How could high-speed rail change American life in the coming decades?

About

Comprehensive high-speed rail has long been considered a pipe dream in the U.S. However, with the Obama administration’s 2011 pledge of $53 billion for the construction of a high-speed rail network, and its goal of connecting 80 percent of Americans to the service by 2050, the nation has taken the first steps towards a new era of physical connectivity.

Van Alen’s competition thrust designers’ ideas, narratives, and images into a national discussion that had previously been dominated solely by politics, and generated dozens of proposals for how to build this new infrastructure. Entrants envisioned the cultural, environmental, and economic impact of a new rail network for the nation’s communities, whether urban or rural, rail-riding or car-centric, heartland or borderland, in a new era of transportation connectivity. The resulting proposals, presented at museums, offices, and universities across the U.S., crystalized the hopes and fears associated with realizing this new infrastructure, and offered the public a glimpse of new ways of getting from A to B.

jurors

Advisory Committee:

> Carol Coletta, Director, ArtPlace

> Keller Easterling, Associate Professor, Yale University

> Christopher Hawthorne, Architecture Critic, Los Angeles Times

> Gary Hustwit, Director, Helvetica

> Michael Lejeune, Creative Director, L.A. Metro

> Thom Mayne, Founder & Design Director, Morphosis

> Petra Todorovich, Director, America 2050

> Sarah Whiting, Dean, Rice School of Architecture

PROJECT FELLOWS:

> Diana Lind & Andrew Colopy

GRAPHIC DESIGN:

The Beacon

MANIFESTO Architecture P.C.

New York, New York

The beacon is an icon not just for the city but for the megaregion, with a glowing presence forever amplified when reflected in the continuous growth of the city around it. Project Statement:

Chiland

Kent State University’s Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative (CUDC)

Cleveland, Ohio

Advisory Overview:

ChiLand takes its cue from aMad Magazine technique to animate the potential merging of distinct urban cultures.

Project Statement:

Life at the speed of rail redefines boundaries.

Distant cities are closer together, creating a new hybrid geography.

Employing a fold-in page technique popularized by Mad Magazine, the illustrative poster expresses the altered perception of distance and geography made possible by high speed rail. Chicago and Cleveland, two cities currently separated by six hours of highway driving, will be within two hours of each other for high speed rail passengers. This urban conjunction experience, ChilLand, opens possibilities for increased economic, social and cultural ties between the two cities. Football fans can tailgate (or “railgate”) on the train before a game at a rival’s stadium and return home safely, without the need to drive. As cities in the United States continue to face unprecedented challenges and uncertainty, high speed rail redefines the context for a more cooperative and shared future.

PROJECT TEAM: David Jurca, Gauri Torgalkar, Sagree Sharma, Terry Schwarz, Steve Rugare

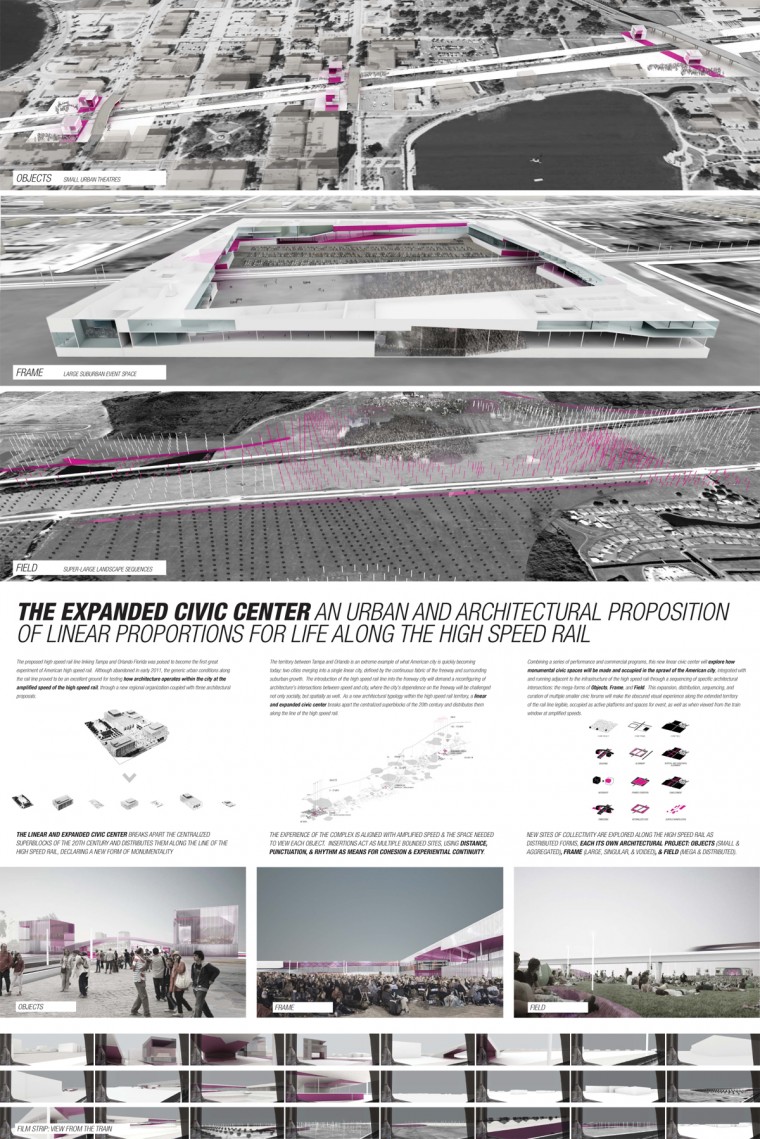

The Expanded Civic Center

Rebecca Sibley

Houston, Texas

Advisory Overview:

The Expanded Civic Center reconfigures 60’s mega-blocks for today’s mega-regions with a new set of mega-forms.

Project Statement:

The proposed high-speed rail line linking Tampa and Orlando Florida was poised to become the first great experiment of American high-speed rail. Although abandoned in early 2011, the generic urban conditions along the rail line proved to be an excellent ground for testing how architecture operates within the city at the amplified speed of the high speed rail, through a new regional organization coupled with three architectural proposals.

