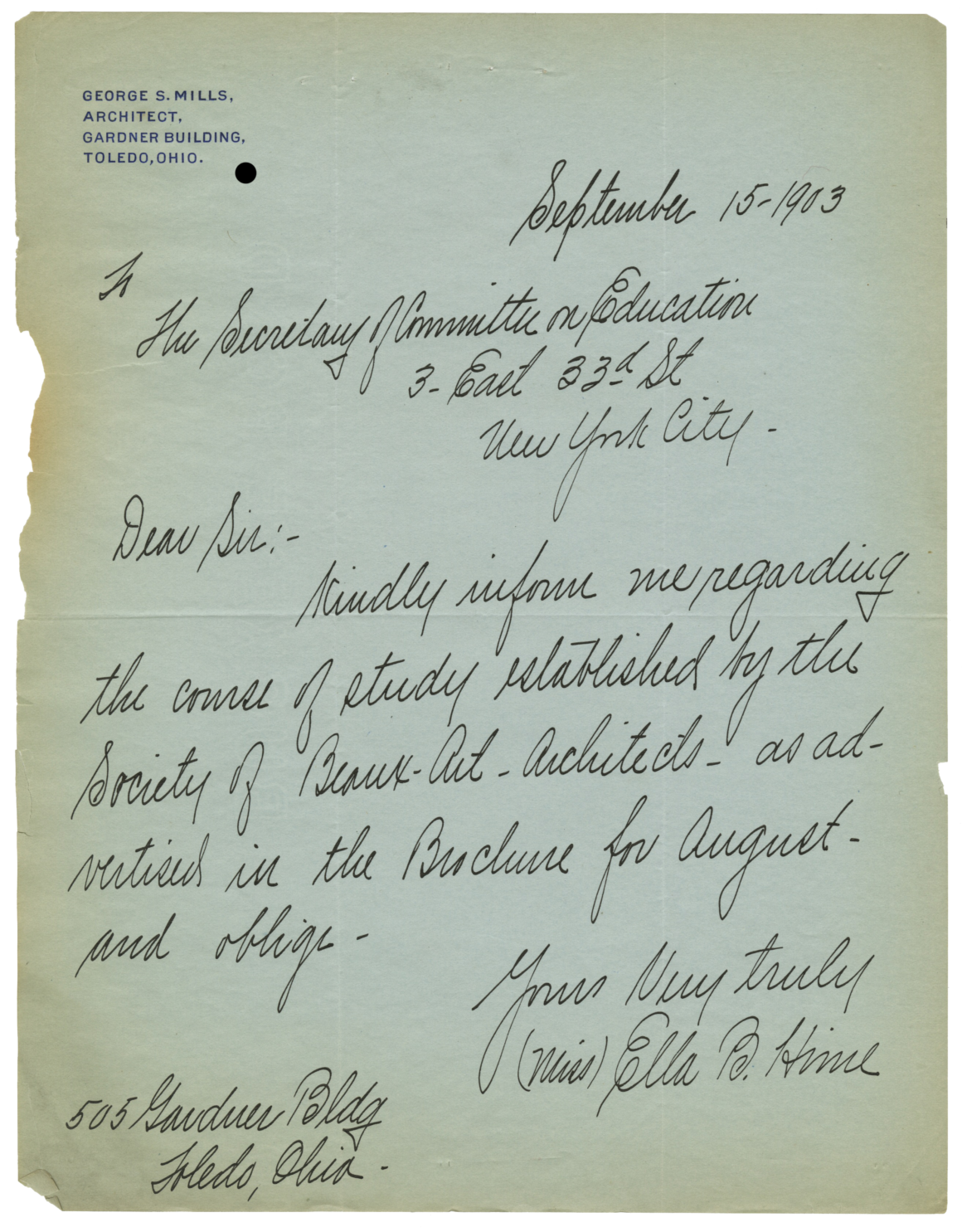

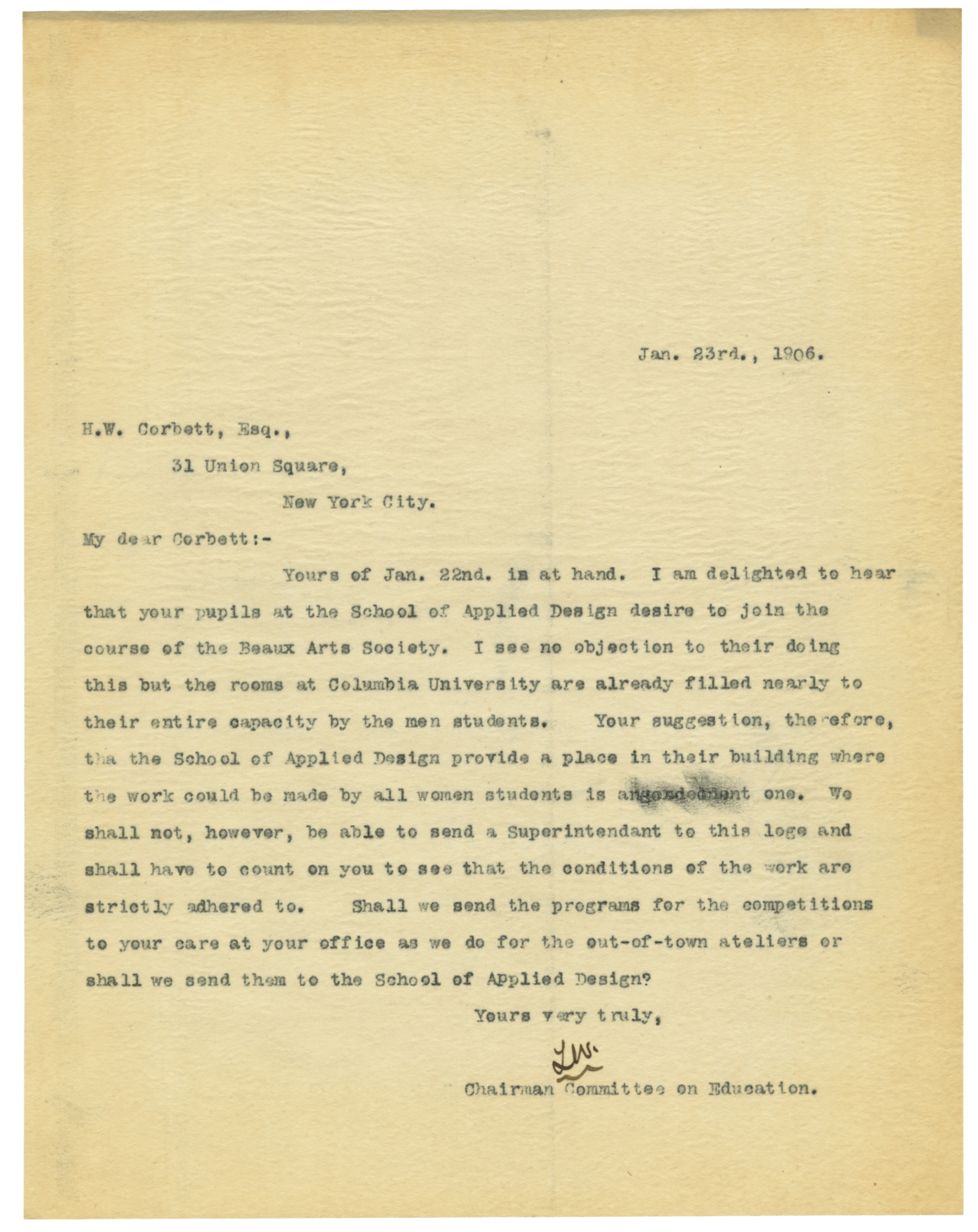

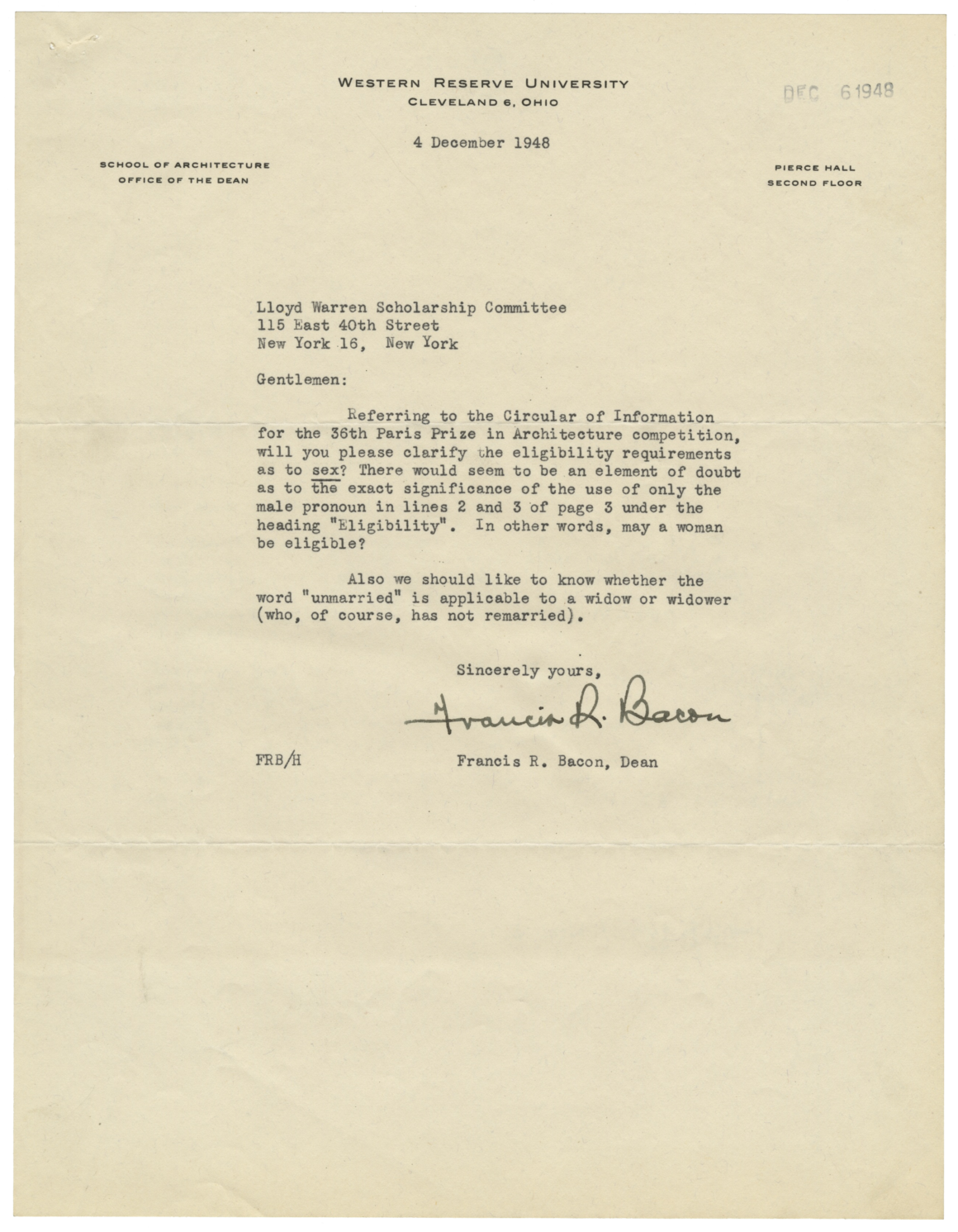

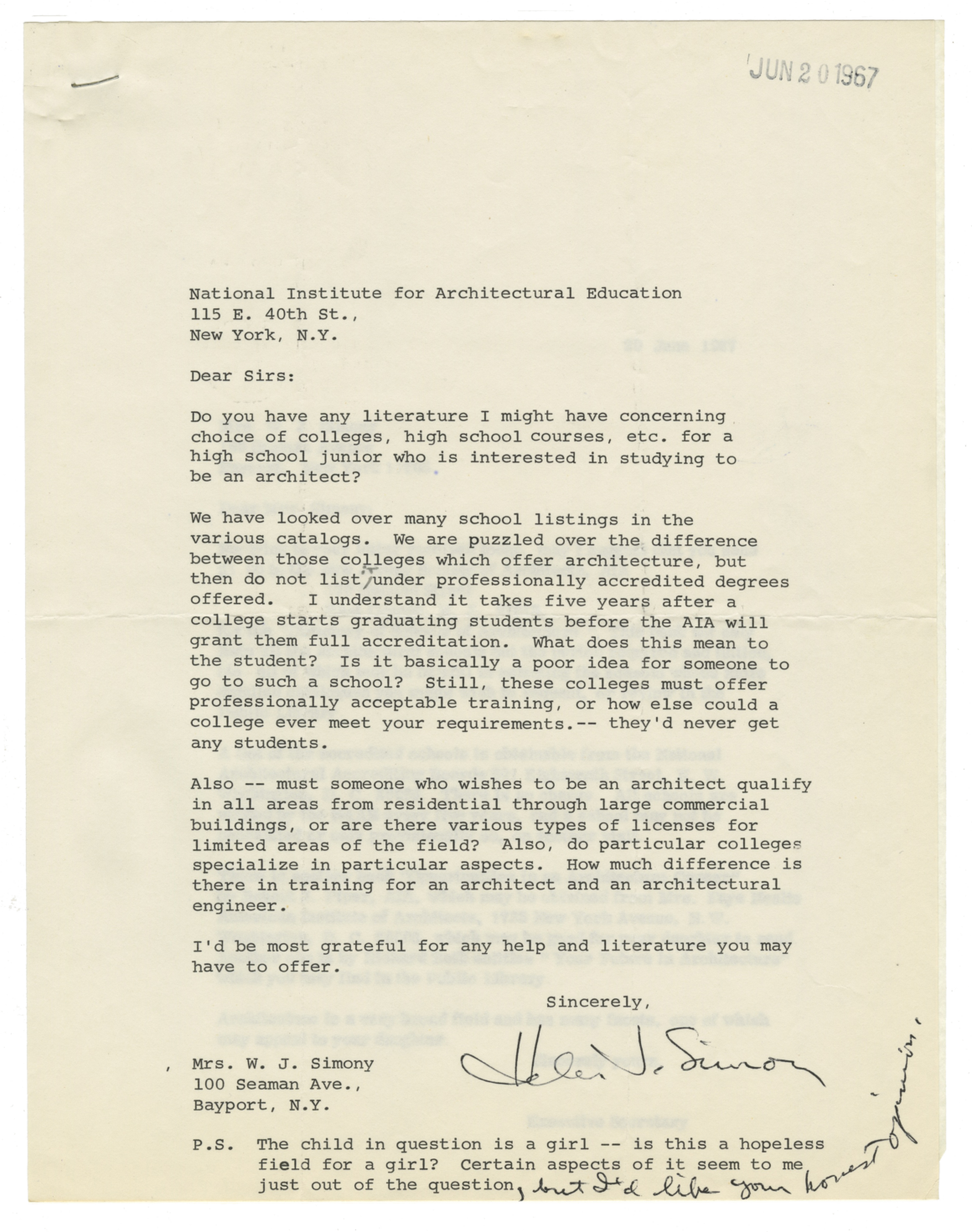

In its earliest days, the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects was