, and other topics relating in some way to Steamtown’s legacy.

One of the exhibits at the park’s history museum describes how the rail lines at the turn of the 20th century realized they had to create new associations and experiences for the public in order to attract customers to ride trains more than once. Similar challenges and opportunities face those seeking to ensure Steamtown’s relevancy in the 21st century.

COMPETITION WINNER:

Team Weir

Led by Aaron Forrest of the Rhode Island School of Design and Principal of Ultramoderne with Yasmin Vobis, Suzanne Mathew, Noah Klersfeld, Dungjai Pungauthaikan, and Jessica Forrest, Team Weir devised a series of wayfinding techniques that encourage visitors to guide themselves around the park and to focus their attention on light, color, and other natural phenomena. For their pilot, the team constructed a set of viewpoles to be distributed throughout the site, encouraging visitors to look closer at the landscape. The park plans to redistribute the viewpoles at different points throughout the course of the year with the help of their resident curator, highlighting elements of the landscape each season.

About the site

Weir Farm National Historic Site celebrates the legacy of American artist Julian Alden Weir (1852-1919), considered the founder of American Impressionist painting. Of the more than 400 national parks, Weir Farm is the only one dedicated to painting, and one of only two to host a year-round Artist-in-Residence program. It may seem strange, then, that the park’s staff has dedicated themselves to answering the question: Why should anyone care about American Impressionism?

Weir Farm interprets that question broadly, using elements of art-making and nature – light, color, escape, reinvention – as touchstones to create memorable personal experiences and unexpected connections. Recently, for instance, Yale Medical School proposed sending students to Weir Farm to hone their senses and train their powers of perception to better identify symptoms in their patients. Park staff have expressed interest in NPS’ Healthy Parks Healthy Peopleinitiative, in which participating medical practitioners write prescriptions to visit national parks to improve public health outcomes.

Weir himself used the site as a retreat from his home on East 12th Street in New York and from the demands of the city’s arts world. Though big cities are typically thought of as a realm for people to re-invent themselves, Weir looked to his summer estate as a safe place to experiment and take risks. Today, the park still has this potential to encourage personal exploration through escape – whether it’s inner city Girl Scouts seeking a refuge to address bullying, or individuals borrowing the free art supplies on offer at the park to try their hand at watercolors.

The park has seen a significant increase in visitors this year with the opening of Weir’s home, studio, sculpture studio to visitors for the first time in the park’s 25-year history. Yet park staff insist they are not interested in simply boosting visitation numbers. Rather, the challenge is to continue to create innovative, self-directed, high-quality experiences despite constrained budgets and staff resources. National Parks Now will dovetail with a parallel NPS initiative to plan and design exhibits throughout Weir Farm, focusing on multisensory elements (for example, opportunities to smell the paint and mineral spirits Weir used, or to hear the recorded voice of the artist).

Jurors

Glen Cummings, Partner, MTWTF

Fred Dust, Partner, IDEO

Shaun Eyring, Chief, Resource Planning and Compliance, Northeast Region, National Park Service

Mark Hansen, Director, Brown Institute for Media Innovation, Columbia University School of Journalism

Setha Low, Professor, Ph.D. programs in Anthropology, Geography, and Environmental Psychology, The Graduate Center, City University of New York

Emile Molin, Senior Design Manager / Creative Director at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

William Morrish, Dean, Parsons School of Constructed Environments

Kate Orff, Partner, SCAPE / Landscape Architecture

Barbara Pollarine, Chief, Interpretation, Education, and Partnership Development, Northeast Region, National Park Service

David van der Leer, Executive Director, Van Alen Institute