The territory between Tampa and Orlando is an extreme example of what American city is quickly becoming today: two cities merging into a single linear city, defined by the continuous fabric of the freeway and surrounding suburban growth. The introduction of the high speed rail line into the freeway city will demand a reconfiguring of architecture’s intersections between speed and city, where the city’s dependence on the freeway will be challenged not only socially, but spatially as well. As a new architectural typology within the high-speed rail territory, a linear and expanded civic center breaks apart the centralized superblocks of the 20th century and distributes them along the line of the high-speed rail.

Combining a series of performance and commercial programs, this new linear civic center will explore how monumental civic spaces will be made and occupied in the sprawl of the American city, integrated with and running adjacent to the infrastructure of the high speed rail through a sequencing of specific architectural intersections: the mega-forms of Objects, Frame, and Field. This expansion, distribution, sequencing, and curation of multiple smaller civic forums will make the obscured visual experience along the extended territory of the rail line legible, occupied as active platforms and spaces for event, as well as when viewed from the train window at amplified speeds.

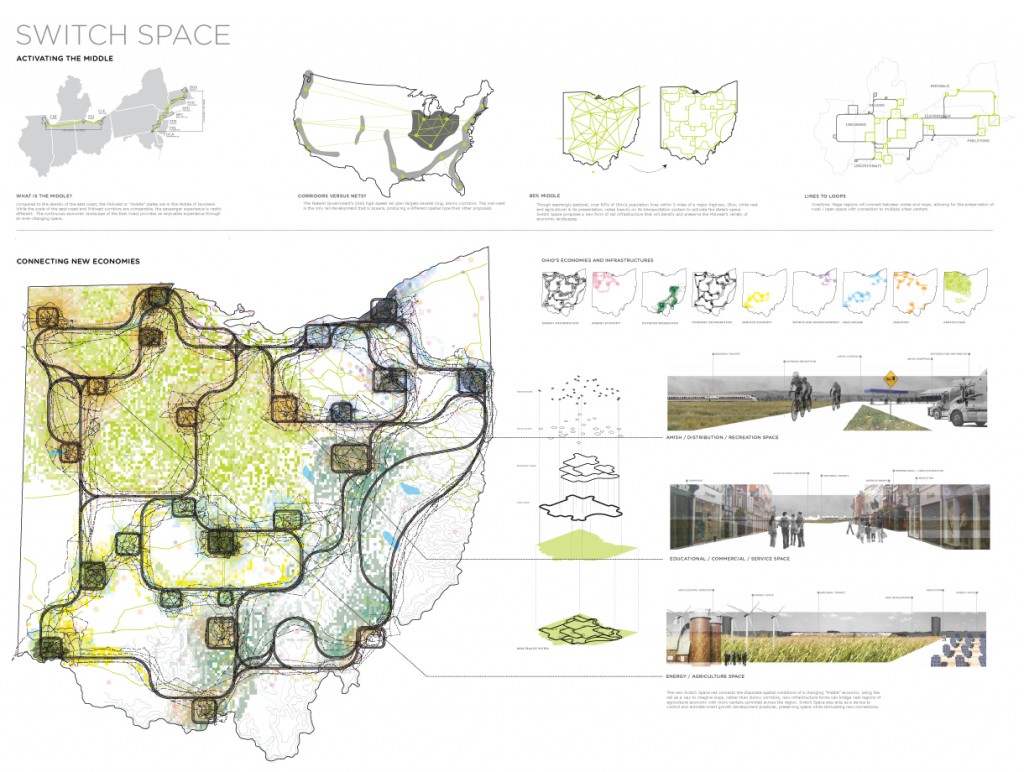

Switch Space

Karen Lewis, Emma Cuciurean-Zapan, Christine Yankel

Columbus, Ohio

Advisory Overview:

Switch Space questions the logic of linear corridors within the geography and development patterns of the Midwestern expanse.

Project Statement:

Switch Space envisions new forms of rail infrastructure that consider the Midwest’s disparate landscapes and economic geographies.

Most of the 2050 high-speed rail proposals focus on connecting dense urban corridors developed along regions bound by oceans, mountains or rivers. These long, skinny corridors are effective landscapes for density and development, ideal for high speed rail travel. The Midwest faces unique conditions. It is neither encumbered by these geomorphologies, nor do they benefit from their control. Rather than an infrastructure that responds to the corridor, the Midwest requires transit connections that work as a wide net, rather than a series of point-to-point connections.

Although it is vast and flat, the Midwest is deceptively urban. While 85 percent of Ohio’s landscape is census defined as “rural,” over 80 percent of its population reside within 10 miles of an urban core. The rural / urban connections extend to its economy as well. Ohio exports many agricultural products, but its economy is shifting to export wind energy and polymers, biotechnology, health care and education.

The new infrastructure of Switch Space addresses these changing landscapes, bridging rural spaces with urban centers, connecting agricultural economies with health care and education, and considering how high-speed rail and its supporting infrastructures can work together to connect and preserve the Midwestern landscape.

Permeable Response

Annie Kurtin, Laura Stedman

Tucson, Arizona

San Francisco, California

Advisory Overview:

Permeable Response confronts the ecological deterioration in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, an important resource for water and agriculture.

Project Statement:

The Sacramento – San Joaquin Delta located east of the San Francisco Bay in Northern California, has long been an important resource providing agricultural and recreational uses, wildlife habitat, infrastructure pathways, and water supply services throughout the state. This delta region is currently in crisis, with weakening levee structures and a deteriorating ecosystem due to rapidly increasing pollution levels.

Our proposal for a high-speed rail network in the region will rethink how architecture can become better integrated with large-scale infrastructure to improve the environment and people’s lives.

Our design produces an active permeable boundary whose function is three-fold: to transport pedestrian and cargo rail traffic between the San Francisco and Sacramento megaregion; support phyto-remediation and constructed wetlands where the bridge meets the water; and provide facilities for environmental research, pollutant testing and education.