unusual as an organization in that its education programs were, to all appearances, open to everyone. It was conceivable for a woman to win the Paris Prize, though it never transpired. Nevertheless, our archives unearth the women who regularly wrote in for the programs, who likely participated in ateliers in their own communities.

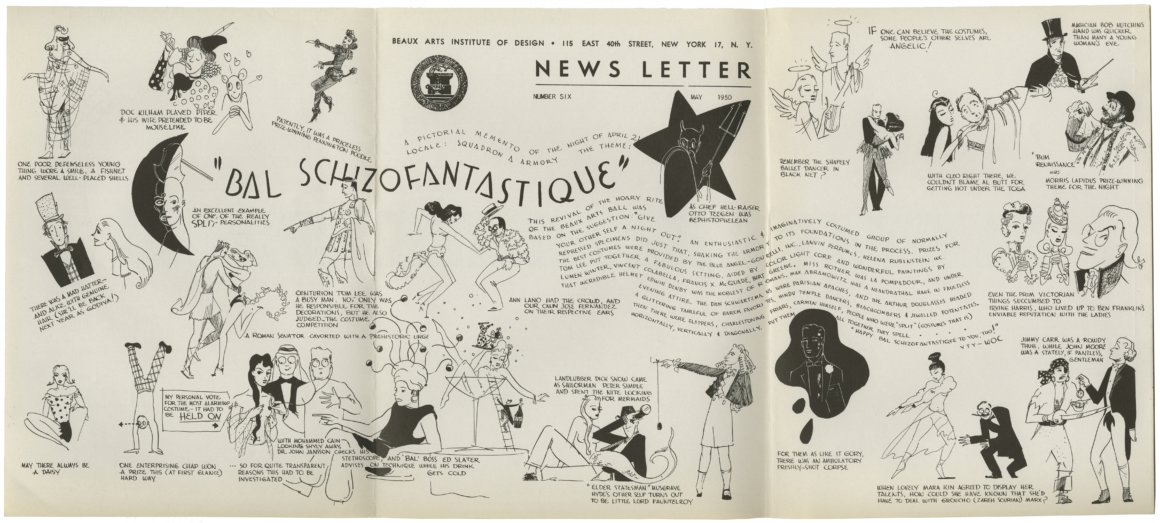

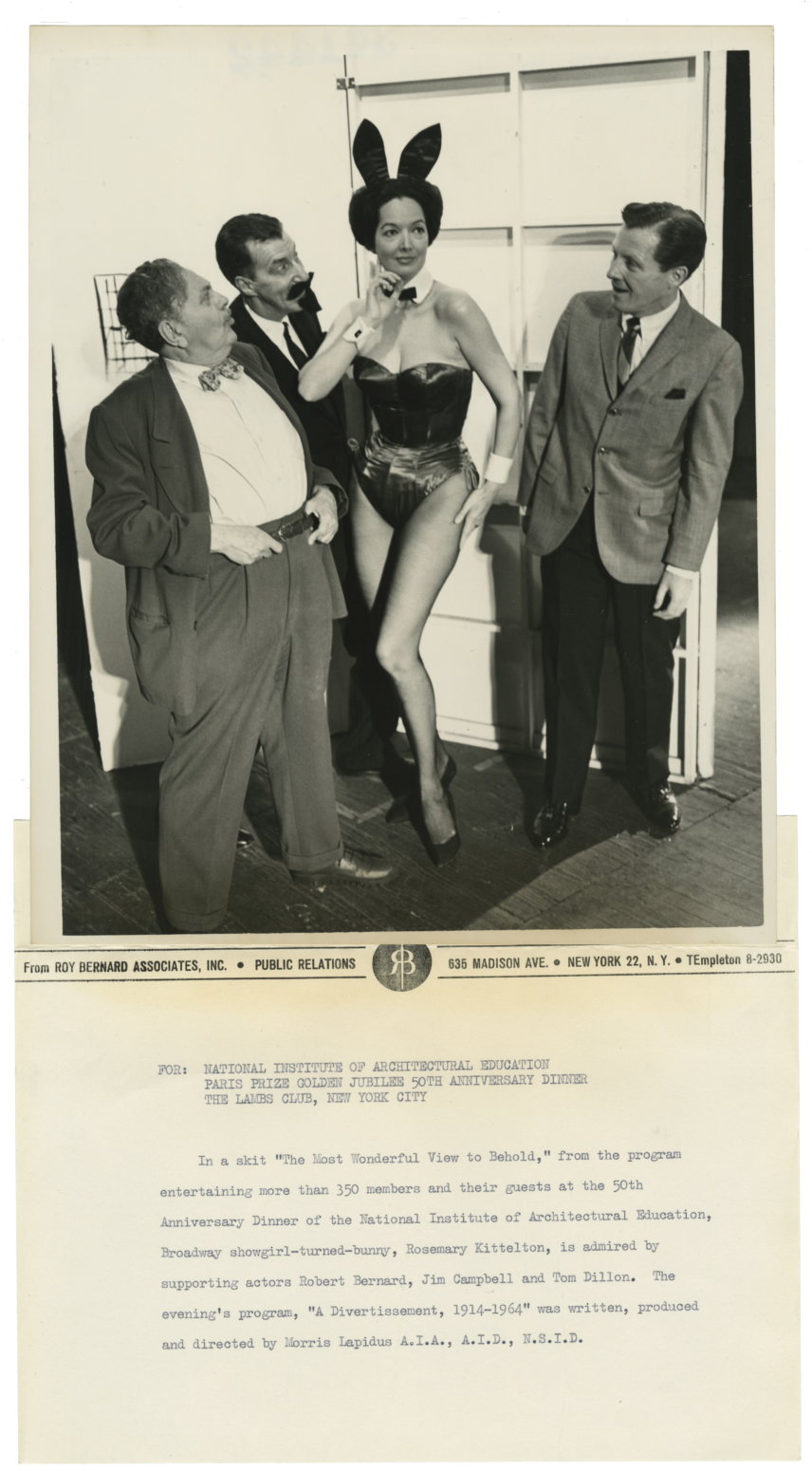

While women were few and far between in the architecture schools of the time, they pervaded the imaginations of the men who put together the Beaux-Arts Ball programs and other social events for the Institute. Lewd skits, songs, and cartoons abound the archival materials from these events.

As women made gains in the profession, the crudity of entertainment necessarily dissipated. The story of M.J. Long is an example of a female prize winner making her way as a young architect in the 1960s. By the 1990s, the scales had tipped so that the list of prizewinners nearly split between men and women.