The trains are elevated by a structural system that provides flexible spaces for program in the form of hanging research labs and infill educational facilities. These public facilities are accessible from the transportation terminals. In order to meet the water as lightly as possible, the supporting trusses are designed using steel instead of bulkier concrete columns.

Constructed wetlands grown at the base of this new high-speed rail bridge respond to varying pollution levels, becoming a living barometer of water health. The reeds serve to filter the water, help stabilize the land, and encourage native species to return. Our project is designed to grow over time while responding to, and engaging with, the dynamic Sacramento – San Joaquin Delta waterscape.

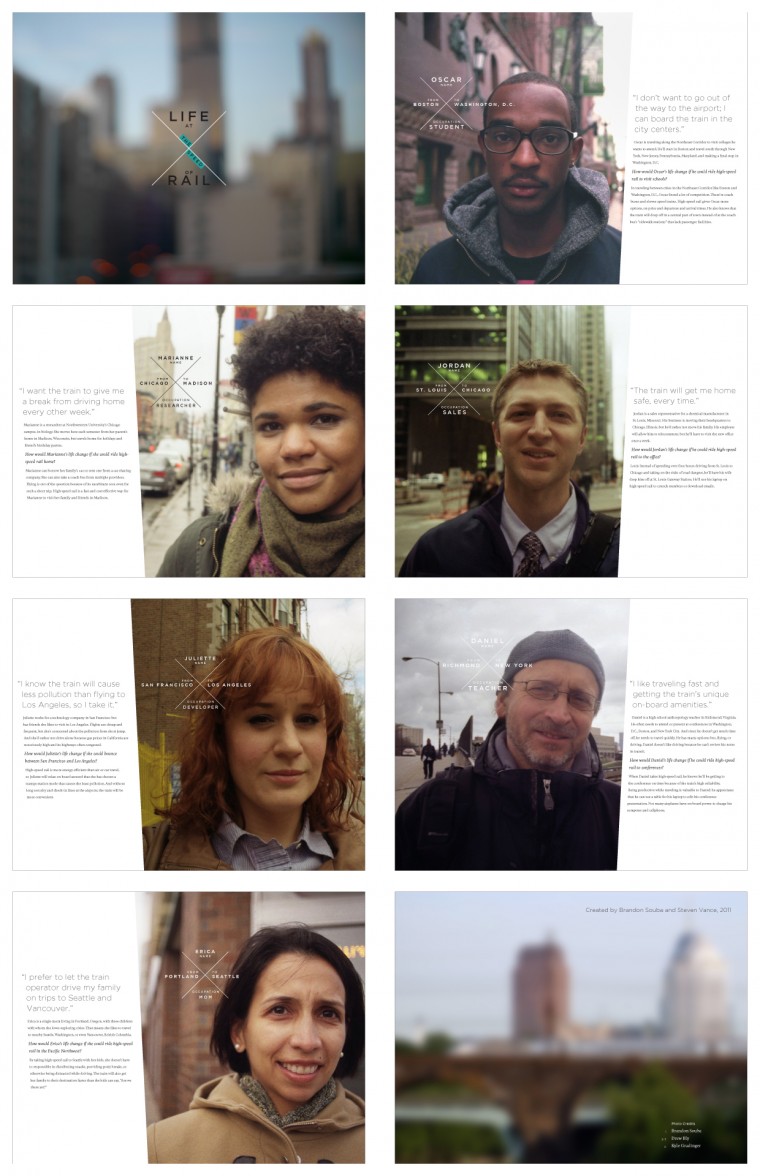

Drew Bly, Brandon Souba, Steven Vance

Chicago, Illinois

Advisory Overview:

The Effect of High-Speed Rail on Six Lives proposes an ad campaign aimed at the high-speed rail public. By demonstrating the diverse set of people who could benefit from HSR, the project reminds us how personal transportation really is.

Project Statement:

To build President Barack Obama’s vision of high-speed rail corridors around the country, we will need the support of many Americans. One way to gain that support is to inform and inspire. This set of six profiles describes real situations embodied by synthesized people to help readers understand that high-speed rail is about having options in travel. Options that help people travel faster, safer, more conveniently, with less pollution, and great amenities. These profiles were created to connect with viewers, to help them become aware of values they may hold that will lead them to support and demand high-speed rail.

The profiles’ design is modular: Each profile has several elements that can be mixed and matched and organized into different media or layouts, to serve different advertising, marketing, or sharing purposes. These elements are the photo, the railroad crossing with a mini biography, a full biography, the answer to “How would this person’s life change with high-speed rail?”, and a quote that attempts to summarize that answer. We envision these elements being remixed and arranged into postcard-sized flyers, billboards, advertisements on buses, brochures or as the basis for short documentaries.

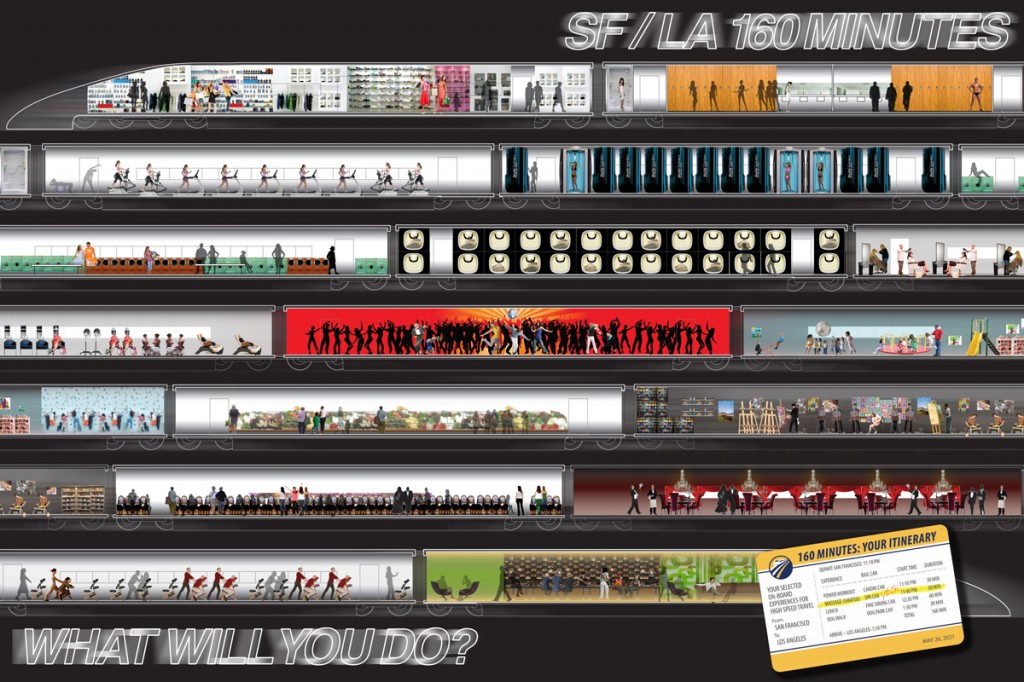

What Will You Do?

Rael San Fratello Architects

Oakland, California

Advisory Overview:

What Will You Do? choreographs how high-speed rail might combat the detrimental effects of sitting with a trip from LA to San Francisco.

Project Statement:

LA to San Francisco in 160 minutes—GREAT! But ironically, as the size of cities and the speed in which we are able to travel great distances increases, we are increasingly more sedentary. In fact, we are sitting down more than ever before—9.3 hours per day, which is more time than we spend sleeping. And the amount of time we spend sitting today increases the risks of death up to 40 percent. Instead of sitting for 160 minutes, why not create a high-speed rail that allows us to choreograph a set of experiences that make us productive, healthy and social individuals. Exercise, dance, shop, tan, eat, do laundry, play, take art classes and even sleep (ok, sometimes we need a break too!).

As we push into the 21th century, let us not fall into the traps and preconceptions of the 20th century that generated technology that supplanted our active minds and bodies. Today, obesity and diabetes are among the nation’s most pressing health issues, and they are directly related to our sedentary lifestyles. We also have no time to make selective choices about food, or even have time to do laundry because average Americans are chained to a computer working for 46 hours per week and spend more than 100 hours a year behind the wheel of a car sitting in traffic. We propose that advanced transportation infrastructure and a spirited engagement of our senses can be one. As we travel up to speeds of 220 mph, we do not need to be in park. 160 minutes—what will you do?

PROJECT TEAM: Virginia San Fratello, Ronald Rael, Emily Licht, Kent Wilson

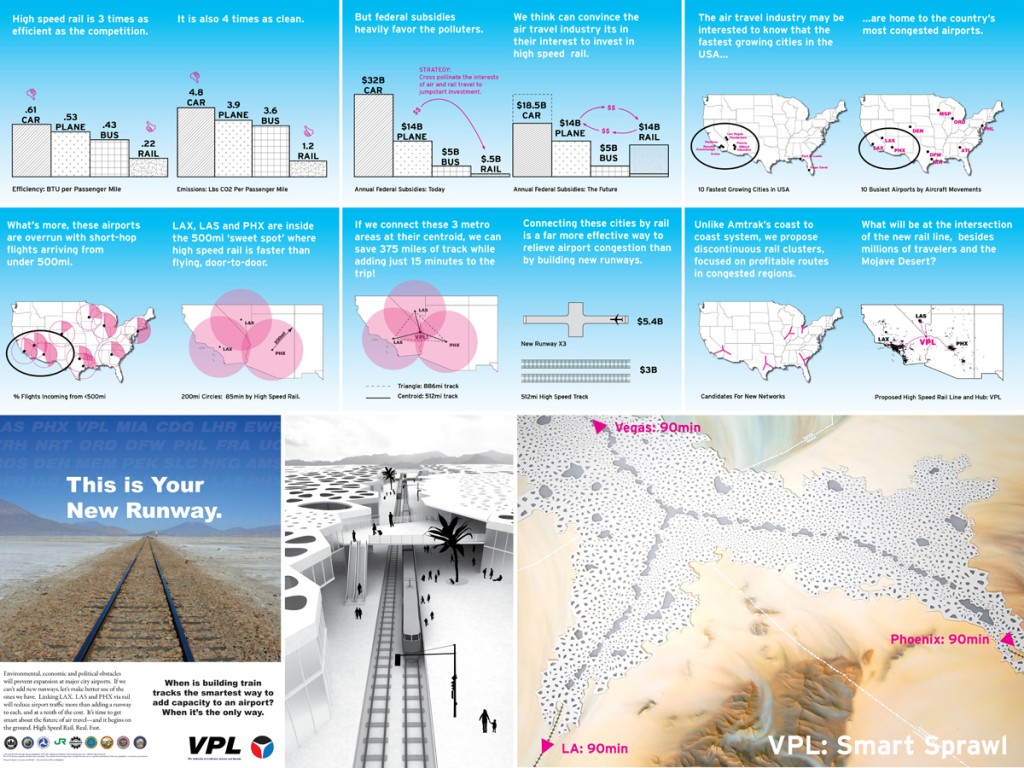

VPL

Rustam Mehta, Thom Moran

New Haven, Connecticut

Ann Arbor, Michigan

Advisory Overview:

VPL co-opts the existing transportation networks of peripheral airports in lieu of central business districts.

Project Statement:

VPL is the product of unexpected economies and partnerships resulting from hybridizing rail and air travel in a triangle of the Southwest that contains eight of America’s ten fastest growing cities and three of the nation’s most congested airports. Like other beloved American acronyms, the airport code VPL will be become the name for a vast development zone in the Mojave desert equidistant from Las Vegas McCarren (LAS), Phoenix International (PHX) and Los Angeles International (LAX). What makes VPL different from other rail schemes is that its funding will come from an unlikely ally: the air travel industry. Airlines facing a shortage of airspace and no opportunity for runway expansion will “keep their enemies closer” by using high speed rail to link airports via a central hub in the desert. In addition to freeing up runway space for more lucrative long haul flights, VPL is a massive property development scheme that recalls the invention of Las Vegas. At the center of the new rail lines will be an ultra-dense, flat,sun-lit station-city that is within commuting distance of Vegas, Phoenix and LA. This “smart sprawl” will mix the profit formulas of the airport city, casino, convention center and suburb, and thanks to its density and abundant supply of sun for lighting and electricity, it will also be paradoxically sustainable.

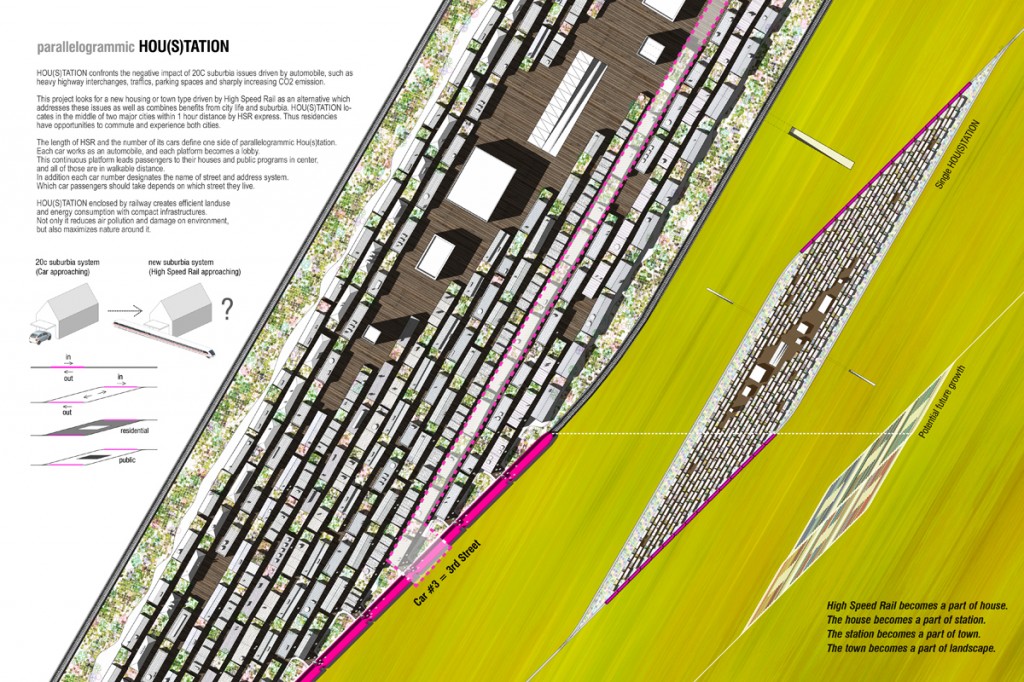

PARALLELOGRAMMIC HOU(S)TATION

SEUNGTEAK + MIJUNG

Brooklyn, New York

Advisory Overview:

HOU(S)TATION configures a new suburban morphology founded on the logics of high-speed rail.

Project Statement:

HOU(S)TATION confronts the negative impact of 20th-century suburbia issues driven by automobile, such as heavy highway interchanges, traffic, parking spaces and sharply increasing CO2 emission.

This project looks for a new housing or town type driven by high-speed rail as an alternative which addresses these issues as well as combines benefits from city life and suburbia. HOU(S)TATION is located in the middle of two major cities within one-hour distance by high-speed rail. Thus residences have opportunities to commute and experience both cities.

The length of high-speed rail and the number of its cars define one side of parallelogrammic HOU(S)TATION. Each car works as an automobile, and each platform becomes a lobby. This continuous platform leads passengers to their houses and public programs in center, and all of those are in walkable distance. In addition each car number designates the name of street and address system. Which car passengers should take depends on which street they live.

HOU(S)TATION enclosed by railway creates efficient land-use and energy consumption with compact infrastructures. It not only reduces air pollution and damage on environment, but also maximizes nature around it.

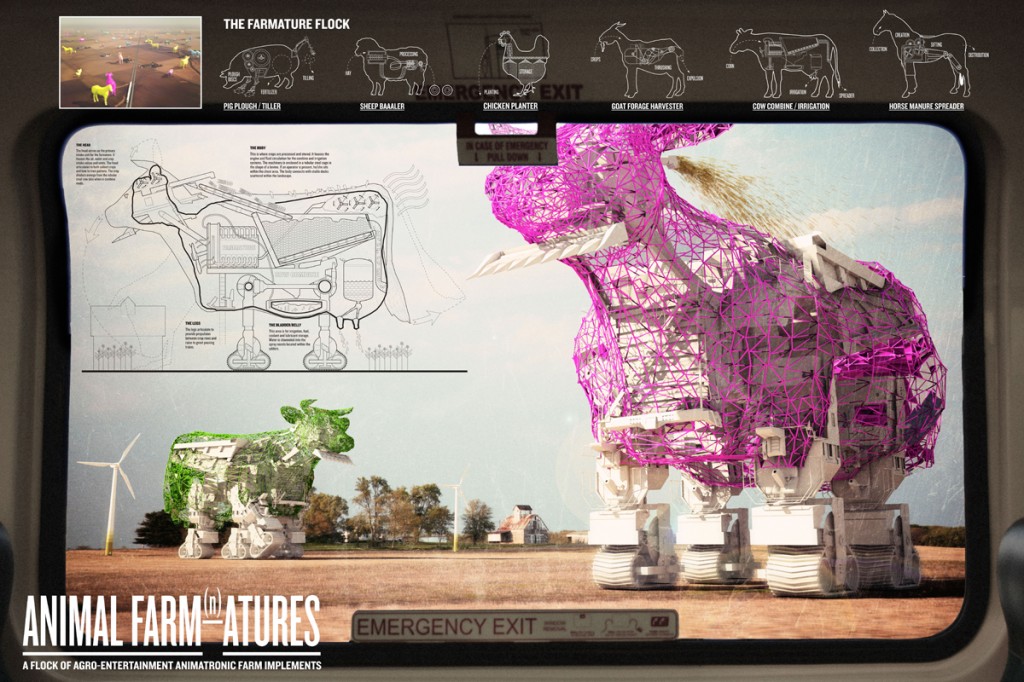

ANIMAL FARMATURES

Stewart Hicks, Allison Newmeyer (Design With Company)

Urbana, Illinois

Advisory Overview:

Animal Farmatures is a clever response to the pastoral identity of the American countryside.

Project Statement:

As a human/machine/animal hybrid, the “iron horse” locomotive captured the imagination of Americans during the middle of the 19th century by subjugating the pastoral landscape to the ingenuity of human invention. In addition to “conquering space and time,” the train was a new viewing mechanism that transformed the environment into a moving picture show through isolation, speed and framing. Today we have come full circle. Threading high-speed rail through the fabric of the American Midwest stands to recover the demand for mixing humans, commerce, technology and the rural landscape in new spectacular combinations. Which poses the question: what are the techno-natural hybrids that will capture the imagination of today’s rail riders?

Animal Farmatures are dual natured farm implements that simultaneously cultivate farmland and entertain high-speed rail customers. The animatronic appliances explore the world’s largest free-range zoological garden while digitally connected riders rush along rails through the heartland of America. Attentive audiences watch in captivity while the Farmatures complete traditional farm tasks in combination with grand rural-techno spectacles. The robotic performers extend the tradition of machines using and mimicking animals for moving, operating, branding and processing food crops while creating a majestic (re)constructed terrain of roaming beasts. They return to their docking stable for the night after a long day of foraging, weary from their performance. Stationed alongside the organic based cows, sheep and horses, the proud ringmaster farmers tend their flock and prepare them for the next crop.

TEAM MEMBERS: Stewart Hicks, Allison Newmeyer with Hugh Swiatek

Competition Announcement

President Obama’s 2011 State of the Union laid out a vision of how the United States will “win the future.”

In addition to proposals for increasing broadband access and investing in entrepreneurial innovation, the president called for a new high-speed rail network that will connect 80 percent of Americans in the next 25 years.

Two weeks later, Vice President Joe Biden announced that the government will spend $53 billion over the next six years on high-speed rail construction and passenger rail maintenance. The federal government’s position is clear: it wants high-speed rail to be a big part of the country’s 21st-century transportation infrastructure.

But what will high-speed rail (HSR) mean for Americans? While HSR has been a prominent feature of European and Asian transportation for decades, the United States currently has just one HSR line: the 150-mph Acela Express line, which runs between Boston and Washington, D.C. Although the Acela Express transports fewer than 9,000 people per day, other HSR projects around the world are much more integrated and popular. The latest HSR line in China is estimated to transport 220,000 people a day between Shanghai and Beijing — more than all the passengers that fly through the world’s busiest airport in Atlanta each day.

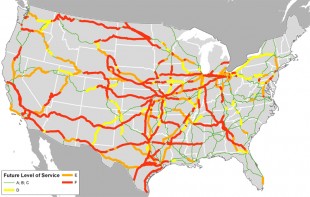

The American HSR initiative aims to increase passenger numbers, train speed and eventually build rail infrastructure in eleven megaregions around the country. But more than speed movement, HSR has a host of other impacts from shifting the identity of American transportation to reconfiguring how that transit gets funded.

Some urban planners see HSR’s potential to enhance regional planning. A new rail network, oriented around the country’s most populous regions, could revolutionize how cities are connected within regions and alter where and how people choose to live and work. By shifting demand to transit corridors, rail may curb sprawl in some areas and spark development in new areas. Skeptics claim that HSR is not the appropriate planning tool for some parts of the country, where low density and dominant car use make its popularity less likely. They remind rail advocates that HSR is not a one-size-fits-all infrastructure.

Sustainability is another national priority in the 21st century, and HSR is touted for saving millions of car trips and short-haul flights. Driving as currently practiced fails to account for externalities such as carbon emissions, congestion, dependence on foreign oil and the costly maintenance of highways. With several states facing untenable budgets, highway infrastructure reaching its obsolescence point in the coming decades, and some kind of carbon trading framework increasingly likely, these externalities are unlikely to be ignored forever. A richer rail network may emerge out of necessity, rather than choice.

But building high-speed rail isn’t cheap; in fact, some estimates show that it’s about 20 times more expensive than paving highways. HSR critics suggest that high-speed trains are economically unsustainable for the country; in Florida, Governor Rick Scott recently canceled an HSR project that would have connected Tampa with Orlando, claiming that the state could not afford to pay its portion of the rail line’s cost. Editorials published in The Washington Post and other periodicals have criticized the fact that high-speed rail requires billions in subsidies (although they often fail to compare rail subsidies to those for highways and the automobile industry). Moreover, pundits and the public alike have lamented the cost of a high-speed train ticket. The average price of a one-way ticket on the new California line is expected to be $105; as the passenger numbers on the Acela Express suggest, many people cannot afford the fastest trains. Lastly, local officials have questioned whether it makes sense to invest billions on high-speed rail rather than improve local transit projects, which would affect a greater number of people every day and ostensibly better achieve the environmental goal of getting people out of cars and on to trains.

Questions about American transportation policy will be at the forefront of politics this summer as Congress debates the long-expired federal transportation reauthorization bill — an omnibus package that sets the funding and strategy for transportation over the next six years. But while much of the conversation about HSR has been full of statistics and political ideology, it has been devoid of the design community’s input and vision. A few tired maps show where rail should be implemented, but these images fail to address the transformations that HSR could bring to social, economic, cultural and environmental contexts.

What does it mean to embark on such a transformation of American infrastructure? What will the consequences of HSR look like, in terms of cities or rural places, new trains and old ones, local economies and global connectivity? What will it mean if economic and political obstacles prevent HSR from becoming a reality? It’s the design community’s turn to synthesize and envision the impacts of this technology.

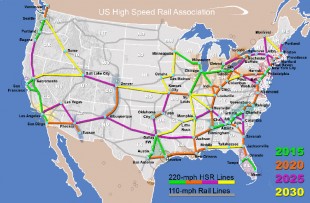

Alternate Visions

Organizations like America 2050 and the US High Speed Rail Association, among others, have put forth alternative proposals for HSR development. With different potential routes and implementation schedules, they contribute varying degrees of independent research and analysis to the discussion.

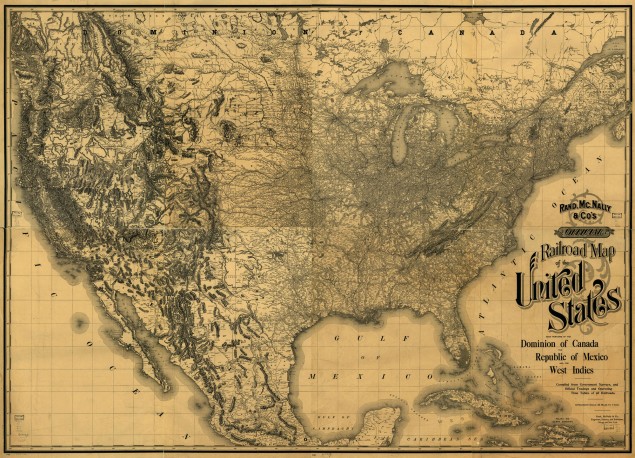

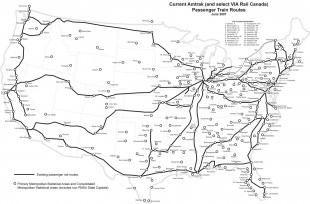

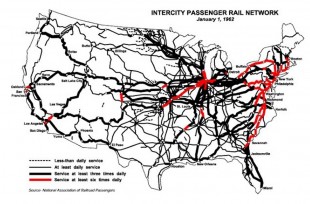

PASSENGER RAIL HISTORY

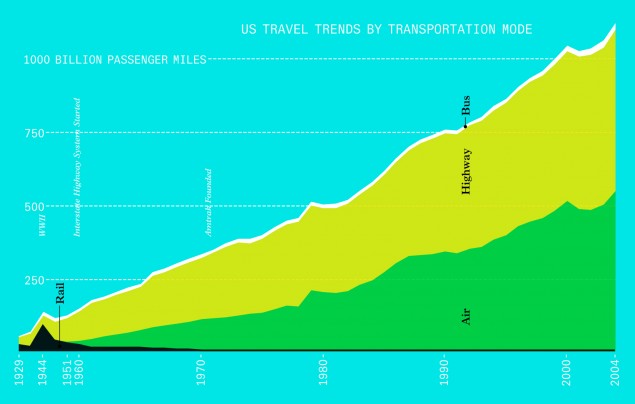

Passenger rail travel, once incredibly prevalent in the US, declined rapidly with the introduction of the Interstate Highway System. Most remaining intercity passenger rail was consolidated into Amtrak, a government owned corporation, in 1970.

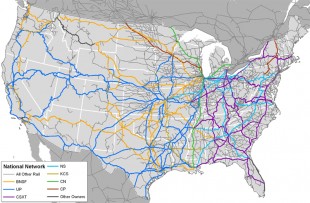

FREIGHT

Though passenger rail declined over the latter part of the 20th century, an extensive network of freight service is still in use and will surpass capacity in many areas without future upgrades. In 2009, Warren Buffett invested $26.5 billion into Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway, stating that, “over time, the movement of goods in the United States will increase, and BNSF should get its full share of the gain. The railroad will need to invest massively to bring about this growth.” Some HSR proposals make use of existing freight infrastructure and right of ways; but grade-separated, dedicated HSR track is generally necessary to reach speed thresholds of 150mpg or greater.

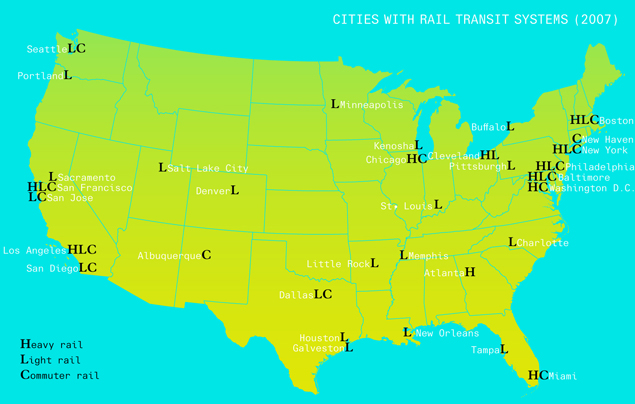

CITY TRANSIT

An occasional point of HSR criticism is the perceived lack of public transit availability upon reaching an arrival city. The indicated cities above have existing light, heavy or commuter rail systems already in place and most medium and large US cities have extensive public bus networks.

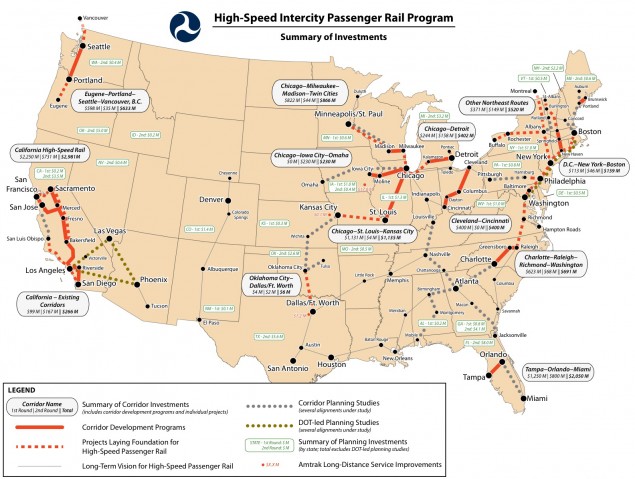

FUNDING STATUS

The current administration has called for providing convenient passenger rail service to 80 percent of Americans within 25 years. $8 billion from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and $2.5 billion from the 2010 budget have already been allocated, and Vice President Biden recently called for an additional $53 billion in funding over the next six years. The image above illustrates the status of federal investments in HSR projects as of October 2010. Subsequently, newly elected governors in Ohio, Wisconsin and Florida have rejected federal HSR funds.

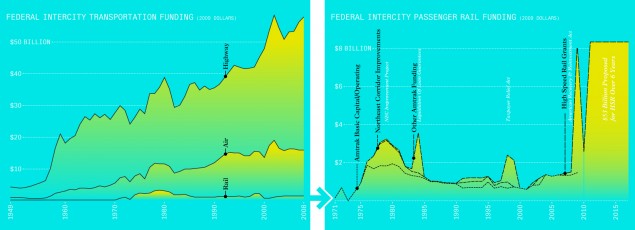

FUNDING HISTORY

Historically, the vast majority of federal funding has been focused on highway and aviation systems with just 3 percent dedicated to intercity passenger rail in the year prior to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Additionally, federal rail funds prior to 2009 have come from annual appropriations and served almost exclusively to cover Amtrak’s capital needs and operating deficits with little long-term investment into improved technology or service.

TRANSPORTATION MODES

Intercity miles traveled by automotive and airline passengers parallels federal investment trends with substantial growth observed since the 1950s.

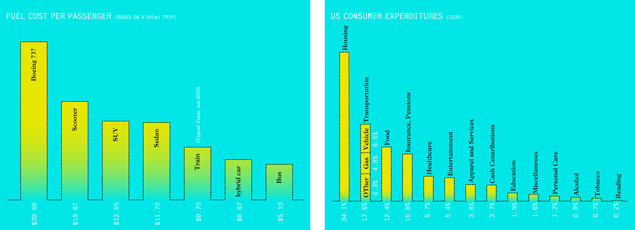

PASSENGER COSTS

All forms of transportation balance personal costs with public infrastructure investment, whether highways, airports, railways or sidewalks. And since each mode of transportation is subsidized differently, costs to the end consumer can be difficult to compare. Fuel costs for instance are typically lower per person for rail than automobiles, but such statistics seldom acknowledge that most passenger rail and virtually all high-speed rail use electricity. As the price of oil fluctuates, so does the relative cost of driving to rail travel. Such costs are important to consider as the average household spends 17.4 percent of their income on transportation, second only to housing – and nearly as much on cars alone as on food.

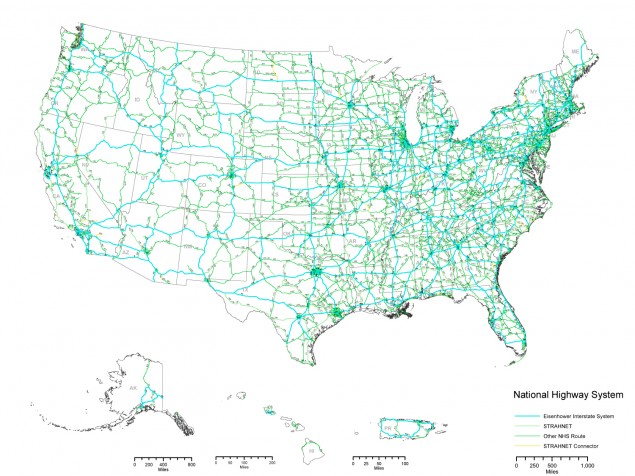

HIGHWAYS

At about 6.5 million miles, the United States has more roadways than anyone (India, second, has 3.3 million). The Interstate Highway system established under the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act of 1956 by President Eisenhower and other roadways under the National Highway system (image above) total 160,000 miles and are located within 5 miles of 90 percent of the US population.

CONGESTION

In 1982 the only city considered by the Texas Transportation Institute to be congested was Los Angeles. By 2005, 27 additional cities met such criteria. The image at left illustrates that much of the National Highway System, even on intercity routes, is anticipated to be congested during peak periods by 2035 without significant infrastructural improvements. Many suggest that the system may be reaching a critical mass and that increased capacity won’t be enough to relieve congestion. For more info, see TTI’s website (link at bottom of page).

AIRWAYS

Short-haul flights, those under 400 miles, have actually been in decline since the 1990s even while overall air travel has increased. Most of the decline is attributed to higher fares and longer pre-boarding wait times. While telecommuting may be contributing to some decline, increased demand for longer flights at a time when some airports are nearing capacity is an added source of pressure.

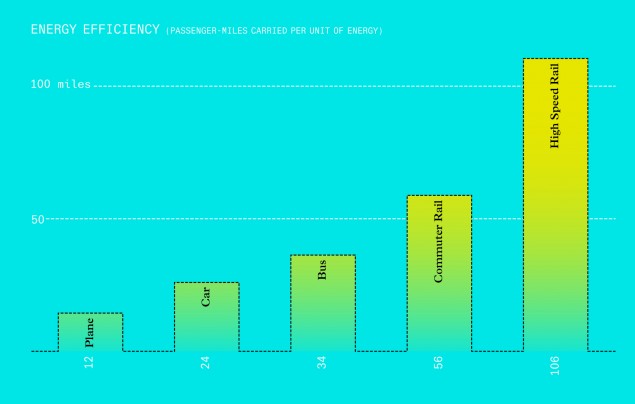

SUSTAINABILITY

On a per-passenger basis, high-speed rail is the most sustainable form of long-haul transportation in terms of energy efficiency. It uses one-third the energy of a plane ride and one-fifth the energy of a car ride. The California high-speed rail system aims to be powered by 100 percent renewable energy, reduce sprawl in the state by supporting transit-oriented development, and eliminate 12 billion pounds of CO2 emissions annually.

SOURCES

Federal Railroad Administration

US High Speed Rail Associations

America 2050

Library of Congress

National Association of Railway Passengers

Association of American Railroads

National Transit Database

US Department of Energy

US Department of Labor: Bureau of Labor Statistics

US DOT Research and Innovative Technology Administration (RITA)

US DOT Federal Highway Administration

Texas Transportation Institute

International Union of Railways

California High-Speed Rail Authority